.

WEDNESDAY, SEPT. 11, 2019: NOTE TO FILE

Stand on Unguja

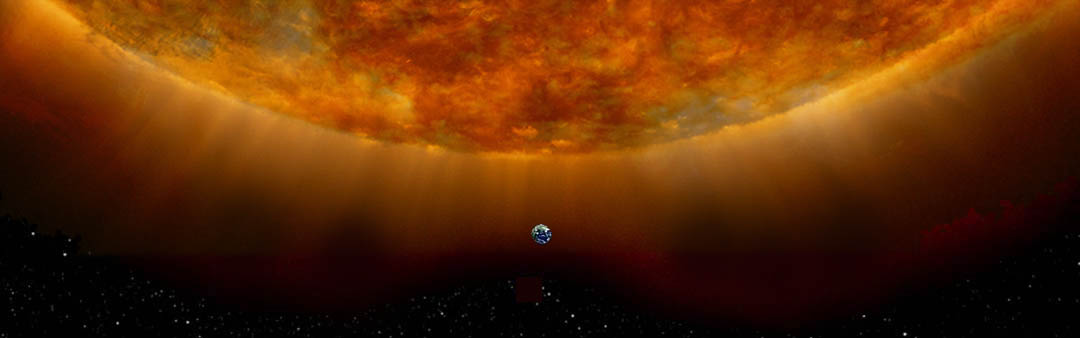

To understand and live properly with the cosmos

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

'Eventually we'll have a human on the planet that really does understand it and can live with it properly. That's the source of my optimism.' —James Lovelock

TOPICS: HOPE, FROM THE WIRES, THINKING IN SYSTEMS

Abstract: A story of the future, of how the best of all possible worlds could come to be.

COOS BAY (A-P) — An entomologist was among the few humans left standing on Earth. The Great Plague had started in North America and its spread was well reported. China, Japan, and NATO had each closely monitored the spread and had flown extensive sorties over the land to confirm the final words from the ground that there were no known survivors in the infected areas. Those infected were highly contagious for up to a week before symptoms, and were dead within 24 hours of the first symptoms. The contagion remained for some unknown time in the environment. There was no time to understand the details.

The plague had begun in a remote area in Mexico where few traveled and none flew such that death occurred so quickly that none sought to flee and thereby unintentionally spread the plague. Once the pattern was noticed, travel, especially by air, was stopped. By the time the plague had reached the first cities, all travel within Mexico had so far as possible ceased and the Federales became evermore Draconian in enforcing the travel ban up to and including summary execution. Soon, all travel in North America had ceased, by fear and intent, the entire force of the US military was used to prevent the spread north. Yet still it spread. All who fled 'away' believed themselves to not be infected. The world ended in belief (denial), not in fire or ice.

The plague had begun in a remote area in Mexico where few traveled and none flew such that death occurred so quickly that none sought to flee and thereby unintentionally spread the plague. Once the pattern was noticed, travel, especially by air, was stopped. By the time the plague had reached the first cities, all travel within Mexico had so far as possible ceased and the Federales became evermore Draconian in enforcing the travel ban up to and including summary execution. Soon, all travel in North America had ceased, by fear and intent, the entire force of the US military was used to prevent the spread north. Yet still it spread. All who fled 'away' believed themselves to not be infected. The world ended in belief (denial), not in fire or ice.

Global military forces outside of North America formed a coalition. Despite the most stringent effort at containment: the shooting down of all planes not doing the shooting, the sinking of all ships attempting to leave the continent, the shooting of all attempting to swim across the Panama Canal, somehow the plague still spread. Africa was the last continent to be spared, but still it came. Those in Tanzania had every reason to think they were the last.

The last ears listening in the last communications outpost in Dodoma, however, had failed to contact those in Zanzibar for technical reasons (the power cable from Dar Es Salaam had failed) and had mistakenly assumed no one there was left standing. When all airwaves went silent, those in Zanzibar, now using emergency generators for a time, had every reason to assume the plague had not reached them yet.

The last ears listening in the last communications outpost in Dodoma, however, had failed to contact those in Zanzibar for technical reasons (the power cable from Dar Es Salaam had failed) and had mistakenly assumed no one there was left standing. When all airwaves went silent, those in Zanzibar, now using emergency generators for a time, had every reason to assume the plague had not reached them yet.

For unknown reasons, it never reached them. But the ending of all imports and exports, the collapse of the financial system, the rapid disappearance of all fossil fuels on the island (save for a few samples a museum curator had thoughtfully stored away), those left standing on Zanzibar Island soon wished the plague had reached the island of 1,121,000 living, for a time, on the 643 square mile (166,536 ha) island (the Coos River watershed, population about 42,000—or 2K to 3K aboriginal—in Oregon is 610 sq. mi., so Zanzibar is of a common watershed/sub-watershed size, but with a population density over 23 times that of the current Coos River watershed which is 17 times the 1750 population prior to the coming of Indo-European plaques).

Offshore financial services were no longer needed and electricity in the power cable from Dar Es Salaam across the waters had stopped flowing, ending the glow at night. The thousands of tourist beds were to remain empty as most left prior to travel bans. Spices and palm thatch were the only agricultural products exported and the only source of food after the shelves were empty was gardens and pastured animals in the countryside. Zanzibar City and other towns on Unguja such as Michenzani, Mbweni, Mangapwani, Chwaka, and Nungwi were rapidly depopulated.

All citizens knew of recent reports of unimaginable horror beyond the shores. All had repeatedly heard that anyone approaching the island by boat or air must be exterminated with extreme prejudice, so none attempted to leave the island. Those attempting to leave the rising urban horrors met resistance from those in the countryside whose gardens promised life but caused the death of many and were mostly destroyed in the scarcity induced conflict.

All citizens knew of recent reports of unimaginable horror beyond the shores. All had repeatedly heard that anyone approaching the island by boat or air must be exterminated with extreme prejudice, so none attempted to leave the island. Those attempting to leave the rising urban horrors met resistance from those in the countryside whose gardens promised life but caused the death of many and were mostly destroyed in the scarcity induced conflict.

A university research station became an enclave of relative calm. Seemingly certain death in a fortnight or so had concentrated some minds wonderfully. Like the Greek scholars who managed to become the émigrés who spread the Greek Learning throughout Europe following events in 1453 Constantinople, some possessed of foresight intelligence had moved to the agricultural experiment station bringing as much food as they could find (along with some of the university security personnel) in the days before shortages arose, to weather the coming chaos.

Of those who had the foresight intelligence to occupy the enclave (0.1 percent or 1,121 of those on the island), scientists were disproportionately represented, but a seeming cross-section of humanity, from poets to one ecolate sex worker seeking unemployment, were represented. The 1,121 brought dependents with them, so the total population within the enclave was 3,828, which was far more than the agricultural productivity the ag station could support long-term (even with the help of the agricultural experts who were running the agroecology research station). Only politicians and activists, those who believed in political solutions, were absent as, of course, they had self-selected out as had the imams who believed in religious salvation.

Word of what was going on about them reached the enclave, but verbal descriptions of the present were not unlike those from the past, and most were not so traumatized as to be unable to think. Plans were made and a brave new future envisioned such as best-guess science could envision. Amid the chaos elsewhere on the island, some approached the research station. The security, in uniform and armed, politely explained that the scientists were working, making superhuman efforts to think well, to come up with real solutions that might work (exactly what they were doing). All went away to seek sustenance elsewhere. No one outside knew or suspected the large amount of food stored on the site, and among those within, some required counseling to accept the decision to not share all with all.

Someone made a plaque that read, 'Nature is unkind.—Laozi'. One political scientist could not bare the inhumanity and went forth to tell the marauding hordes (or 'freedom fighters') that the station contained much food (just barely enough to last four years to enable the enclave's work, for a time, as performed by those who were no longer close to being overweight as 70 percent had been before the plague, including 32 percent who had been clinically obese). He was shot by a security patrol without authorization, but the enclave's leaders merely came, upon reflection, to console the officer who had shot him in the back before he could outrun them. Some minds had become clarified wonderfully.

Someone made a plaque that read, 'Nature is unkind.—Laozi'. One political scientist could not bare the inhumanity and went forth to tell the marauding hordes (or 'freedom fighters') that the station contained much food (just barely enough to last four years to enable the enclave's work, for a time, as performed by those who were no longer close to being overweight as 70 percent had been before the plague, including 32 percent who had been clinically obese). He was shot by a security patrol without authorization, but the enclave's leaders merely came, upon reflection, to console the officer who had shot him in the back before he could outrun them. Some minds had become clarified wonderfully.

The marauding was only for a time. Within months little was heard of such things. Most of those who remained were too busy planting and tending gardens as doing so was indeed, as Candide had surmised, the best of all possible worlds. Soon there was trade. The apparent surplus produce of the station was traded for fish and sea salt. The information those of the station had was offered for free. Knowledge of the size of the enclave's population was not offered at this time.

The good will earned gave members protected passage to the remains of the university to collect books. When out and about, they wore lab coats as a sort of uniform that all recognized and came to respect. The demand for workshops grew and all of the best informed within the enclave took turns traveling by foot in the area near the station, sharing in the sharing economy that self-organized with some helpful direction by the social scientists. They became de facto leaders of villages that self-organized about them as residents valued new ways that worked. Care was taken to ensure no community exceeded 150 members, with most numbering 20 to 80 to promote trust, equitable sharing and cooperation.

While at the city, some had revived HAM radios for a time, but the ether was silent. Maydays on all frequencies went unanswered. Some of the more nerdy managed to set up a bank of scanners, called SEII, and kept them working for months, but no signs of techno-industrial life on Earth was found. The lack of news helped clarify the mind and simplify their understanding of the human problematique.

The team estimated the depopulation event on the island, untouched by plague, to be about 97 percent. There were now perhaps 33,000 living on the island, about one per five hectares, and all of them, except for those in the enclave, thought that surely the island that had supported over 1,120,000 could support the remaining forever and a return to prosperity was around the corner. But the large population, as everywhere else, was only made possible by turning fossil fuels into food and importing food made mostly of fossil fuel from elsewhere.

There was actually about 40,000 ha of agricultural land on Unguja, of which 25,000 was pasture and 13,000 ha was arable (and with 70 inches of annual rainfall, no irrigation required), plus a couple thousand hectares of palm fiber plantations. Some forested areas unsuitable for agriculture remained, but almost all that could be put into production had been and much of what had been was degraded. Without fossil fuel inputs, direct and indirect (e.g. turning natural gas into nitrogen fertilizer via Haber process), land cannot be put into continuous production without fallow periods of up to 25 years. Managed grazing within sustainable limits could support draft animals (slaves) to do some of the work, but animals can turn pasture into food and if the human population is too large, then doing so for a time works. A larger human population than was sustainable or optimal was, for a time, supported, but humans can do the work of producing their own food when highly motivated to do so.

Initially all environmental resources were exploited knowing that doing so could only be for a time. Without changing human behavior to balance human demands on Nature's resources, the expected number of births would be 1,180 per year. To avoid Malthusian deaths, the birth rate was adjusted to 69 births per year island-wide. Initially one in 75 fertile women could have a baby per year. The seemingly few children were given the greatest care and highest education (literate, numerate and ecolate) human endeavor could offer, and they all prospered to iterate towards their fullest potential. Within one lifetime women could expect to have 2.1 children on average. Such were the cold, as judged by the inecolate, equations.

If one arable hectare can support 2.5 people working it, perhaps with a bit of help from animal labor, then assuming maximum production for a time, the remnant population of 33,000 could be supported until soil fertility and yield declined with each planting due to failure to fallow the land or grow green manure crops if possible. Leaving land fallow is always possible. Still, with a very low birth rate of just enough and normal death rate the population would degrow without scarcity induced conflict arising again. Resources could be exploited unsustainably (but knowingly) for a time (and would be). But population degrowth would continue and within a few decades former agricultural lands could be managed for Nature restorancy. In seventy years all could live prosperously on one-fifth of the island while sustainably harvesting abundant oceanic resources from one-fifth of the surrounding sea. The abundance would require only the part-time labor of humans to harvest and of perhaps the few draft animals used on occasion. By not maximizing population by maximizing labor and minimizing consumption there would be time enough for love and learning.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

There was a nice mansion near the station whose owners had been vacationing in Vale. It was palatial and looked so monumental on the hill. The entomologist, E.O. Warume and many of the other newcomers to the station moved in. Without electricity the pumps and UV sterilizer didn't work, and the swimming pool had turned eutrophic. Some chemicals were found that could kill all the algae, but a new guideline had arisen: 'seek out the condition now that will come anyway' and as the chemicals would not last long, why use them? Downspouts were redirected to maintain the water level and no one bothered to lecture the children who swam in it to not pee in it as making the water slightly greener wouldn't matter. They were told, however, to pee in containers so the urine could be used as a fertilizer for use on crops, and so for that reason no one would think to pee in the pool. All had a life-driven purpose to do what worked, and so did and worked without pay. There were no more wage-slaves.

After the first year of frenzied effort and weight loss, most were still alive, but the demands on arable lands, pastures, bush-meat, wild plants, and fish and seaweed were unsustainable. Environmental productivity would descend further and with it the human population (although the last 300 years had appeared, to those prospering for a time within the fossil-fueled pulse, to be an exception as obviously we Anthropocene enthusiasts were ever so much more clever and exceptional than our ancestors). Or population could descend faster than the loss of environmental production with an increase in per capita consumption. The current situation, an island with too many wannabe Anthropocene enthusiasts longing to return to BAU (business-as-usual), was that of a downward spiral in the offing. Rapid population decline was the adaptive response as was re-education.

One 'solution' would be to export excess population off island. That no one beyond the shore seemed to have survived the plague was best-guess interpretation of the evidence that had not been shared. What awaited anyone going beyond the shore to elsewhere was unknown. Whether the plague organism remained, even if no standing humans did, was unknown. But the reason to not export surplus population was that doing so was merely the short-term apparent solution.

A consensus had arisen among the ecolate (systems science literate) of the enclave that only potentially real solutions would be offered and false claims resisted. If some left the island and came back with tales of 'empty land for the taking', then the pattern would merely be repeated and the reckoning as-usual delayed for a time. Better to understand Earth and learn to live with it properly first, then export the new pattern of managed development (growth), along with the understanding that growth is never sustainable and that living within limits was to be embraced with enthusiasm based on foresight intelligence instead of mindlessly perusing the contingencies of short-term self interest (e.g. BAU, cancer cells).

By the third year most of those living in the mansion and the experiment station came to live in nearby communities and work at least part-time as members thereof growing food when not providing other services. The enclave's stored food was limited, so most had to transition. A few doing work of high value remained, and when the stored food ran out, communities came to gift them food and offer services so their research could continue.

The entomologist had noted that the mostly wood mansion had termites and without termite toxins the palace would not last. To seek out the conditions now that would come anyway, the residents moved out to build thatched huts that provided enough shelter and could be sustainably rebuilt as the centuries passed. The huts were understood to be an improvement. When the mansion would falter and fail, how long it would take if not catastrophic, was unknown. Parts could fail first or the monument could collapse with people still living in it. All understood the situation and the mansion became the ruin it was always destined to become along with all the other too-big unmaintainable structures on the island.

To properly manage the commons, to leave room for Nature and her services (formerly known as 'externalities'), the best-guess consensus was that humans and their livestock and pets should live prosperously well within the environmental productivity of twenty percent, a fifth, of the island's land and its shore. Humans could choose the twenty percent they wanted, but not to exploit a single square meter of Nature's four-fifths.

To properly manage the commons, to leave room for Nature and her services (formerly known as 'externalities'), the best-guess consensus was that humans and their livestock and pets should live prosperously well within the environmental productivity of twenty percent, a fifth, of the island's land and its shore. Humans could choose the twenty percent they wanted, but not to exploit a single square meter of Nature's four-fifths.

Such a self-imposed limit seemed initially to be unthinkable given that all agreed there was not enough land and resources to support civilized humans at the level of consumption the consumer society had led them to demand. The proposal initially seemed profoundly, horribly contrary to the business-as-usual pattern/narrative that all and their great-great-grandparents had known and knew no other story to tell (and, indeed, it was foundationally contrary and irreconcilable). Yet living within self-imposed limits based on understanding the world/island system had recently become thinkable and to seem sane compared to the alternative that was in memory still green.

Those who would rather believe than know were the norm, but to those among the ecolate within the enclave, those possessed by belief were an existential threat to humanity, to any prospect of humans ever coming to understand the cosmos and learning to live with it properly. But the what-is was what currently mattered to most and only questionable information and ways that worked, as tested within the experimental station, were offered. For a time the claims of the true believers held little appeal, creating the possibility to denormalize the belief in belief. The old narratives of better and better had failed spectacularly to account for what had happened nor to offer credible alternatives to chaos that might actually work.

Those living near the enclave, who were beneficiaries of information that worked, who listen to those who listened to Nature, came to prosper, to know a prosperity of enough, and the pattern spread. Those opposed to the new ways, such as those groups organized by and around an imam, moved further away from the 'satanic ones'. As word of the new ways spread, others moved closer to replace those who left. But the area managed under enclave 'rules of the game' grew faster than the number of immigrants, so the population density became lower than outside the area.

Within a few years, over half of the people came to live by the enclave's new guidelines and benefit from the information that worked as well as benefiting from medical and educational offerings. All of the communities about the enclave agreed to come to the aid of any community threatened by those who rejected the new ways. The new pattern thus spread until those rejecting enclave guidance and benefits struggled to live on a third of the island. Their population continued to grow by 3.1 percent, despite high childhood mortality, as it had before the plague even as their territory continued to shrink as more of the struggling came to align themselves with the enclave's 'Federation of Communities' model of social and biophysical economic development.

Those living the 'new' life that worked came to agree to new rules, including the one that only those births blessed by the Mothers were allowed. The Mothers were concerned with the prosperity of posterity, of their descendants to the seventh generation and beyond, and so were by nature better able to resist short-term calls for maximizing self interest. They were informed by the best-guess of systems ecologists and population biologists about the environmental productivity of island biomes including the agroecosystems each community depended on and what level of trade would be sustainable. Per capita consumption could be increased and agricultural labor decreased among the overworked, but only by working to restore Nature's productivity and by further reducing the human population. If too many were working too hard on overexploited land and sea, then the number of births the Mothers blessed each year would be reduced.

To leave room for Nature (for the Mother whose nature the Mothers partook of) as known to they whose science was based on listening to Nature as 'giving parent', the Mothers came to envision a transition to taking no more than one-fifth of the island and managing it for posterity. This required a further decrease in population. All could understand that population could only be lowered by increasing the death rate or lowering the birth rate far below the prior 3.6 percent norm (5 births per woman). Those beyond enclave influence came to fight among themselves as all attacks upon enclave member communities were met by a combined force of the citizen militias (known as Guardians) of all enclave communities. A policy emerged that the combined Federation of Communities militia would drive the attackers back and beyond until defeated and their community dispersed, some to go to kindred communities, and the others to remain and become Federation. If all left, then Federation members came to occupy the land. That those becoming Federation prospered more was noted and resistance waned. Some remained outside the Federation, but had to stop attacking Federation member communities, but they ended up over-exploiting their environmental resources and fighting with one another.

The Federation became a de facto matriarchy. Men wore most of the lab coats in the field, talked much about policies and what worked, theorized at length, but all could admit and acknowledge the natural superiority of women as embodied in the Mothers. Their best guess, as informed by the best guess of systems science, was the guiding light. The men might work on a new policy for weeks or months, analyzing it unto paralysis. When run past the Mothers, if they had issues, then the men knew to reconsider and endeavor to think about 'it' better. The Mothers could be wrong, and could come to understand their error when explicated, so they could be challenged and were, but at some point issues come down to best guess and the women, on the whole, were acknowledged to be by nature better aligned with the Mother in their concerns. Our Mother, Nature as in the nature of things (Gaia, Aluna....), selects for what works and has all the answers, so what is your question?

Within the enclave, the first woman to stand with Mother convincingly was Donella Suzumi, who had the only copy of Donella Meadows' Thinking in Systems: A Primer. All came to read or reread the book, and thereby come to iterate towards thinking better in systems, which became the shared language of the ecolate. When Donella Suzumi spoke, the others learned to listen, though she had no letters after her name. She made no apology for having been a sex worker. She had never served industrial society with enthusiasm. Her mien and manner, the clarity of her thought, gave no one even a passing thought of disrespect. Her best guess had led to empowering those Mothers who would rather know than believe, and perhaps to the saving of humankind.

As the millennia passed, the Mothers blessed those who had blessed the community with their service. Thus did there come to be more like unto them. Not all women were suited to be Mothers who would wisely choose the fathers, thus did male atavisms, that empire-building had selected for, come to decrease in frequency.

As conditions in the outlying areas worsened and fragmented in conflict, some communities who had agreed to stop attacking Federation communities went further and came to accept enclave rules and limits, adding their area to that receiving Federation benefits and protection. In less than five hundred years all became voluntary members. Some communities failed. Others served as models of what worked whereby they spread their memes and genes.

In some communities the imams remained in control, but agreed to allow the community's Mothers to bless only such births as were needed to transition to the prosperity other communities enjoyed. Initially there seemed to be few births, far below replacement level. But per best-guess of those who maybe knew enough to have an opinion, the carrying capacity of the island's twenty percent was judged to be 4,500. Thanks to enclave medical services (including birth control and abortion), the death rate was expected to continue to decrease. To maintain a population of 4,500, a further 85 percent reduction in population was needed.

The 'Why?' was patiently explained to anyone wanting to understand why. All evidence-based claims were subject to questioning. The how was by reducing births to the 69 per year needed to maintain the target population assuming life-expectancy increased from the prior 55 years to 65 years with the new health care (as distinct from illness care) system, the best care that could be provided by those trained by enclave medical experts. The few children were given the best ecolate education human endeavor could provide.

Within a decade paper technology had been revived. Many books remained, in various languages, but in time all would pass away. The first edition of Rosetta Bliss was published by human powered press. Within another decade the first edition of Encyclopedia Bliss was published. Only information of high value was printed, and compiling it was the life-driven purpose of the scholars the communities provided with support as all information was offered freely. All communities had a copy of Rosetta Bliss for the studying by those so inclined. Those mastering the visual language as autodidacts could borrow a volume of the encyclopedia for study. Within half a century the enclave became the site of the Academy of Evidence and Reason. Those who managed the commons had self-selected into the position of serving the community by understanding it and the place (Nature) it was of. They were known as Earth Agents, they who listen, listened to Nature who had all the answers. Humans and all else were the 'not-two' which is none other than the 'one'.

Apart from limits that applied equally to all, community rules/norms could and did vary. Some communities failed and their ways went with them. Others prospered more and others paid attention and adapted such ways as worked long-term. Within five hundred years, environmental restoration had nearly come to equal what it may have been before humans had arrived on the island (e.g. slave traders) to build or serve empire. The Zanzibar leopard, thought extinct for 25 years, made a comeback. There were no urban areas and no urbanized humans of NIMH to occupy them. There were 86 prosperous villages on the island and Nature also prospered. There was a central city as a gathering place that was inhabited only during full moons by most, where each maintained a city home. A symphony orchestra self-organized much as it once had in Kinshasa. But living in such complexity was only for a time, so benefits exceeded harm. There was far more resources than needed, and the human, livestock, and pet populations could have been greatly expanded for a time. From childhood on, storytellers told why doing so would be inecolate and recounted stories of 'and then what?' that were not fictionalized in the least as cautionary tales.

It had taken five hundred years for the people of Zanzibar to learn to understand the island system and to live with it properly so as to thereby be blessed by the Great Mother (as metaphor) as they indeed were being blessed. All had enough. Explorers and then settlers came to occupy other islands and the Swahili coast. It was 'empty' of humans, but there was no thought of filling it or of taking more than 20 percent of any watershed to fill with humans, crops, livestock and pets. Instead they sought to occupy a part and to manage it sustainably within limits. The pattern thus spread out of Africa, not unlike a different pattern had before, but this time humans told different stories and did not go fourth as conquerors or takers to become the last hominid standing.

Instead, they went forth as givers, as Earth Agents. It took another five hundred years for humans to sparsely reoccupy the planet, though this time there would never again be a glow of their presence as seen from space. This time we the people understood the place for the first time as humans living in complex societies that worked, and so had learned to live within the cosmos properly. The last place on Earth to be reoccupied were the islands of Malta. Six hundred prosperous people came to live there. Who would have thought the first enclave had not been built on Unguja? Munuko served as its first tour guide when travel by sail again became common.

This time the coming of humans enhanced the process of Nature restorancy. Life on Earth made a more rapid recovery thereby. It would take less than ten million years for biodiversity to be restored, and humans would come to prosper evermore, all 42 million of them who had not only preserved the knowledge and know-how of those who came before, but added information of the highest transformity to thereby enable humans to evolve from so simple a beginning into 'endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful'. They did so in love and understanding, endlessly iterating towards the best of all possible worlds.

In less than a hundred thousand years humans had such technology as would appear as magic to those of the 21st century, but as in all things, it had developed well within the limits of what worked long-term. In space the technology gave raise to the Inquiring Ones who sent back news of the cosmos as they explored the nearby galaxies. From the Inquiring Ones, humans came to know of and be known to the Deep Ones.

Epilogue

Note that if the story seems unbelievable, implausible, unthinkable..., try this: It is heavily skewed towards the positive, the optimistic, towards envisioning the best possible future for humanity and the biosphere imaginable THAT COULD ACTUALLY WORK in terms of the biophysical language that Nature speaks to those who listen. We who may not be so fortunate as to depopulate by plaque could radically reduce births to a target population of 42 million (or an optimum far below a maximum population on one-fifth or less of Earth's land) by storing up grains, during perhaps a 5-10 year transition period, currently fed to livestock (to make meat/eggs/milk) and forming enclaves (aka pockets of sustainability).

No biophysical laws of the cosmos would be violated if some humans, possessed by foresight intelligence as others are by deeply held beliefs, succumb to necessity, to what will come anyway. The transition would take longer than the plague had allowed, one lifetime more, with a goal of none who became Federation would die a Malthusian death and thereby preserve information (our memotype) and those able to live cooperatively in a functional, evolving complex society needed to express memes that work in educated (literate, numerate, ecolate) minds, arguably a better if more complicated future than one involving a Great Plague (or chaotic descent), and so more difficult to envision.

But we the people of the global complex empire-building techno-industrial society won't because we can't. Living rightly is not about choice but about love and understanding. Awake to both and to choiceless awareness. Freedom is the recognition of necessity. At best some, perhaps 0.1 percent or one in a thousand, could vote with their feet to form enclaves of sustainability to iterate towards understanding the world system and learning to live with it properly so as to again become the last hominid standing, but this time memetically one of a different ilk.

But back to the plague solution: digital archaeologists would eventually recover enough information to allow historians to determine that the beneficial consequences of the Great Plague had been unintended despite the evidence that it had been manufactured. To develop a vaccine, the contagion had to be engineered first. The pathogen had, however, escaped confinement before the vaccine had been developed.

The marauding hordes phase will only be for a time. Will it be better if spread out regionally over many decades? 'Seek out the condition now that will come anyway.' Sooner will be better.

It turned out that the people of Zanzibar were not the only humans left on the planet, but only the last complex society to preserve information (and literacy, numeracy and ecolacy). Such few as had survived, such as on cruising sailboats, were mostly unable to successfully form reproductive populations, and those who did, whose descendants met the Unguja explorers, were at the tribal level of pre-chiefdom complexity, though in one region early empire-building had begun where it was supported by agriculture that was in the process of forming chiefdoms that would lead to monument-building that would become ruins. Such 'native' populations were not interfered with (per 'non-interference directive') as the Ungujans were not conquistadors (or Borg). But within five hundred years of first contact, all humans had by mutual agreement become Federation.

Initially overly enthusiastic humans occupied 22,549 watershed management units (WMUs) because they could, but a prosperous life came to be lived within 19,847 WMUs (average population 2,117) the more arable and environmentally rich areas. that selected for what worked, and supported maximum diversity (and maximum empower long-term) such that all of humanity's eggs were not in one complex global society. When most of those living in the more marginal WMUs agreed to abandon their WMU, they emigrated to more prosperous WMUs or remained in their homeland but without reproducing. The WMU was retired and became part of Nature's domain. Rarely a small minority unable to adapt to any existing WMU, spread across thousands of WMUs as solitary misfits, decided to vote with their feet and, with Federation permission, reinhabit an abandon WMU. Most 'mutants', however, were not functional when aggregated together. In one well-known and much studied exceptional case, however, those unable to get along with 'normals', were able to get along with one another and form a functional complex society.

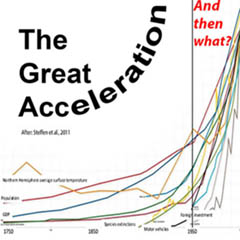

The Federation listened to Nature and defined limitations per best-guess. Initially it had enabled communities (and later watersheds) to self-organize for protection from outlying would-be empire builders, but that essential function passed away. What remained was to iterate towards a collective better understanding of the system, from quantum subsystems on up to cosmos, with special attention to Earth's geobiosphere, and to enforce limits, such as limits to growth to leave room for Nature apart from humans and their crops, livestock, pets, and sprawl. By the end of the first millennia after the Great Acceleration, the ecolate human population had decreased to 31 million who occupied one sixth of Nature's expanse to better leave room for biodiversity and allow more time for each human to love and understand the Earth.

The Federation listened to Nature and defined limitations per best-guess. Initially it had enabled communities (and later watersheds) to self-organize for protection from outlying would-be empire builders, but that essential function passed away. What remained was to iterate towards a collective better understanding of the system, from quantum subsystems on up to cosmos, with special attention to Earth's geobiosphere, and to enforce limits, such as limits to growth to leave room for Nature apart from humans and their crops, livestock, pets, and sprawl. By the end of the first millennia after the Great Acceleration, the ecolate human population had decreased to 31 million who occupied one sixth of Nature's expanse to better leave room for biodiversity and allow more time for each human to love and understand the Earth.

And the best of all possible futures? It may come but not by choice. Humans don't get a vote. Listen to Nature who has all the answers. When the prattle of the believing mind subsides, Mind is clarified wonderfully. 'To seek Mind with the mind is the greatest of all mistakes.'

For those who do not stand on Unguja, there is The Malta Solution, a variation on the Unguja solution.

'Seek out the condition now that will come anyway.' —H.T. Odum