1976

Training for the Priesthood among the Kogi of Colombia

Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff

in Wilbert J. (ed.) Enculturation in Latin America - an anthology. UCLA 1976

[additions in brackets]

The Kogi of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in northeastern Colombia are a small tribe [in current parlance a complex society, remnant of Tairna state level civilization, well above tribal or chiefdom level in complexity] of some 6,000 Chibeha-speaking Indians [BBC documentaries mention 10 to 20 thousand Kogi], currently maybe 5k-6k. There are three other groups of remnant Tairna who have largely been acculturated into the monetary economy/culture; the Kogi population could not have grown nor be growing as Creoles push into their homeland], descendants of the ancient Tairona who, at the time of the Spanish conquest, had reached a relatively high development among the aboriginal peoples of Colombia. The Sierra Nevada, with its barren, highly dissected slopes, steep and roadless, presents a difficult terrain for Creole settlement and, owing to the harshness and poor soils of their habitat, the Kogi have been able to preserve, to a quite remarkable degree, their traditional way of life.

The Kogi of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in northeastern Colombia are a small tribe [in current parlance a complex society, remnant of Tairna state level civilization, well above tribal or chiefdom level in complexity] of some 6,000 Chibeha-speaking Indians [BBC documentaries mention 10 to 20 thousand Kogi], currently maybe 5k-6k. There are three other groups of remnant Tairna who have largely been acculturated into the monetary economy/culture; the Kogi population could not have grown nor be growing as Creoles push into their homeland], descendants of the ancient Tairona who, at the time of the Spanish conquest, had reached a relatively high development among the aboriginal peoples of Colombia. The Sierra Nevada, with its barren, highly dissected slopes, steep and roadless, presents a difficult terrain for Creole settlement and, owing to the harshness and poor soils of their habitat, the Kogi have been able to preserve, to a quite remarkable degree, their traditional way of life.

A Kogi village occupied on occasion only.

The present tribal territory lies at an altitude of between 1,500 and 2,000 meters [4,900 and 6,500 feet, but currently as low as 300 meters in places], where the Indians occupy several small villages of about ten to several dozen round huts, each of about 3 to 4 meters [10 to 13 feet, or 76 to 133 sq. ft.] in diameter and built of wattle and daub covered with a conical thatched roof. Each house is inhabited by one nuclear family composed of four or five people [1.8 to 2.5 meters square per person — 19 to 27 sq. ft./person] who sleep, cook, and eat in this narrow, dark space that they share with their dogs and with most of their material belongings. The huts of a village cluster around a larger, well-built house, also round in its ground plan, but provided with a wall of densely plaited canes; this is the ceremonial house, the temple, access to which is restricted to the men, and where women and children are not allowed to enter. Kogi villages are not permanently occupied; most Indians live in isolated homesteads dispersed over the mountain slopes, and the villages are hardly more than convenient gathering places where the inhabitants of a valley or of a certain restricted area can come together occasionally to exchange news, discuss community matters, discharge themselves of some minor ritual obligations, or trade with the visiting Creole peasants. When staying in the village, the men usually spend the night in the ceremonial house where they talk, sing, or simply listen to the conversation of the older men. As traditional patterns of family life demand that men and women live in not too close an association and collaborate in rigidly prescribed ways in the daily task of making a living, most Kogi families, when staying in their fields, occupy two neighboring huts, one inhabited by the man while the other hut serves as a kitchen and storeroom, and is occupied by his wife and children.

The economic basis of Kogi culture consists of small garden plots where sweet manioc, maize, plantains, cucurbits, beans, and some fruit trees are grown. A few domestic animals such as chicken, pigs, or, rarely, some cattle, are kept only to be sold or exchanged to the Creoles for bush knives, iron pots, and salt. Some Kogi make cakes of raw sugar for trading. Because of the lack of adequate soils, the food resources of one altitudinal level are often insufficient, and many families own several small gardens and temporary shelters at different altitudes, moving between the cold highlands and the temperate valleys in a dreary continuous quest for some harvestable food. Although the starchy tubers provide a fairly permanent food supply, protein sources are few, and a chronic state of malnutrition seems to be the rule. Slash-and-burn agriculture is heavy work, and the harsh, mountainous environment makes transportation a laborious task. Much agricultural work is done by women and children who collaborate with the men in clearing and burning the fields.

The objects of material culture are coarse and simple, and generally are quite devoid of ornamentation. Some heavy wooden benches, a pair of old string hammocks, smoke-blackened cooking vessels and gourd containers, and a few baskets and carrying bags are about all an average family owns. It is evident then that, to the casual observer, Kogi culture gives the impression of deject poverty, and the disheveled and sullen countenance of the Indian adds to this image of misery and neglect. Indeed, if judged by their external appearance and their austere and withdrawn manner, one would easily come to the conclusion that by all standards of cultural evolution these Indians are a sorry lot.

But nothing could be more misleading than appearances. Behind the drab facade of penury, the Kogi lead a rich spiritual life in which the ancient traditions are being kept alive and furnish the individual and his society with guiding values that not only make bearable the arduous conditions of physical survival, but make them appear almost unimportant if measured against the profound spiritual satisfactions offered by religion. After days and weeks of hunger and work, of ill health and the dreary round of daily tasks, one will suddenly be taken into the presence of a scene, maybe a dance, a song, or some private ritual action that, quite unexpectedly, offers a momentary glimpse into the depths of a very ancient, very elaborate culture. And stronger still becomes this impression in the presence of a priest or an elder who, when speaking of these spiritual dimensions, reveals before his listeners this coherent system of beliefs which is the Kogi world view.

Traditional Kogi religion is closely related to Kogi ideas about the structure and functioning of the Universe, and Kogi cosmology is, in essence, a model for survival in that it molds individual behavior into a essence, a model for survival in that it molds individual behavior into a plan of actions or avoidances that are oriented toward the maintenance of a viable equilibrium between Man's demands and Nature's resources. In this manner the individual and society at large must both carry the burden of great responsibilities which, in the Kogi view, extend not only to their own society but to the whole of mankind.

The central personification of Kogi religion is the Mother-Goddess. It was she who, in the beginning of time, created the cosmic egg, encompassed between the seven points of reference: North, South, East, West, Zenith, Nadir, and Center, and stratified into nine horizontal layers, the nine 'worlds,' the fifth and middlemost of which is ours. They embody the nine daughters of the goddess, each one conceived as a certain type of agricultural land, ranging from pale, barren sand to the black and fertile soil that nourishes mankind. The seven points of reference within which the Cosmos is contained are associated or identified with innumerable mythical beings, animals, plants, mineral, colors, winds, and many highly abstract concepts, some of them arranged into a scale of values, while others are of a more ambivalent nature. The four cardinal directions are under the control of four mythical culture heroes who are also the ancestors of the four primary segments of Kogi society, all four of them Sons of the Mother-Goddess and, similarly, they are associated with certain pairs of animals that exemplify the basic marriage rules. The organizing concept of social structure consists of a system of patrilines and matrilines in which descent is reckoned from father to son and from mother to daughter, and a relationship of complementary opposites is modeled after the relationship between certain animal species. The North is associated with the marsupial and his spouse the armadillo; the South with the puma and his spouse the deer; the East with the jaguar and his spouse the peccary; and the West with the eagle and his spouse the snake. In other words, the ancestral couples form antagonistic pairs in which the "male" animal (marsupial, puma, jaguar, eagle) feeds on the "female" animal (armadillo, deer, peccary, snake) and marriage rules prescribe that the members of a certain patriline must marry women whose matriline is associated with an animal that is the natural prey of the man's animal. The equivalence of food and sex is very characteristic of Kogi thought and is essential for an understanding of religious symbolism in myth and ritual. Moreover, each patriline or matriline has many magical attributes and privileges that together with their respective mythical origins, genealogies, and precise ceremonial functions, form a very elaborate body of rules and relationships.

The macrocosmic structure repeats itself in innumerable aspects of Kogi culture. Each mountain peak of the Sierra Nevada is seen as a "world," a house, an abode, peopled by spirit-beings and enclosed within a fixed set of points of reference: a top, a center, a door. All ceremonial houses contain four circular, stepped, wooden shelves on the inside of their conical roofs, representing the different cosmic layers, and it is thought that this structure is repeated in reverse underground, the house being thus an exact reproduction of the Universe, up to the point where its center becomes the "center of the world." Moreover, the cosmic egg is conceived as a divine uterus, the womb of the Mother-Goddess, and so, in a descending scale, our earth is conceived as a uterus, the Sierra Nevada is a uterus, and so is every mountain, house, cave, carrying bag, and indeed, every tomb. The land is conceived as a huge female body that nourishes and protects, and each topographic feature of it corresponds to an inclusive category of anatomical detail of this vast mother-image. The large roof apexes of the major ceremonial houses, constructed in the shape of an open, upturned umbrella, represent the sexual organ of the Mother-Goddess and offerings are deposited there representing a concept of fertilization.

The Kogi conceive the world in terms of a dualistic scheme that expresses itself on many different levels. On the level of the individual as a biological being, it is the human body that provides the model for one set of opposed but complementary principles, manifest in the apparent bilateral symmetry of the body and the distinction between male and female organisms. On the level of society, the existence of groups of opposed but complementary segments is postulated, based on the mythical precedency and controlled by the principles of exogamy. The villages themselves are often divided into two parts and a divisory line, invisible but known to all, separates the village into two sections. The ceremonial houses are imagined as being bisected into a "right side" and a "left side," by a line running diametrically between the two doors that are located at opposite points of the circular building, and each half of the structure has its own central post, one male and another female. On a cosmic level, the same principle divides the Universe into two sides, the division being marked by the tropical sun, which, going overhead, separates the world into a right and a left half. The dualistic elaborations of this type are innumerable: male/female, man/woman, right/left, heat/cold, light/dark, above/below, and the like, and they are furthermore associated with certain categories of animals, plants, and minerals; with colors, winds, diseases, and, of course, with the principles of Good and Evil. Many of these dualistic manifestations have the character of symbolic antagonists that share a common essence; just as the tribal deities who, in one divine being, combine benefic and malevolent aspects, thus man carries within himself this vital polarity of Good and Evil.

Apart from the Mother-Goddess, the principal divine personifications are her four sons and, next to them, a large number of spirit-owners, the masters of the different aspects of Nature, the rulers over rituals, and the beings that govern certain actions. That all these supernatural beings are the appointed guardians of certain aspects of human conduct—cultural or biological—has many ethical implications that provide the basis for the concept of sin. When the divine beings established the world order, however, they made provision for individual interpretation and thus confirmed a person's autonomy of moral choice. Life is a mixture of good and evil and, as the Kogi point out very frequently, there can be no morality without immorality. According to Kogi ethics one's life should be dedicated entirely to the acquisition of knowledge, a term by which are meant the myths and traditions, the songs and spells, and all the rules that regulate ritual. This body of esoteric knowledge is called by the Kogi the "Law of the Mother." Every object, action, or intention has a spirit-owner who jealously guards what is his own, his privilege, but who is willing to share it with mankind if compensated by an adequate offering. The concept of offerings, then, is closely connected with divinatory practices because it is necessary to determine the exact nature of the offerings that will most please a certain spirit-being. These details—some of them esoteric trivia but nonetheless functional units of a complex whole—can only be learned in the course of many years. Closely related to this body of knowledge, Kogi learning includes a wide range of information on phenomena that might be classified as belonging to tribal history, geography, and ecology, animal and plant categorization, and a fair knowledge of anatomy and physiology.

But all this knowledge has a single purpose: to find a balance between Good [persistence] and Evil [dissolution] and reach old age in a state of wisdom and tolerance [sapience]. The process of establishing this balance is called yulúka, an expression that might be translated as "to be in agreement with" or "to be in harmony with." One should be careful, however, not to see in this concept a kind of romantic Naturphilosophie, of noble savages living in harmony with nature, but take it for what it is—a harsh sense of reality paired, at times, with a rather cynical outlook on human affairs. The concept of yulúka does not stand for blissful tranquility, but means grudging acceptance of misfortune, be it sickness or hunger, the treachery of one's closest of kin, or the undeserved ill will of one's neighbor. A Kogi, when faced with hardships or high emotional tensions will rarely dramatize his situation, but will rather try to establish an "agreement" by a process of rationalization.

Another philosophical concept of importance is called aluna. There are many possible translations ranging from "spiritual" to "libidinous," and from "powerful" to "traditional" or "imaginary." Sometimes the word is used to designate the human soul. An approximate general translation would be "otherworldly," a term that would imply supernatural power with vision and strength, but otherwise the meaning of this concept has to be illustrated by examples, to convey its significance to the outsider. For example, to say that the world was created "in aluna" means that it was designed by a spiritual effort. The deities and the tribal ancestors exist in aluna, that is, in the Otherworld, and in an incorporeal state. Similarly, it is possible to deposit an offering in aluna at a certain spot, without really visiting that place. A man might sin in aluna, by harboring evil intentions. And to go further still: to the Kogi, concrete reality quite often is only appearance, a semblance that has only symbolic value, while the true essence of things exists only in aluna. According to the Kogi, one must therefore develop the spiritual faculty to see behind these appearances and to recognize the aluna of the Universe.

The divine personifications of the Kogi pantheon are not only continuously demanding offerings from men but, being guardians of the moral order, also watch any interaction between morals, and punish the breaking of the rules that govern interpersonal relations. The Kogi put great emphasis on collaboration, the sharing of food, and the observance of respectful behavior toward elders and other persons of authority. Unfilial conduct, the refusal to work for one's father-in-law, or aggressive behavior of any kind are not only social sins, but are transgressions of the divine rules, and for this the offender is bound to incur the displeasure of the divine beings. Among the worst offenses are violations of certain sexual restrictions. Kogi attitudes toward sex are dominated by deep anxieties concerned with the constant fear of pollution, and prolonged sexual abstinence is demanded of all men who are engaged in any ritual activity. The great sin is incest, and the observation of the rules of exogamy is a frequent topic of conversations and admonitions in the ceremonial house.

Kogi culture contains many elements of sexual repression, and there is a marked antifeminist tendency. The men consider the acquisition of esoteric knowledge to be the only valid objective in life and claim that women are the prime obstacle on the way of achieving this goal [for aluna challenged men]. Although a Kogi husband is expected to be a dutiful provider and should produce sufficient food to keep his family in good health, it is also stated that a man should never work for material gain and should not make efforts to acquire more property than he needs in order to feed and house his family [a culture of enough, not MORE!]. All his energies should be spent on learning, on taking part in ritual, and on acquiring the necessary knowledge of procedure and moral precepts to contribute to the maintenance of the ordained world order [which the women, by nature more attuned to aluna, do not need to be drugged or undergo repression]. Now women have very few ritual functions and, except when quite old, show but little interest in metaphysical matters. To them the balance of the Universe is of small concern; they eat, they sleep, they chat and idle; in other words, to a Kogi man they personify all the elements of indulgence, of disruption, and of irresponsibility. "They are like cockroaches," the Kogi [men] grumble, "always near the cooking place, and eating all the time!" Besides, Kogi women are not squeamish about sex and, being oblivious to the delicate details of ritual purity, appear to their men as eternal temptresses bent upon destroying the social order and, with it, the religious concepts that are so closely connected with it.

The Kogi are a deeply religious people and they are guided in their faith by a highly formalized priesthood [intelligentsia?]. Although all villages have a headman who nominally represents civil authority, the true power of decision in personal and community matters is concentrated in the hands of the native priests, called mámas. These men, most of whom have a profound knowledge of tribal custom, are not simple curers or shamanistic practitioners, but fulfill priestly functions, taught during years of training and exercised in solemn rituals. The mámas are sun-priests who, high up in the mountains behind the villages, officiate in ceremonial centers where people gather at certain times of the year, and each ceremonial house in a village is under the charge of one or two priests who direct and supervise the nightlong meetings of men when they gather in the settlement. The influence of this priesthood extends to every aspect of family and village life and completely overshadows the few attributes of the headmen.

To begin with, all people must periodically visit a priest for confession—in private or in public—of all their actions and intentions. An important mechanism of control [of men] is introduced here by the idea that sickness is, in the last analysis, the consequence of a state of sinfulness incurred by not living according to the "Law of the Mother." A man will therefore scrutinize his conscience in every detail and will try to be absolutely honest about his actions and intentions, to avoid falling ill or to cure an existing sickness. Confession takes place at night in the ceremonial house [hence women don't 'confess'], the mámas reclining in his hammock while the confessant sits next to him on a low bench. The other men must observe silence or, at least, converse in subdued voices, while between the priest and the confessant unfolds a slow, halting dialogue in which the máma formulates several searching questions about the confessant's family life, social relations, food intake, ritual obligations, dreams, and many other aspects of his daily life. People are supposed to confess not only the actual fault they have committed, but also their evil intentions, their sexual or aggressive fantasies, anything that might come to their minds under the questioning of the priest. The nagging fear of sickness, the hypochondriacal observation and discussion of the most insignificant symptoms, will make people completely unburden themselves. There can be no doubt that confession is a psycho-therapeutic institution of the first order, within the general system of Kogi religion [social control system primarily of men; women have female priests, but fewer are needed].

To act as a confessor to people as metaphysically preoccupied as the Kogi puts high demands upon a máma's intelligence and empathy; his role is never that of a passive listener but he must be an accomplished conversationalist, able to direct the confessant's discourse into channels that allow him to probe deeply into the troubled mind of his confidant. But confession in the ceremonial house is not the only occasion when an individual can relieve himself of his intimate doubts and conflicts. At any time, any man, woman, or child can approach a máma and ask him for advice. It is natural then that a máma obtains, in this manner, much information on individual attitudes and community affairs which allows him to exercise control over many aspects of local sociopolitical development. I know of no case, however, where a máma would have taken advantage of this knowledge for his own ends. The mámas constitute a truly moralizing force and, as such, occupy a highly respected position [pursuit of short-term self-interests is not the norm, unlike in modern techno-industrial society].

Kogi priests are the products of a long and arduous training, under the strict guidance of one or several old and experienced mámas. In former times it was the custom that, as soon as a male child was born, the máma would consult in a trance the Mother-Goddess, to ascertain whether or not the newborn babe was to be a future priest. It is also said that a máma might dream the name of a certain family and thus would know that their newborn male child would become a priest. Immediately the máma would then "give notice" to the newborn during a visit to his family, and it is pointed out that, in those times, the parents would have felt greatly honored by the knowledge that their son would eventually become a priest. From several traditions it would appear that certain families or, rather, patrilines, may have had hereditary preeminence in priesthood, and even today priests belonging to a high-ranking exogamic group are likely to be more respected than others.

Ideally, a future priest should receive a special education since birth; the child would immediately be separated from his mother and given into the care of the máma's wife, or any other woman of childbearing age whom the máma might order to join his household as a wet nurse. But occasionally the mother herself would be allowed to keep the child, with the condition that he be weaned before reaching the age of three months. From then on the child would have to be fed a mash of ripe bananas and cooking plantains, and soon afterwards would have to be turned over to the máma's family. If, for some reason, a family refused to give up the child, the civil authorities might have to interfere and take the child away by force. It was always the custom that the family should pay the máma for the education of the boy, by sending periodically some food to his house, or by working in his fields.

These ideal conditions, it might be said, probably never existed; under normal circumstances—and this refers also to the present situation—the training begins at about two or three years of age, but certainly not later than the fifth year, and then continues through childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood, until the novice, aged now perhaps twenty or twenty-two, has acquired his new status as máma by fulfilling all necessary requirements. The full training period should be eighteen years, divided into two cycles of nine years each, the novice reaching puberty by the end of the first cycle.

There exist about three or four places in the Sierra Nevada where young people are being trained for the priesthood. In each place, two, or at most, three boys of slightly different ages live in an isolated valley, far from the next village, where they are taken into the care of their master's family. The geographical setting may vary but, in most cases, the small settlement, consisting of a ceremonial house and two or three huts, is located at a spot that figures prominently in myth and tradition. It may be the place where a certain lineage had its origin, or where a culture hero accomplished a difficult task; or perhaps it is the spot where one of the many spirit-owners of Nature has his abode. In any case, the close association of a "school" with a place having certain religious-historical traditions is of importance because at such a spot there exists the likelihood of ready communication with the supernatural sphere; it is a "door," a threshold, a point of convergence, besides being a place that is sacred and lies under the protection of benevolent spirit-beings.

The institution of priestly training has a long and sacred tradition among the Kogi. Several lengthy myths tell of how the four sons of the Mother-Goddess created Mount Doanankuivi, at the headwaters of the Tucurince River and, inside the mountain, built the first ceremonial house where novices were to be trained for the priesthood. The first legendary máma to teach such a group of disciples was Búnkuasé, "the shining one," is the personification of the highest moral principles in Kogi ethics and is thus taken to be the patron and spiritual guardian of the priesthood. It is, however, characteristic of Kogi culture that there should exist several other traditions according to which it is Kashindúkua, also a son of the Mother-Goddess, had been destined by her to be a great curer of human ills, a thaumaturge able to extract sickness from the patient's body as if it were a concrete, tangible substance. But occasionally, and much to his brother's grief, he misused his powers and then did great harm to people. Kashindúkua came to personify sexual license and, above all, incest but, as an ancient priest-king, curer, and protector of all ceremonial houses, he continues to occupy a very important place in the Kogi pantheon.

A novice, training for the priesthood, is designated by the term kuívi (abstinent). This concept refers not only to temperance in food and drink, but also to sex, sleep, and any form of overindulgence. This attitude of ascetic self-denial is said to have been the prime virtue of the ancient mámas of mythical times. But, as always, the Kogi introduce an element of ambivalence, of man's difficult choice of action, and also tell of outstanding sages and miracle workers who, at the same time, were great sinners.

At the level of cultural development attained by the Kogi, the teacher position is well recognized and there is full agreement that all priests must undergo a long process of organized directed training, in the course of which the novice's education is functionally specialized. The ideal image of the great teacher and master, the ancient sage, is often elaborated in myths and tales, and in their context the máma is generally represented as a just but authoritarian father figure. In the great quest for knowledge and divine illumination, the teacher never demands from his pupils more than he himself is willing to give; he suffers patiently with them and is a model of self-control and wisdom. In other tales, the opposite is shown, the vicious hypocrite who stuffs himself with food while his disciples are fasting, or the lecherous old man who seduces nubile girls while publicly preaching chastity. These images of the saint and the sinner—patterned after those of the hero and the villain, in another type of tale—are always present in Kogi thought and, in many aspects, are statements of the importance society attributes to the role of the priesthood. Some of these tales are really quite simplistic in that they tend to measure a máma's stature merely in terms of his cunning, his reconciliatory abilities, rote memory, or miracle-working capacity, but other tales contain examples of true psychological insight, high moral principles, and readiness for self-sacrifice. The image of the teacher is thus well defined—though somewhat stereotyped—in Kogi culture and is also referred to in situations that lie quite outside the sphere of priestly training and that are connected—to give some examples—to the acquisition of skills, the tracing of genealogical ties, or the interpretation of natural phenomena [observational systems ecology]. On the one hand, then, it is plain that not all mámas are thought to be adequate teachers and to be trusted with the education of a small child. On the other hand, not all mámas will accept disciples; some live in abject poverty, others are in ill health, and others still feel disinclined to carry the responsibilities that teaching entails. Old age is not of the essence if it is not accompanied by an alert mind and a manifestly "pure" behavior, and quite often a fairly young máma has great renown because of his high moral status, while older men are held in less esteem.

The novices should spend most of their waking hours inside the ceremonial house. In former times they used to live in a small enclosure (hubi) within the ceremonial structure, but at present they sleep in one of the neighboring huts. This hut, which is similar to the ceremonial house but smaller, has an elaborate roof apex and the walls of plaited canes have two doors at opposite points of the circumference, while the hut of the máma's family lacks the apex and has only one door. All during their long training the novices must lead an entirely nocturnal life and are strictly forbidden to leave the house in daylight. Sleeping during the day on low cots of canes placed against the walls, the novices rise after sunset and, as soon as darkness has set in, are allowed to take their first meal in the kitchen annex or outside the máma's house. A second meal is taken during the night, the novices are not supposed to go outside except in the company of a máma and then only for a short walk. The principal interdictions, repeated most emphatically over and over again, refer to the sun and to women; a novice should be educated, after weaning, only by men and among men, and should never see a girl or a woman who is sexually active; and throughout his training period, he should never see the sun nor be exposed to his rays, "The sun is a máma," the Kogi say; "And this máma might cause harm to the child." When there is a moon, a novice should cover his head with a specially woven basketry tray (güíshi) when leaving the house at night.

During their training period the novices are supervised and strictly controlled by one or two attendant wardens (hánkúkua-kúkui), adult men who have joined the máma's household, generally after having spent some years as novices under his guidance. These wardens are mainly in charge of discipline, but may occasionally participate to some degree in the educational process, according to the máma's orders.

Apart from the little group of people who constitute the settlement—the máma and his family, the wardens, and some aged relatives of either—the novices should avoid any contact with other people; in fact, they should never even be seen by an outsider. The manifest danger of pollution consists in the presence of people who are in contact with women; should such a person see a novice or should he speak to him, the latter would immediately lose the spiritual power he has accumulated in the course of his apprenticeship. It is supposed, then that the community consists only of "pure" people, that is, of persons who abstain from any sexual activity and who also observe very strict dietary rules.

As in many primitive educational systems, the observance of dietary restrictions is a very important point in priestly training. In general, a novice should soon learn to eat sparingly and, after puberty has been reached, should be able to go occasionally without food for several days. He should soon learn to eat little meat, but rather fowl such as curassow, and should avoid all foodstuffs that are of non-Indian origin such as bananas, sugar cane, onions, or citrus fruits. He should never, under any circumstances, consume salt, nor should he use any condiments such as peppers. A novice, it may be added here, should not touch his food with his left hand because this is the "female" hand and is polluted. During the first nine years the prescribed diet consists mainly of some small river catfish and freshwater shrimp, certain yellow-green grasshoppers of nocturnal habits, land snails collected in the highlands, large black túbi beetles, and certain white mushrooms. Vitamin D appears to be sufficient to compensate for the lack of sunlight during these years. Three or four different classes of maize can also be eaten, as well as some sweet manioc, pumpkins, and certain beans. Some mámas insist that all food consumed by the novices should be predominantly of a white color: white beans, white potatoes, white manioc, white shrimps, white land snails, and so forth. Only after puberty are they allowed to eat, however sparingly, the meat of game animals such as peccary, agouti, and armadillo. These animals, it is said, "have great knowledge, and by eating their flesh the novices will partake in their wisdom." In preparing their daily food, only a clay pot made by the máma himself should be used and all food should be boiled, but never fried nor smoked. Shoe-shaped vessels (or, rather, breast-shaped ones) are used especially for the preparation of a ritual diet based on beans.

The boys are dressed in a white cotton cloth woven by the máma or, later on, by themselves, which is wrapped around the body, covering it from under the armpits to the ankles, and held in place by a wide woven belt. For adornment they wear bracelets, armlets, necklaces, and ear ornaments, all of ancient Tairona origin and made of gold, gilded copper, and semiprecious stones. There is emphasis on cleanliness and at night the boys go to bathe in the nearby mountain stream.

In former times, that is, perhaps until three or four generations ago, it was the custom to educate also some female children who, eventually, were to become the wives of the priests. The girls were chosen by divination and then were brought up by the wife of a máma. Aided by other old women, the girls were taught many ancient traditions primarily referring to the dangers of pollution. They were trained to prepare certain "pure" foods, to collect aromatic and medical herbs, and to assist in the preparation of minor rituals. At present, the education of girls under the guidance of a máma's wife is institutionalized in some parts, but the aim is not so much to prepare spouses for future priests than to educate certain intelligent girls "in the manner of the ancients" and send them back to their families after a few years of schooling, so they can teach the womenfolk of their respective villages the traditions and precepts they have learned in the máma's household, and be thus living examples of moral conduct.

But I must return now to the boy who has been taken into a strange family and who is now undergoing a crucial period of adaptation.

The novice is exposed to the varied influences of a setting that differs notably from that of his own family. Although the child will find in the máma's household a certain well-accustomed set of familial behavioral patterns, he is made aware that he now lives in a context of nonkin. This is of special relevance where the novice was educated for the first three or four years by his own family and has thus acquired a certain cultural perspective that, in his new environment, is likely to differ from the demands made by the máma's kin. Between teacher and pupil, however, there generally develops a fairly close emotional tie; the novice addresses the máma with the term hátei (father), and he, in turn, refers to his disciples as his "children," or "sons." Only after the novice has reached puberty does the apprentice-master relationship usually acquire a more formal tone.

During the first two years of life, Kogi children are prodded and continuously encouraged to accelerate their sensory-motor development: creeping, walking, speaking. But in later years they are physically and vocally rather quiet. A Kogi mother does not encourage response and activity, but rather tries to soothe her child and to keep him silent and unobtrusive. Very strict sphincter training is instituted, and by the age of ten or twelve months the boy is expected to exercise complete control during the daytime hours. Play activity is discouraged by all adults and, indeed, to be accursed of "playing" is a very serious reproach. There are practically no children's games in Kogi culture and for this reason a teacher's complaints refer rather to lack of attention or to overindulgence in eating or sleeping, than to any boisterous, playful, or aggressive attitudes.

Although older children are sometimes scolded for intellectual failures, the Kogi punish or reward children rather for behavioral matters. Punishment is often physical; a máma punishes an inattentive novice by depriving him of food or sleep, and quite often beats him sharply over the head with the thin hardwood rod he uses to extract lime from his gourd-container when he is chewing coca. For more serious misbehavior, children may be ordered to kneel on a handful of cotton seeds or on some small pieces of a broken pottery vessel. A very painful punishment consists in kneeling motionless with horizontally outstretched arms while carrying a heavy stone in each hand.

In practically all ceremonial houses one can see a large vertical loom leaning against the wall, with a half-finished piece of cloth upon it. The weaving of the coarse cotton cloth the Kogi use for the garments of both sexes is a male activity and has a certain ritual connotation. But to weave can also become a punishment. An inattentive novice—or a grown-up who has disregarded the moral order—can be made to weave for hours, sitting naked in the chill night and frantically working the loom, while behind him stands the máma who prods him with his lime rod, sometimes beating him over the ears and saying: "I shall yet make you respect the cloth you are wearing!"

Life in the ceremonial house is characterized by the regularized scheduling of all activities and thus expresses quite clearly a distinct learning theory. We must, first of all, look at the general outline of the aims of education. In doing so, it is necessary to use categories of formal knowledge in the way they are defined in our culture, a division that would make no sense to a Kogi, but which is useful here to give an order to the entire field of priestly instruction. The main fields of a máma's learning and competence are, thus, the following:

- Cosmogony, cosmology, mythology

- Mythical social origins, social structure, and organization

- Natural history: geology, meteorology, botany, zoology, astronomy, biology

- Linguistics: ceremonial language, rhetoric

- Sensory deprivations: abstinence from food, sleep, and sex

- Ritual: dancing and singing

- Curing of diseases

- Interpretation of signs and symbols, dreams, animal behavior

- Sensitivity to auditory, visual, and other hallucinations

The methods by which these aims of priestly education are pursued are many and depend to a high degree upon the recognition of a sequence of stages in the child's mental and physical development. During the early years of training, at about five or six years of age, the child is literally hand-reared, in that he is in very frequent physical contact with or, at least, proximity to, his teacher. While sitting on a low bench, the máma places both hands upon the hips of the boy who stands before him and rhythmically pushes and bends the child's body to the tune of his songs or recitals, or while marking the pace with a gourd-rattle. During this period, the Kogi say, the child "first learns to dance and only later learns to walk."

During the first two years of training, the teaching of dances is accompanied only by the humming of songs and by the sound of the rattle; only later on are the children taught to sing. During these practices the children always wear heavy wooden masks topped with feather crowns and are adorned with all the heavy ornaments mentioned above. The peculiar restriction of body movements caused by the stiff ceremonial attire and the hands of the teacher produce a lasting impact on the child, and even decades later, people who have passed through this experience refer to it with a mixture of horror and pride. For hours on end, night after night, and illuminated only by torches and low-burning fires, the children are thus taught the dance steps, the cosmological recitals, and the tales relating to the principal personifications and events of the Creation story. Many of the songs and recitations are phrased in the ancient ceremonial language which is comprehensible only to an experienced máma, but which has to be learned by the novices by sheer memorization. During these early years, myths, songs, and dances become closely linked into a rigid structure that alone—at least, at that time—guarantees the correct form of presentation.

One of the main institutionalized teaching concepts consists in iterative behavior. This is emphasized especially during the first half of the curriculum, when the novices are made to repeat the myths, songs, or spells until they have memorized not only the text and the precise intonation, but also the body movements and minor gestures that accompany the performance. Rhythmic elements are important and the learning of songs and recitals is always combined with dancing or, at least, with swaying motions of the body. This is not a mere mechanistic approach to the learning process and does not represent a neurally based stimulus-response pattern, but the child is simultaneously provided with a large number of interpretative details that make him grasp the context and meaning of the texts.

Between the end of the first nine-year cycle of education and the onset of the second cycle, the novice reaches puberty. It is well recognized by the Kogi that during this period significant personality changes occur, and for this reason allowance is made for the eventual interruption of the training process or, as a matter of fact, for its termination. Having reached puberty, a boy who fails to display a truly promising attitude toward priesthood, demonstrated, above all, by his repressive attitude toward sexuality, is allowed to return to his family. At no time is such a boy forced to stay on, even if he should wish to do so; if his master believes that the youth does not have the calling to become a máma, he will insist on his returning to his people. But these cases seem to be the exception rather than the rule; more often puberty is reached as a normal transition, and a few years later, at the age of fourteen or fifteen years, the boy is initiated by the máma and receives from him the lime container and the little rod—a female and a male symbol—together with the permission to chew from now on the coca leaves the youth forthwith toasts in a special vessel.

Ideally, a Kogi priest should divest himself of all sensuality and should practice sexual abstinence, but this prohibition is contradicted in part by the rule that all nubile girls must be deflowered by the máma who, alone, has the power to neutralize the grave perils of pollution that according to the Kogi are inherent in this act. Similar considerations demand that, at puberty, a boy should be sexually initiated by the máma's wife or, in some cases, by an old woman specially designated by the máma. During the puberty ritual of a novice, the master's wife thus initiates the youth, an experience fraught with great anxiety and which is often referred to in later years as a highly traumatic event.

During the second cycle, the teachings of the master concentrate upon divinatory practices, the preparation of offerings, the acquisition of power objects, and the rituals of the life cycle. During this period, education tends to become extremely formal because now it is much more closely associated with ritual and ceremony. The youth is taught many divinatory techniques, beginning with simple yes-or-no alternatives, and going on to deep meditation accompanied by exercises of muscular relaxation, controlled breathing, and the "listening" to sudden signs or voices from within. Power objects are acquired slowly over the years and consist of all kinds of "permits" (sewá) granted by the spirit-owners of Nature. Most of these permits consist of small archaeological necklace beads of stone, of different minerals, shapes, colors, and textures, that are given to the novice as soon as he has mastered the corresponding knowledge. At that age, a novice will need, for example, a permit to chew coca, to eat certain kinds of meat, to perform certain rituals, or to sing certain songs. During this period the novices are also taught the complex details of organization of the great yearly ceremonies that take place in the ceremonial centers, higher up in the mountains.

The novices have ample opportunity to watch their master perform ritual actions, a process during which a considerable body of knowledge is transmitted to them. The seasons of the year are paced with special ritual markings: equinoxes and solstices, planting and harvesting, the stages of the individual life cycle. Now that they themselves begin to perform minor rituals, the recurrent statements contained in the texts, together with the identical behavioral sequences, become linked into a body of highly patterned experiential units. The repetition of the formulas, "This is what happened! Thus spoke our forefathers! This is what the ancient said!" insists upon the rightness, the correctness of the actions and contents that constitute ritual.

During the education of a novice there is no skill training to speak of. Kogi material culture, it has been said already, is limited to an inventory of a few largely undifferentiated, coarse utilitarian objects, and the basic skills of weaving or pottery making—both male activities—are soon mastered by any child. There is hardly any specialization in the manufacture of implements and a máma is not expected to have any manual or artistic abilities. He is not a master-craftsman; as a matter of fact, he should avoid working with his hands because of the ever-present danger of pollution.

Language training, however, is a very different matter. In the first place, since early childhood the novice learns a very large denotative vocabulary. The Kogi are fully aware that any intellectual activity depends upon linguistic competence and that only a very detailed knowledge of the language will permit the precise naming of things, ideas, and events, as a fundamental step in establishing categories and values. In part, linguistic tutoring is concerned with correctness of speech, and children are discouraged from using expressions that are too readily associated with their particular age group. As most of the linguistic input comes from a máma, the novices soon demonstrate a very characteristic verbal behavior consisting of well-pronounced, rather short, sentences, with a rich vocabulary, and delivered in an even but very emphatic voice.

While in normal child-training techniques care is taken to transmit a set of simple behavioral rules that tend to advance the child's socialization process, in training for the priesthood socialization is not a desirable goal. An average child is taught to collaborate with certain categories of people and is expected to lend a helping hand, to share food, to be of service to others. Emphasis is placed on participation in communal labor projects such as road building, the construction of houses or bridges, or on attendance at meetings in which matters of community interest are being discussed. But priestly education does not concern itself with these social functions of the individual. On the contrary, it is evident that a máma is quite intentionally trained not to become a group member, but to stand apart, aloof and superior. To the Kogi, the image of the spiritual leader is that of a man whose ascetic hauteur makes him almost unapproachable. A máma should not be too readily accessible, but should keep away from the discussion of public affairs and the petty details of local power politics, because only by complete detachment [view through macroscope] and by the conscious elimination of all emotional considerations [like/dislike, for/against] can he become a true leader of his people.

This aloofness, this standing alone, is, in part, the consequence of the narrow physical and social environment in which the novices spend their long formative years of schooling. They are socialized, of course, but they are socialized in a context of a very small and very select group of people associated into a unit that is not at all representative of the larger society. It is a fact that the novice learns very little about the practical aspects of the society of which he is eventually becoming a priest. Life in the ceremonial house or in the small group of the máma's family does not give the novices enough social contacts to enable them to obtain a clear picture of the wider society. It is a fact that, during the years of a priest's training period, he hardly becomes acquainted with the practical aspects of land tenure and land use, of seed selection and soil qualities, or of the ways in which gossip, prestige, envy, and the wiles of women are likely to affect society. A novice brought up quite apart from society forms an image of the wider scene, which, at best, is highly idealized, and at worst, is an exaggeration of its evils and dangers.

In Kogi culture, sickness and death are thought to be the direct consequences of sin, and sin is interpreted mainly in terms of sex. Even in those relationships that are culturally approved, that is, in marriage between partners belonging to complementary exogamic units, the Kogi always see an element of pollution, of contamination, because most men are periodically engaged in some ritual demanding purity, abstinence, fasting, attendance at nightly sessions in the ceremonial house, or prolonged travel to some sacred site. Kogi women are often, therefore, quite critical of male religious activities, being in turn accused by their husbands of exercising a "weakening" influence upon their minds, which are bent upon the delicate task of preserving the balance of the Universe. Kogi priests live in a world of myth, of heroic deeds and miraculous events of times past, in which the female characters appear cast in the role of evil temptresses. To a young priest who, after years of seclusion, finally returns to village life and community affairs, women constitute the main danger to cultural survival and are a direct threat to the moral order. Therefore, it again takes several years before the máma learns about life in society and acquires a practical understanding of the daily problems of life.

Moral education is, of course, at the core of a priest's training. Since childhood, a common method of transmitting a set of simple moral values consists in the telling and retelling of the "counsels," cautionary tales of varying length that contain a condensed social message. These tales are interpersonal relations within the family setting: husband and wife, elder brother and younger brother, son-in-law and father-in-law, and so on. Other tales might refer to some famous máma of the past, to culture heroes and their exploits, or to animals that behave like humans. The stories are recited during the nightly sessions when a group of men has gathered or they are told to an individual who has come for advice. In all these stories, what is condemned is overindulgence in food, sleep, and sex; physical aggressiveness is proscribed; theft, disrespectful behavior, and cruelty to children and animals are disapproved of, and inquisitiveness by word or deed is severely censured, especially in women and children. Those qualities that receive praise are economic collaboration, the sharing of food, the willingness to lend household utensils, respectful attitudes towards one's elders, and active participation in ritual. The behavioral message is quite clear and there are no ambivalent solutions: the culprits are punished and the virtuous are rewarded. These counsels, then, do not explain the workings of the Universe and are not overburdened with esoteric trivia, but refer to matters of daily concern, to commonplace events and to average situations. They form a body of entertaining, moralizing stories that can be embroidered or condensed to fit the situation. It may be mentioned here that it is characteristic of the highly impersonal quality of social relations among the Kogi that friendship is not a desirable institution. It is too close, too emotional a relationship, and social rules quite definitely are against it.

It is evident that the counsels constitute a very simplistic level of moral teaching. These stories are useful in propagating some elementary rules among the common people; they are easy to remember and their anecdotal qualities and stereotyped characters have become household words. Everyone knows the story of Sekuishbúchi's wife or how Máma Shehá forfeited his beautiful dress. But it is also obvious that there is another, deeper level where the moral issues are far more complex.

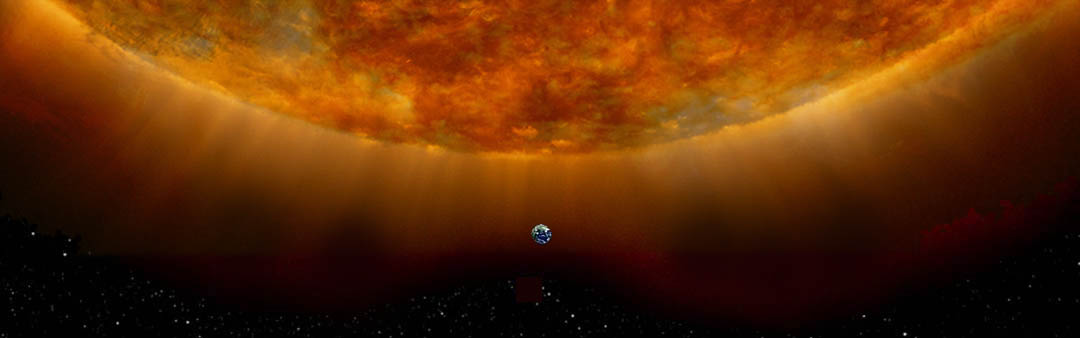

According to the Kogi, our world exists and survives because it is animated by solar-energy [ecological energetics 101, aka reality 101]. This energy manifests itself by the yearly round of seasons that coincides with the position of the sun on the horizon at the time of the solstices and equinoxes. It is the máma's task to "turn back the sun" when he advances too far and threatens to "burn the world," or to "drown it with rain," and only by thus controlling the sun's movements with offerings, prayers, and dances can the principles of fertility be conserved. This control of the mámas, however, depends on the power and range of their esoteric knowledge and this knowledge, in turn, depends upon the purity of their minds. Only the pure, the morally untainted, can acquire the divine wisdom to control the course of the sun and, with it, the change of the seasons and the times for planting and harvesting. It is for this reason that the Kogi, both priests and laymen, are deeply concerned about the education of future generations of novices and about their requirements of purity. Their survival as well as that of all mankind depends on the moral stature of Kogi priests, now and in the future; and it is only natural, then, that the correct training of novices should be of profound concern to all.

The Kogi claim to be the "elder brothers" of mankind and, as they believe they are the possessors of the only true religion, they feel responsible for the moral conduct of all men. There is great interest in foreign cultures, in the strange ways of other peoples, and the Kogi readily ask their divine beings to grant protection to the wayward "younger brothers" of other nations. The training of more novices is, therefore, a necessity not only for Kogi society, but also for the maintenance of the wider moral order.

From the preceding pages it would, perhaps, appear that, during all these years of priestly education, most knowledge is acquired by rote memory or by the endless repetition of certain actions meant to transmit a set of socioemotional messages that are not always fully understood by the novice, but have to be dealt with nevertheless. But it would be a mistake to think that training for the priesthood consists only, or mainly, of these repetitious, empty elements of a formalized ritual. The true goals of education [insight, love, understanding] are quite different and the iterative behavior described above is only a very small part of the working behavior of the novices.

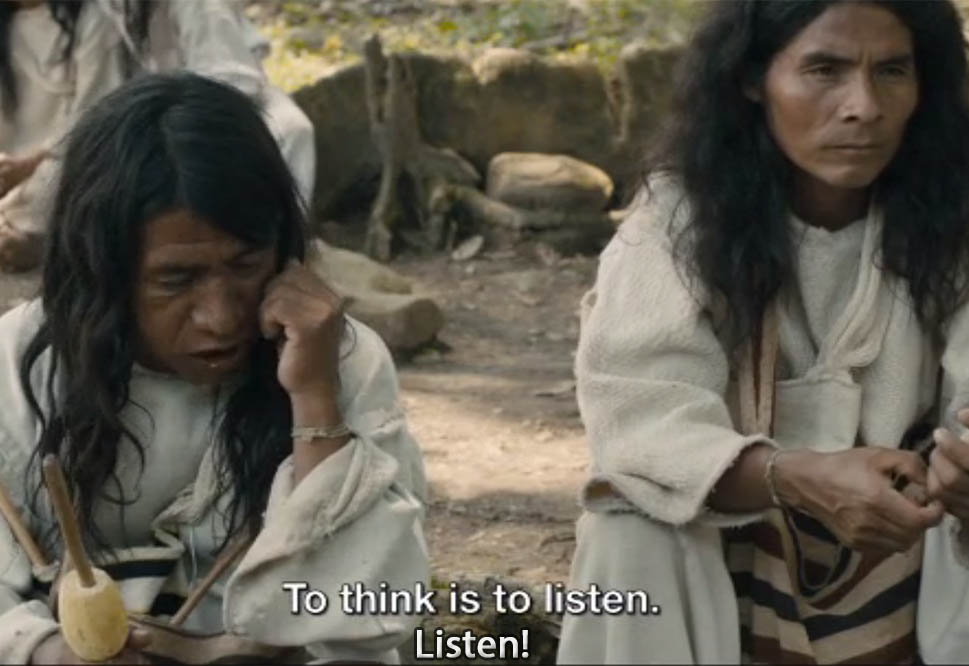

First of all, the aim of priestly education is to discover and awaken those hidden faculties of the mind that, at a given moment, enable the novice to establish contact with the divine sphere. The mámas know that a controlled set or sequence of sensory privations eventually produces altered states of consciousness enabling the novice to perceive a wide range of visual, auditory, or haptic hallucinations. The novice sees images and hears voices that explain and extol the essence of being, the true sources of Nature, together with the manner of solving a great variety of common human conflict situations. In this way, he is able to receive instructions about offerings to be made, about collective ceremonies to be organized, of sickness to be cured. He acquires the faculty of seeing behind the exterior appearances of things and perceiving their true nature. The concept of aluna, translated here as "inner reality," tells him that the mountains are houses, that animals are people, that roofs are snakes, and he learns that this manipulation of symbols and sign is not a simple matter of one-to-one translation, but that there exist different levels of interpretation and complex chains of associations. The Kogi say: "There are two ways of looking at things; you may, when seeing a snake, say: 'This is a snake,' but you may also say: 'This is a rope I am seeing, or a root, an arrow, a winding trail,'" Now, from the knowledge of these chains of associations that represent, in essence, equivalences, he acquires a sense of balance, and when he has achieved this balance he is ready to become a priest. He then will practice the concept of yulúka, of being in agreement, in harmony, with the unavoidable, with himself, and with his environment [be 'right with reality'], and he will teach this knowledge to others, to those who are still torn by the doubts of polarity [dualism].

The entire teaching process is aimed at this slow, gradual building up to the sublime moment of the self-disclosure of god to man, of the moment when Sintána or Búnkuasé or one of their avatars reveals himself in a flash of light and says: "Do this! Go there!" Education, at this stage, is a technique of progressive illumination. The divine personification appears bathed in a heavenly light and, from then on teaches the novice at night. From out of the dark recesses of the house comes a voice and the novice listens to it and follows its instructions. A máma said: "These novices hear everything and know everything but they don't know who is teaching them."

To induce these visionary states the Kogi use certain hallucinogenic drugs the exact nature of which is still uncertain. Two kinds of mushrooms, one of them a bluish puffball, are consumed only by the mámas, and a strong psychotropic effect is attributed to several plants, among them to the chestnutlike fruits of a large tree (Meteniusa edulis). But hallucinatory states can, of course, be produced endogenously by sensory privations and other practices; most trancelike states during which the mámas officiate at certain rituals are produced, in all probability, by a combination of ingested drugs and strenuous body exercise. The Kogi say: "Because the mámas were educated in darkness, they have the gift of visions and of knowing all things, no matter how far away they might be. They even visit the Land of the Dead."

In the second place, an important aspect of priestly education consists of training the novice to work alone. Although a Kogi priest has many social functions, his true self can find expression only in the solitary meditation he practices in his hut when he is alone. In order to evaluate people or events, he must be alone; he may discuss occasionally some difficult matter with others, but to arrive at a decision, he must be quite alone. This ability to stand alone and still act on behalf of others is a highly valued behavioral category among the Kogi, and children, although they often learn by participation, are trained already at an early age to master their fears and doubts and to act alone. A máma's novice might be sent alone, at night, to accomplish a dangerous task, perhaps a visit to a spot where an evil spirit is said to dwell, or a place that is taken to be polluted by disease. A máma takes pride in climbing—alone—a steep rock, or in crossing a dangerous cleft, and he readily faces any situation that, in the eyes of others, might entail the danger of supernatural apparitions of a malevolent type.

But what really counts is his moral and intellectual integrity, his resolution when faced with a choice of alternative actions. The adequate evaluation of his followers' attitudes and needs requires a sense of tolerance and a depth of understanding of human nature, which can only be attained by a mind that is conscious of having received divine guidance.

The final test comes when the master asks the novice to escape from the tightly closed and watched ceremonial house. The novice, in his trance, roams freely, visiting faraway valleys, penetrating into mountains, or diving into lakes. And when telling them of the wanderings of his soul, the others will say: "You have learned to see through the mountains and through the hearts of men. Truly, you are a máma now!"

The education of a máma is, essentially, a model for the education of all men. Of course, not everyone can or should become a máma, but all men should follow a máma's example of frugality, moderation, and simple goodness. There are no evil mámas, no witch doctors or practitioners of aggressive magic; they only exist in myths and tales of imagination, as threatening examples of what could be. On the contrary, Kogi priests are men of high moral stature and acute intellectual ability, measured by any standards, who are deeply concerned about the ills that afflict mankind and who, in their way, do their utmost to alleviate the burdens all men have to carry. But they are also quite realistic in their outlook. An old máma once said to me: "You are asking me what is life; life is food, a woman—then, a house, a field—then, god."

Reflecting back on what was said at the beginning of this essay where I tried to trace an outline of Kogi culture, it is clear that priestly education constitutes a very coherent system that, as a model of conduct, obeys certain powerful adaptive needs [survival/sustainability needs].

Kogi culture is characterized by a marked lack of specificity in object relations. To a Kogi, people can exist only as categories, such as women, children, in-laws, but not as individuals among whom close emotional bonds might be established. The early weaning of the child is only the beginning of a series of mechanisms by which all affective attachments are severed. Sphincter training, accomplished at about ten months, reinforces this independence of affective rewards. A child's crying is never interpreted as an expression of loneliness and the need for affection, and a baby is always cared for by several mother-substitutes such as older siblings, aunts, or most any woman who might be willing to take charge of the child for a while. During the first two years of life, all sensory-motor development is optimized while, at the same time, all emotional bonds are inhibited. It is probable that the highly impersonal quality of all social relations among adults is owing in a large measure to these early child-training patterns.

That novices chosen for the priesthood must be exposed to a máma's teaching before they reach five years of age plainly refers to the observation that, at that precise stage of development, their cognitive functioning is beginning and that mental images of external events are being formed. If educated within the social context of their families, the child would develop a normative cognitive system, which has to be avoided because the cognitive system of a priest must be very specific and wholly different from that of an average member of society.

As has been said, there are no children's games, that is, there is no rehearsal for future adult behavior. Nothing is left to fantasy, can be solved in fantasy; everything is stark reality and has to be faced as such. And as the child grows up into an adolescent, these precepts are continuously restated and reinforced. The youth must eradicate all emotional attitudes, because nothing must bias his judgment—neither sex, hunger, fear, nor friendship. A man once said categorically: "One never marries the woman one loves!" Moreover, most cultural mechanisms in Kogi behavior are accommodative. The individual has to adapt himself to the reality that surrounds him and cannot pretend to change the world, not even momentarily—not even in his fantasies [better to get 'right with reality']. The concept of yulúka, too, becomes an accommodative tool because it represents an undifferentiated state of absolute unconsciousness.

To exercise spiritual leadership over his society, the priest must be completely detached from its daily give-and-take, and it is evident that separation, isolation, and emotional detachment are among the most important guiding principles of priestly education. This "otherness" of the Kogi priest is expressed in his training in many ways: from his nocturnal habits, which make him "see the world in a different light," to his isolation from society, which makes of him a lonely observer, devoid of all affection.

The Spartan touch in Kogi culture must be understood in its wider historical perspective. During almost one hundred years, from the time of the discovery of the mainland to the early years of the seventeenth century, the Indian population of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta was exposed to the worst aspects of the Spanish conquest. After long battles and persecutions, the chieftains and priests were drawn and quartered, the villages were destroyed, and the maize fields were burned by the invading troops. In few other parts of the Spanish Main did the Conquest take a more violent and destructive form than in the lands surrounding Santa Marta and in the foothills of the neighboring mountains. During the colonial period, the Indians lived in relative peace and isolation and were able to recuperate and reorganize higher up in the mountains. But modern times brought with them new pressures and new forms of violence. Political propaganda, misdirected missionary zeal, the greed of the Creole peasants, the ignorance of the authorities, and the irresponsible stupidity of foreign hippies have made of the Sierra Nevada a Calvary of tragic proportions on which one of the most highly developed aboriginal cultures of South America [or any culture anywhere] is being destroyed. So far the Kogi have withstood the onslaught, thanks mainly to the stature of their priests, but it is with a feeling of despair that one foresees the future of their lonely stand.

Bibliography

Preuss, Konrad Theodor

| 1926-1927 | Forschugsreise su den Kágaba. Beobachtungen. Textaufnahmen und sprach-liche Studien bei einem Indiunerstamme in Kolumbien. Südamerika. 2 vols. St. Gabriel-Mödling: Anthropos Veriag. |

Reichel-Dolmatoff, G.

| 1950 | "Los Kogi: Una tribu indigena de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia," Vol. 1. Revista del Instituto Etnológico Nacional (Bogota) 4:1-320. |

| 1951a | Datos histórica-culturales sobre las tribus do la antigua Governación do Santa Marta. Bogota: Imprenta del Banco do la República. |

| 1951b | Los Kogi: Una tribu indigena do la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Colombia. Vol. 2 Bogota: Editorial Iqueima. |

| 1953 | "Contactos y cambios culturales en la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta." Revista Colombiana do Antropología (Bogota) 1:17-122. |

| 1974 | "Funerary Customs and Religious Symbolism among the Kogi." In Native South Americans—Ethnology of the Least Known Continent. Patricia J. Lyon, ed. Boston/Toronto:Little, Brown. |

The anthropologist's narrative of the Kogi is about all we would have known of them had not the two films, The Elder Brother's Warning and Aluna (filmed by the Kogi) been made. I see no reason to discount any information provided. The work seems credible, a commendable effort, and a worthy offering to value thanks to Younger Brother science. Allowances, however, need to be made for limitations of place and time.

Imagine an apparently unknown group from some remote valley near the China/Tibet border asked a filmmaker to present their concerns to the "Other World" that was threatening their own. It turns out an anthropologist had visited them in the 1950s. Instead of mentioning "Búnkuasé, the shining one," or "the balance of yulúka," the ámams (priests) speak of "Lao Tan, the old boy," and "the harmony of Dao." The anthropologist provides much information of value not revealed in the film, but did not know the people's history.

In the film, the ámam of history mentions that Lao Tan, about 2,500 years before, had come to their valley. He was a critic of Empire, of putative civilization, and some who served the dynastic empire of the time had considered his alternative vision. They wondered why he had left and some considered that they should too. Twelve families decided to go elsewhere to live beyond the reach of empire and its ways. At the border a guard mentioned Lao Tan had preceded them, but that he had stayed long enough to write down some of his insights.

The families followed the clues and came to join Lao Tan who helped them reshape customs, reevaluate all values, and to consider ideas about the structure and functioning of the Universe that molded individual behavior into a plan of actions and avoidances to maintain a viable equilibrium between Man's demands and Nature's resources. To avoid committing empire, to cleave to the Mystic Female, male aggression and drive for acquisitiveness, sexual and material, needed to be moderated to live within limits. Some men would need to be especially trained to know and model Dao so as to guide their brothers. Some ámams were women, but because women are by nature superior—by nature more givers and receivers than takers. In greater harmony with Dao, they did not need to confess, to self-medicate, to engage in ritual offerings, to receive frequent psychotherapy, to practice abstinence, to fast, to moderate their drives, and so most ámams were men needed to help men know their place. Men appear dominant, are indeed prominent, but their society is a de facto matriarchy that values the Yang to their Yin. As the ámams knew, "The Dao that can be spoken of is not the Absolute Dao."

After the film was released, some scholars, unlike the anthropologist or film maker, came to suspect an even higher culture, one that had worked for 2,500 years (unlike all other complex agrarian wayfarers) and that the level of moral, existential, and intellectual attainment was overlooked by most not because it was more advanced than they knew, but more advanced that they could know. A few realized that Younger Brother Consumers, self-taught five-year-olds with machetes, could learn from these people.