SATURDAY, MAY 21, 2016: NOTE TO FILE

The Tairona

An introduction to a possible history

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS:KOGI, TAIRONA, FROM THE WIRES, SUSTAINER CULTURE

Abstract: We actually know very little about a people we should know more about. Based on what is known, a possible history suggests why we should learn more about and from these people of place.

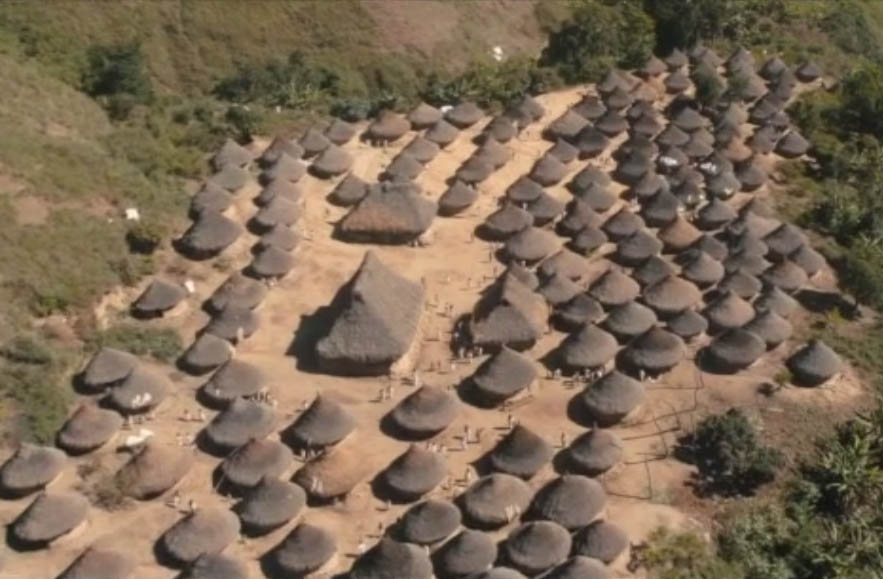

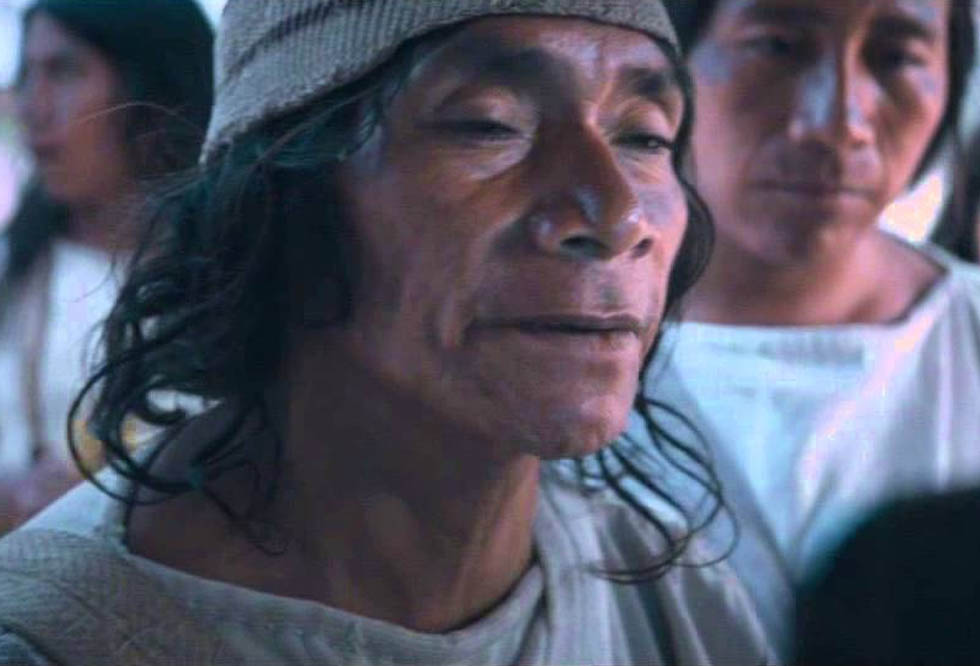

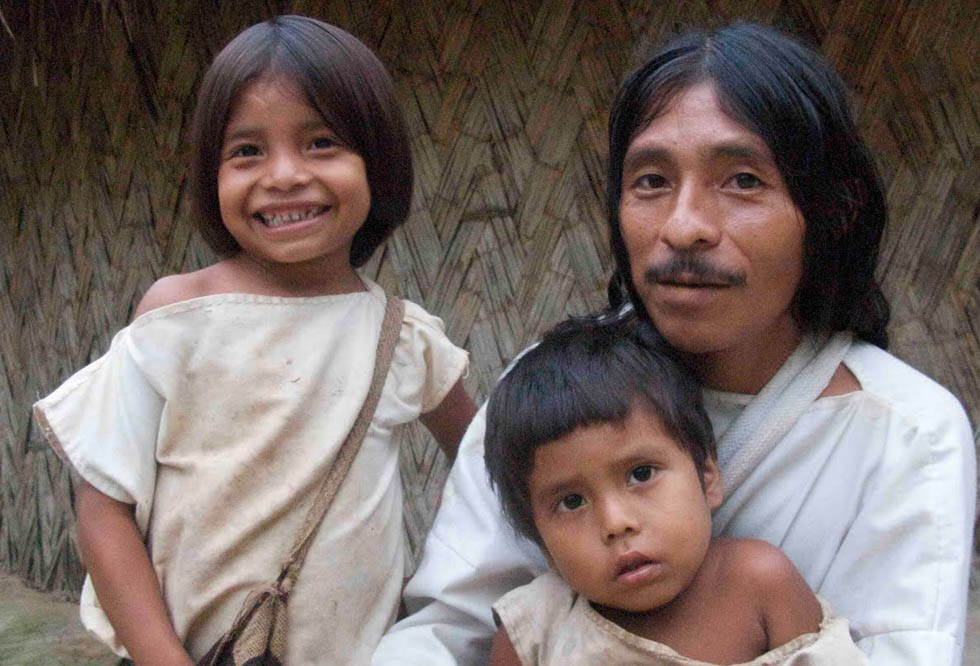

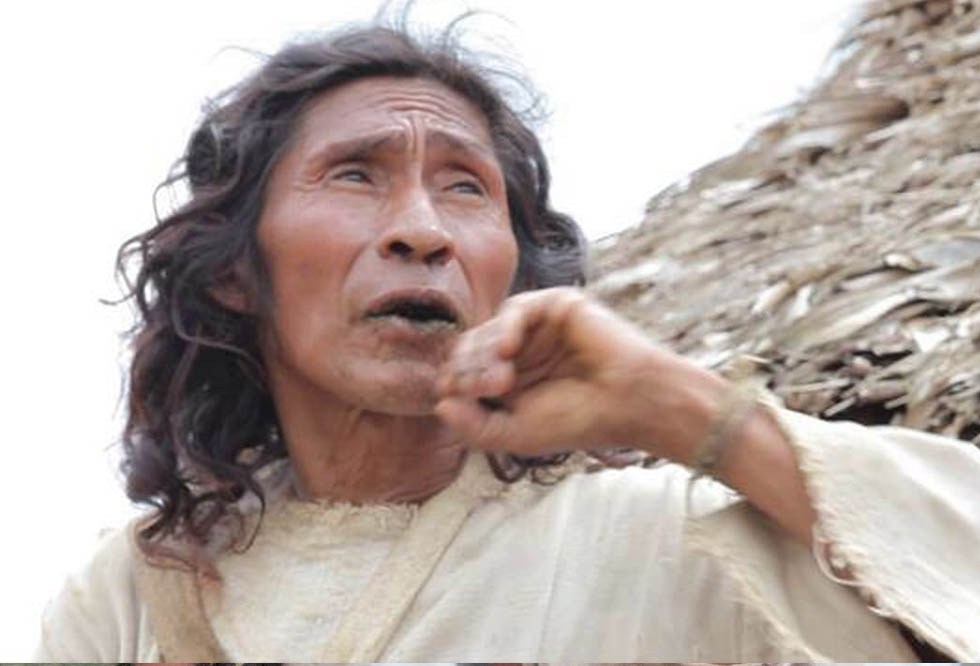

TUCSON (A-P) — The Tairona, a Pre-Columbian civilization in the region of NE Colombia who traded with the Aztecs and Maya, have a story, or rather multiple stories are told about them. It is a story as pieced together from archaeology, chronicles, and oral history that varies with the storyteller. Scientists (e.g. archaeologists), historians and other scholars endeavor to tell the most likely story. The following is based on the stories others tell, but is not limited to "just the facts" known without noting implied human ecology context about this one people and their civilization. A strict telling is limiting and may lead to a story that falls short of being the most likely. Drawing upon all that is known about all civilizations and their peoples, and using it to flesh out the skeletal knowledge we have of the Tairona, will be more instructive. Any story of the past is an imaginative reconstruction based, at best, on evidence. Stories of the future are stories of possible futures based on the past with no archaeological record as evidence to guide the storyteller. To avoid qualifying every statement and referencing every claim, the following story is didactic and may be dismissed a pure fiction, but it is a likely story told as if the storyteller was privy to all. That stylistic pretense is fiction, but the story is otherwise intended to be a "likely" story. First, let's tell a tale of a civilization that did not end up building monuments to elite interests nor commit empire on a grand scale ending in the obligatory fall or conquest from without. They did not build massive pyramids, build palaces for the elites, nor wage war on neighbors. Movies are not made about them. There is no veni, vidi, vici. We of the global Euro-Sino Empire of fossil-fueled growth, exploitation, and planetary destruction cannot take much interest in the Tairona and their contrarian ways. Indeed, we may be programmed from birth to be unable to understand them. A remnant population of Tairona civilization, the Kogi, did survive into the 21st century. They have spoken to warn Younger Brother, and few young'uns have been able to listen and fewer have learned from them. They are as apostates to the growth culture of consumers without borders. They are heretical unbelievers who do not believe in belief, who do not advocate for "MORE!". They focus on the world before them and understand and use metaphor to speak of things that have no name. They point to the what-is. The believing minds of Younger Brother would rather believe than know, and so fail to see what is in front of their face even when the mámas rub their noses in it.

Younger Brother Mámas have "ideas about the structure and functioning of the Universe," called science. We also need to maintain a viable equilibrium between "Man's demands and Nature's resources." This is Ecolacy 101 of which few Younger Brothers know anything, let alone enough to mold human behavior into a plan of action and avoidance. The mámas of the world need to unite, to work together so we and the world as we know it does not die.

Tairona Timeline

The Tairona phase 1 story is one of empire-building-as-usual, of chieftainships competing, bigger fish swallows little fish, agricultural surplus supports warriors, wealth is accumulated and aristocrats demand ever more from increasingly distant commoners as empire expands. At some point, commoners cannot produce ever more, even under threat of force, and the system breaks down. Empire falls, either to be conquered from without or slowly recover, typically to repeat the pattern. Tairona phase 2 offers a twist to the usual story. Priests bite the hand that feeds them, their co-lords with their warrior minions, and came to dominate them with the support of the commoners, who were near revolt, as is possible when elites are weakened by material descent. The Taironans were subject to being raided by the more war-like Carib Indians who would come Viking-like to raid coastal villages. The warrior class was replaced or reeducated to become community guardians. They maintained an ever watchful presence and if invaded, at the first sign, a call was put out to neighboring communities to send their guardians along with all available commoners, men and women, to come and form a wall of humanity. A few canoes of a few dozen warriors, confronted by an organized mass of thousands, had no other option but to flee, even if the thousands were merely armed with sticks and stones. The chief of each small community of 20 to 50 people came to be appointed by the priests as were the guardians who replaced the warriors. Neither chief, guardians, nor priests lived in bigger or better houses than the commoners or consumed more stuff. The priests directed the chief to organize the people to do needed public works projects, such as to maintain the roads. Prosperity grew and it all looked deliriously good as the economy grew. The priests, however, were too focused on serving the people and being popular, on enabling growth and development. They neglected the environment even though they "knew" or thought they knew that they were the environment. But it turns out they really didn't know the environment, merely believed they did, and there were consequences. Tairona phase 3 began when the priestly empire of belief faltered, when the promised ever-growing-prosperity failed and growth transitioned into descent, into hard times. The credibility of the priests, in the commoner's mind, was discredited by their failed promises. The Empire of Belief ended when the people stopped believing in it. The intellectual class that had mostly been ignored by both priests and commoners had long seen through the confabulations of the priests and had foreseen a bad outcome to priestly humancentric economic rule. They had warned the priests and commoners, but had been ignored until the Empire of Belief could no longer be believed in. The ones who would rather know than believe staged a coup and ousted the true believers. The intellectual class found much to admire in the priests, as compared to the aristocratic lords who lived by force or threats, but they showed no restraint in cleaning house, in disposing of bad ideas. The commoners saw them as the new priests, called mámas. They retained the priestly lifestyle, wore the same clothes as the commoners, ate the same food, slept in a hammock like everyone else, and lived in houses just big enough. Their material possessions fit in two bags that were carried under each arm. The idea of using their elite status for self-gain was either unknown or dismissed as aberrant as 18 years of education had made clear. The mámas had been paying attention and had learned the hard lessons as taught by the Universe (the Mother). It had to be system over self. We all are the environment, Aluna, and we must serve our life-support system or suffer a ghastly future. The suffering had been horrible and the mámas saw this as indicating a human failure to moderate human demands on Aluna's resources. It was their task to help the commoners live right and well within limits to achieve a sustainable prosperity. They studied hard, and thought and thought and thought about how best to do so. Their guidance mostly worked and improved as the centuries passed. The commoners respected them accordingly. They willingly sought their advice and accepted limits. The mámas were elites and they ruled by consensus among themselves (their society was not democratic). Some mámas merited greater respect from the other mámas and so were somewhat more elite. The empire of the mámas was an Empire of Respect as merited. They ruled the commoners by merit, by listening to Aluna who has all the answers. The consensus of the mámas was their best guess as to what would work. The Tairona were ruled by a meritocracy, and thereby thrived in moderation within limits. Their civilization did not grow, did not expand, did not conquer new lands, but all had enough and the centuries passed. Enough was enough. Education of mámas: First nine years, students are selected from birth to about 5 years of age and children in training live in a cave or closed to daylight structure with contact by the mother and máma teachers. During early adolescence/puberty students are given a break from training to explore the world outside. Student or teacher may decide to discontinue their training at this time. Those continuing training receive another nine years of intensive study, that includes mindfulness practice, before becoming mámas and working to serve the environment (Aluna) and community (in that order). They do not do physical labor. Females, though fewer in number at present, are also educated to become mámas. Women are by nature attuned to Aluna and do not require the special education and coca leaf chewing practice to aline themselves with the Great Mother as do the men (due to atavistic dominance/aggression alpha male issues). The mámas, like all organisms, want to maximize prosperity (empower) for all. But they thought about it. Some years were better than others, but even in a bad year humans should have enough of what they need. There will always a 100-year bad-year, a 500-year bad-year, and a 1,000-year bad-year not to mention bad-decade or century. Even in the 1,000-year bad-decade, environmental reserves must be such that the people never end up eating each other. Almost every year would be a year of prosperity such that more growth in human numbers and per capita consumption could be supported. Normal humans are clever apes who can and will maximize growth. The mámas had learned from Aluna (as their K-strategist ancestors had) that to live in prosperity over the centuries, one had to willingly live within limits or have limits imposed from without via die-off. Really clever apes could learn to live within limits to maximize empower over the long view of time. Mámas realized that all humans should have enough but no more. If what is needed to live well—a healthy, loving and productive life—is 1x, but the people demand 10x, then the environment can either support 10,000 humans at 1x or 1,000 humans at 10x. To consume 10 times more than actually needed was unethical, was to deny a healthy, loving and productive life to 9,000 human Earth Guardians. So the mámas studied life and thought and thought and thought about what was enough as distinct from what was wanted. Enough food, enough nutrition, enough water, enough shelter, enough clothing, enough health care, enough personal possessions. They guessed then tested; evaluated results, and guessed again. In a few centuries they had a good grasp of what humans really needed. The carrying capacity of Aluna was assessed, by guess then test, and máma knowledge grew asymptotically without limit. Material growth was limited, but love and understanding need not be constrained. Mámas even love Younger Brother. The mámas married and had children, but no more than did commoners. Young mámas accepted guidance in taking a mate and in having children. The commoners married with a máma's blessing and a máma's blessing (a Mother's or female máma) was required to have children that the community would take in as a new citizen. Certain changes in custom were needed and some seemed radical to those who had to change their ways, change what they had been conditioned from birth to believe to be natural and normal. The greatest challenge the mámas had was, while favoring prosperity for all at all times in terms of each having enough, to limit the natural and normal response to prosperity of population growth. The cold equations could not be ignored. The mámas had to assess the environmental carrying capacity for a given level of per capita consumption of renewable resources. Theirs was the best possible guess and determined the total population for an area while still allowing for the 1,000-year bad-decade which could be endured with some suffering but not die-off. If the population was at the limit, the mámas blessings were equal to the death rate. If the region is assessed to be underpopulated, the blessings are more freely given, and if overpopulated, blessings are fewer. So far, what was needed was clear. The detail of how to avoid unblessed births, was not. The mámas had to think and think and think, and guess then test. They learned to do the hard thing. The changes in custom that worked: Marriage also required a blessing. The young were helped "to think about it." Marriage based on infatuatory sexual feelings was discouraged as the mámas had noted them to be unstable with "true love" turning too easily into false hate within a few years. Marrying after thinking about it came to be accepted. Marrying and coming to love one another ever more as the years passed became normal again, as was divorce should there be irreconcilable differences. Mámas do not pretend to know all. At best they guess well then test and learn. To avoid unblessed pregnancies required sex education. If unplanned, an attempt was made to terminate a pregnancy. Ways to do so posed a risk to the woman and often failed. Allowing a pregnancy to go full term was also a risk. If an infant was born unblessed, a máma had to do the hard thing. Neither the mother nor father were ever punished. Their failure to practice safe sex was punishment enough. Whenever any couple failed, all would redouble their efforts to practice safe sex. One innovation was that couples came to never have sex indoors. Women and children lived in one house while the men of the family live in another close by. Couples would meet up and go to the fields at night to consecrate their love under the full view of Aluna. Couples were free to make love, but a meet up in the fields involved some forethought and planning, thus minimizing the unintended. Because underpopulation under prosperous conditions was not a problem, individuals who chose not to marry and live celibate lives were honored. Homosexuality was not merely permitted, it was celebrated. Gay couples were the primary teachers of heterosexuals on how to love one another while still having safe sex. Those not having a vagina between them taught the young men how to make love without penetrating their lover's vagina. Lesbian couples taught the young men how to pleasure a lover without even having a penis. Heterosexuals depended on the guidance of their gay brothers and sisters. The women needed far less sex education. Female mámas taught the girls about the more sexually driven boys and how to take care of them - easy when you know how. Women must demand respect, and an unblessed ejaculation in or on the vagina was to show disrespect. Young men who did not yet know how to pleasure their lover where given lessons by her or, if that failed, told to seek out a gay couple to reeducate and inspire them. If being with child was blessed, then couples could have vaginal intercourse incessantly, and typically did, before and after birth until a máma judges the nursing mother to be fertile again. There were issues. Mámas dealt with them. Rarely an infant was put to death and all redoubled their efforts to take care. As a result, phase 3 of Tairona civilization lasted 750 years without overshoot and descent, without a collapse of civilization. The lowland Tairona civilization ended, not because they celebrated homosexuality or practiced infanticide (rarely and humanely of course), but because Younger Brother, with attack dogs and guns, committed genocide.

Kogi Timeline

|

|