TUESDAY, FEB 26, 2019: NOTE TO FILE

Critical Mass

A film on population issues

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: POPULATION ISSUES, FROM THE WIRES, FILM TRANSCRIPT

Abstract: Feature films considering existential concerns of scientists are as rare as those humans who would rather know than believe. "Doomer" concerns are ignored, marginalized or denied outright. Malthusian doomers are especially reviled. John B. Calhoun and his "rats of NIMH" experiments, which involved putting rats and mice in an arbitrary and unnatural context, is an alternative source of existential concerns for humans in complex techno-industrial societies, aka human zoos. Even if concerns related to energy and material shortages could be dismissed as humans "decouple" from Nature, complex societies may develop increasing complexities that lead to a "behavioral sink" effect and irreversible loss of functional behaviors over the span of less than a dozen generations as pathologies accumulate and lead to extinction.

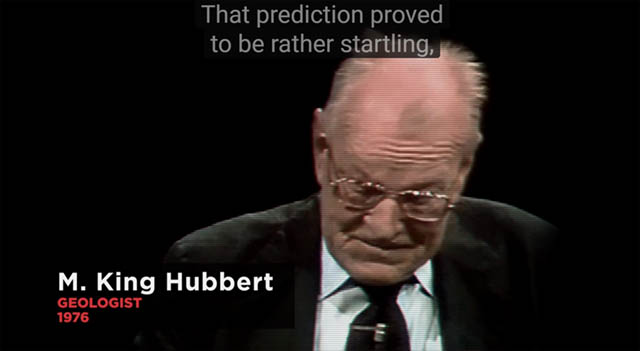

COOS BAY (A-P) — This is a transcript of a feature-length 2012 documentary by Mike Freedman intended for global distribution. About 60 scientists, academics, authors, activists and advisors were interviewed, over 200 hours were compressed to one hour of mostly talking heads, with some musical and visual interludes, with 42 surviving the final cut. It is about population, as in human population as it reaches critical mass. The science of John B. Calhoun is featured, with a supporting cast that includes William Rees, Desmond Morris, Joseph Tainter, Herman Daly, video clips of Norman Borlaug and M. King Hubbert among others.

I had been researching along the lines this film deals with for four years before I chanced to come across mention of it. I'll infer that the film, the only high-quality professional production I know of dealing with existential issues facing humanity, is one that almost no one has seen or heard of. I read one review and an interview, then rented a streaming version to view online which was good for 48 hours. I didn't watch it, knowing that I'd rather read and would need a transcript to vet the content, and as I couldn't find one, I spent about 25 hours with subtitles turned on and audio off stepping through the film a few seconds at a time while I typed. I also captured screen shots of the speakers in an attempt to keep their image matched with their name. Late on the second day my wife, a guest, and I watched it.

I had thought to figure out how to pirate a copy to share the information, all of which the speakers had offered freely, but why bother? The filmmaker should upload the film to Pirate Bay as post-release word-of-mouth increases revenue as some who hear about the film will pay to view (Mike, become a kopimist and upload your film). The film was never distributed. Rotten Tomatoes knows it exists, but there are no reviews. IMDB offers a synopsis and one "user" review. It wasn't even released on DVD. Not because it is not professionally, award-winningly made, but few will find the content entertaining overall, so it ain't got what 99.9+% of humans in industrial society want. This film will never go viral on Facebook, and if mentioned, who would Like or Share it on social media? It was mentioned on Reddit by title only and there were three brief comments with one offering a link to a YouTube video of Calhoun and his Mouse Utopia that is not pay-walled. One blogger reviewed the film, and there is a Stanford associated audio interview of the film maker. And th-th-th-that's all folks! The following YouTube video offers a far better overview of Calhoun's science and concerns (as distinct from politicized interpretations): The Mouse Utopia Experiments.

Still, the information value is high, perhaps priceless. Those reading the transcript are likely to spend $3 to $5 to view it, though I didn't find viewing the film entertaining nor actually informative as there was too much information to process in real time even though most was well plowed material I was familiar with. While the film was shown at seven film festivals and received an award, the content may not be of the sort that enthusiasts share or think about after seeing it. Critical Mass premiered at Biografilm Festival 2012, Italy, and made an appearance at a half dozen other film festivals in 2012 to 2013. One award: Newport Beach Film Festival 2013, Winner: Outstanding Achievement in Filmmaking - Environmental.

None of the thoughts I had had while transcribing arose in the blur of viewing it, though the vintage video of Calhoun and what authors looked like in person that I had only read helped turn them into persons, and so was worth the viewing. The ultimate value of the film may be that some small fraction of the few who view it will be motivated to read the books many of the speakers are associated with/known for or otherwise look into the issues. The issues involved can't be considered in much less than a lifetime. The thoughts of the scientists, who had spent the better part of a life listening to Nature, were of high value. Some presenters, like Hans Rosling, are a distraction, while about half a dozen are part of the problem and should not have been included. Vet the sources, all of them, and all claims made. [Added info/comments in brackets.]

"I [John B. Calhoun] shall largely speak of mice, but my thoughts are on man, on healing, on life and its evolution. Threatening life and evolution are the two deaths, death of the spirit [élan vital, life-driven purposeful behavior of an evolvable subsystem] and death of the body [individual organism]. Evolution, in terms of ancient wisdom, is the acquisition of access to the tree of life. This takes us back to the white first horse [Conquest, the other three being War, Famine, and et al. premature Death (recently joined by the fifth—Misinformation)] of the Apocalypse which with its rider set out to conquer the forces that threaten the spirit [e.g. a viable population/species as viable subsystem] with death.... [empire building, i.e. the modern form of expansionist human, is death by conquest of conquered (both other humans and Nature, e.g. megafauna, resources for the taking), then following a delay, the conquerer dies by dissipation/conquest/overshoot—the first death/extinction of a population/species]."

[Above is intro to Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population, a 1973 article by John B. Calhoun in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Calhoun's concern, why his thoughts were on man, is the understanding that humans are not different in kind from mice ('mere animals'), and that extinction is the pathway modern overdensity living humans are enthusiastically treading. He is forced to speak in religious metaphor as his concerns are on healing our pathological condition, on life and its evolution (posterity's persistence which will involve renormalizing modern humans). His proximal message (as is mine) is to the few who may know enough to understand his concerns for humanity, but his distal message is to humanity, hence the use of metaphor. In all cases the dynamic of overdensity overshoot, his rat and mouse societies, selected for their extinction, which is not a metaphor but a cautionary tale. The condition of not listening has a foreseeable outcome.]

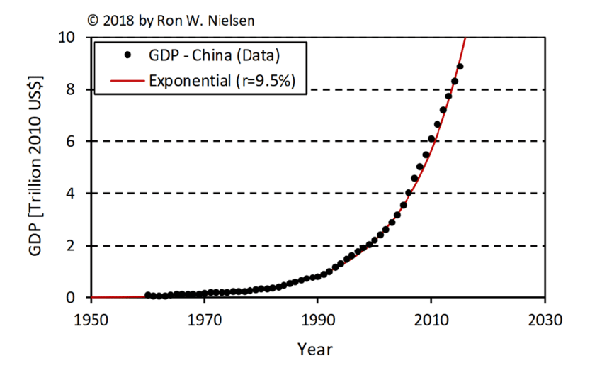

Note: One pixel on high-res monitor = ten years.

In 100 years where will the red line be?

Is 0 billion possible?

How high will it have gone?"Conclusion:" [of Death Squared]

"The results obtained in this study [of Mouse Universe 25] should be obtained when customary causes of mortality become markedly reduced in any species of mammal whose members form social groups [hu-mans, he is talking about you]. Reduction of bodily death (i.e. "the second death') culminates in survival of an excessive number of individuals that have developed the potentiality for occupying the social roles characteristic of the species. Within a few generations all such roles in all physical space available to the species are filled. At this time, the continuing high survival of many individuals to sexual and behavioural maturity culminates in the presence of many young adults capable of involvement in appropriate species-specific activities. However, there are few opportunities for fulfilling these potentialities. In seeking such fulfillment they compete for social role occupancy with the older established members of the community. This competition is so severe that it simultaneously leads to the nearly total breakdown of all normal behaviour by both the contestants and the established adults of both sexes. Normal social organization (i.e. 'the establishment') breaks down, it 'dies'." [i.e. we become humans of NIMH, as we have]

"Young born during such social dissolution are rejected [neglected] by their [self-absorbed] mothers and other adult associates. This early failure of social bonding becomes compounded by interruption of action cycles due to the mechanical interference resulting from the high contact rate [but low repeated contact with the same individuals] among individuals living in a high density population. High contact rate further fragments behaviour as a result of the stochastics [random variable or process] of social interactions which demand that, in order to maximize gratification from social interaction, intensity and duration of social interaction must be reduced in proportion to the degree that the group size exceeds the optimum [of less than Dunbar's number]. Autistic-like creatures, capable only of the most simple behaviours compatible with physiological survival, emerge out of this process. Their spirit has died ('the first death'). They are no longer capable of executing the more complex behaviours compatible with species survival. The species in such settings die." [Interactions exceeding the optimum undermines human ability to trust, see Copykittens and Trust, and play the game/simulation.]

"For an animal so simple as a mouse, the most complex behaviours involve the interrelated set of courtship, maternal care, territorial defense and hierarchical intragroup and intergroup social organization. When behaviours related to these functions fail to mature, there is no development of social organization and no reproduction. As in the case of my study reported above, all members of the population will age and eventually die. The species will die out. "

"For an animal so complex as man, there is no logical reason why a comparable sequence of events should not also lead to species extinction [emphasis added]. If opportunities for role fulfillment fall far short of the demand by those capable of filling roles, and having expectations to do so, only violence and disruption of societal organization can follow. Individuals born under these circumstances will be so out of touch with reality [post-truth?] as to be incapable even of alienation. Their most complex behaviors will become fragmented. Acquisition, creation and utilization of ideas appropriate for life in a post-industrial cultural-conceptual-technological society will have been blocked. Just as biological generativity in the mouse involves this species' most complex behaviours, so does ideational [memetic] generativity for man. Loss of these respective complex behaviours means death of the species."

"Mortality, bodily death = the second death [the normal and necessary death of phenotypes that enables species, genomes, to be evolvable]

Drastic reduction of mortality [births>deaths, resulting in an overshoot population]

= death of the second death [failure to maintain population under carrying capacity, resulting in posterity's death by overshoot debt]

= death squared

= (death)2

(Death)2 leads to dissolution of social organization

= death of the establishment

Death of the establishment leads to spiritual death [loss of viable function]

= loss of capacity to engage in behaviours essential to species survival

= the first death [functional behaviors are a precondition for evolvable life which comes first, so such death is a first death]

Therefore: (Death)2 = the first death. [failure to renormalize, recover capacity to engage in behaviours essential to species survival, is species extinction, first by a loss of functionality followed by bodily death]

Happy is the man who finds wisdom [sapience],

and the man who gains understanding [precondition for memetic/cultural social auto-control limiting human demands on Nature's resources].

Wisdom is a tree of life to those who lay hold of her.

All her paths [towards renormalization] lead to peace [adaptation/persistence].

—(Proverbs iii.13, 18 and 17, rearranged)"]

—John B. Calhoun [Death Squared, 1973]

[To understand something (e.g. system dynamics, death2) is to be delivered from it. —Spinoza]

0:20

Jon Adams, author of "The Rodent Experiments of John B. Calhoun.pdf":

Two and a half years ago we found Dr. John Calhoun knee deep in mice

in the mouse heaven he designed for the National Institute of Mental

Health near Washington. Dr. Calhoun wanted to find out what would

happen to a mouse colony given everything mice need, except living

space. He

built an enclosure, which he calls a rodent universe, in a disused

barn.

0:20

Jon Adams, author of "The Rodent Experiments of John B. Calhoun.pdf":

Two and a half years ago we found Dr. John Calhoun knee deep in mice

in the mouse heaven he designed for the National Institute of Mental

Health near Washington. Dr. Calhoun wanted to find out what would

happen to a mouse colony given everything mice need, except living

space. He

built an enclosure, which he calls a rodent universe, in a disused

barn.

0:35

Cat Calhoun, John B. Calhoun's daughter: I don't know if you've ever

been anywhere where there was a lot of rodents in an enclosed space,

but it's real heavy on the rodent smell. When you came up the stairs

it was just their office area, which I remember as being rather

cramped and, you know, just desks and file cabinets and stuff. And

then you opened the door into the main area. There was a glass

window, observation window, for each of the little mini rooms. So you

could go up the stairs and lie down on the roof and watch the rats

from above, which was fun. [chuckles]

0:35

Cat Calhoun, John B. Calhoun's daughter: I don't know if you've ever

been anywhere where there was a lot of rodents in an enclosed space,

but it's real heavy on the rodent smell. When you came up the stairs

it was just their office area, which I remember as being rather

cramped and, you know, just desks and file cabinets and stuff. And

then you opened the door into the main area. There was a glass

window, observation window, for each of the little mini rooms. So you

could go up the stairs and lie down on the roof and watch the rats

from above, which was fun. [chuckles]

1:11 Jon Adams: He put rats into this enclosure, which was effectively four separate pens. He wanted to control space, to control the ways in which the rats accessed one another, the way in which they would bump into each other.

1:23 NARRATOR, voice of John B Calhoun: No jumper connects pens one and four, therefore there are two end pens and two center pens, two and three.

1:36 Jon Adams: He supplies ample bedding, he supplies ample food, he supplies ample water, and these rats want for nothing.

1:43

Desmond Morris, [zoologist, ethologist and surrealist painter,] author of "The Naked Ape" [and "The

Human Zoo"]: The rat population started to grow. Now in the wild

it would have spread out, or there would have been predators present.

But here there were no predators, and no possibility of spreading

out.

1:43

Desmond Morris, [zoologist, ethologist and surrealist painter,] author of "The Naked Ape" [and "The

Human Zoo"]: The rat population started to grow. Now in the wild

it would have spread out, or there would have been predators present.

But here there were no predators, and no possibility of spreading

out.

1:54 Jon Adams: There's a number of ways in which the way that he sets his experiments up lends themselves to being applied quite easily to the urban situations.

2:04 Desmond Morris: He was creating, essentially, an urban environment for his rats. It was like rat city.

2:10

[William] Bill Rees, population ecologist [co-originator of the "ecological footprint" concept]: They reached a point,

after a given number of doublings in which behavior began to change

radically.

2:10

[William] Bill Rees, population ecologist [co-originator of the "ecological footprint" concept]: They reached a point,

after a given number of doublings in which behavior began to change

radically.

2:16 Jon Adams: And this is where the experiments really get pretty interesting.

2:20 A Day 600 Production. A Mike Freedman Film. Freedman is NARRATOR: Like you, I live in a world filled with other people. It seems impossible to find a place on Earth untouched by human hands. How does this human world affect us? How did we get here, and where are we going?

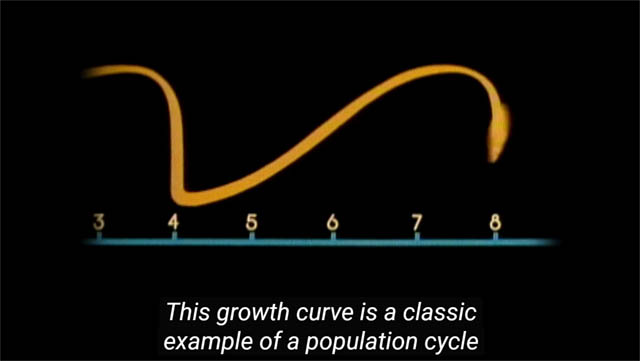

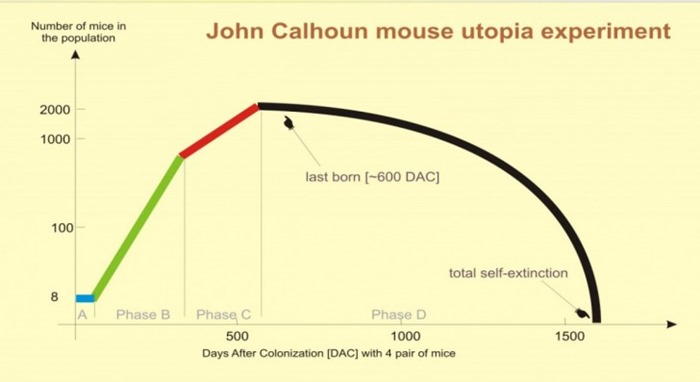

3:06 NARRATOR: As with any story, it's best to begin at the beginning. In this 18-cell mouse habitat, utopian conditions of nutrition, comfort, and housing were provided for a potential population of over 3,000 [3840]mice. The mouse universe simulated the present situation of the continually expanding population of humans.

3:29 Desmond Morris: Human beings evolved as tribal animals living in small groups of maybe 100, 200 individuals. [Tribe: several related bands of 5 to 85 individuals who occasionally met up to exchange genes and memes.]

3:37 William Rees: You might meet 50, perhaps 200 people max, in the course of your lifetime.

3:41

Dennis Fox, critical psychologist [The term critical psychology refers to a variety of approaches that challenge mainstream psychology's assumptions and practices that help sustain unjust political, economic, and other societal structures.]: There was very little competition.

There was very little pressure. If people were getting too close you

could, your group could go someplace else.

3:41

Dennis Fox, critical psychologist [The term critical psychology refers to a variety of approaches that challenge mainstream psychology's assumptions and practices that help sustain unjust political, economic, and other societal structures.]: There was very little competition.

There was very little pressure. If people were getting too close you

could, your group could go someplace else.

3:51

John B. Calhoun [an American ethologist and behavioral researcher noted for his studies of population density and its effects on behavior. He claimed that the bleak effects of overpopulation on rodents were a grim model for the future of the human race]: When the group that's introduced is rather small,

each individual can move around and associate with his physical

environment, and he sort of incorporates them into himself, that

these are part of him, his ego boundaries. This is what I am.

3:51

John B. Calhoun [an American ethologist and behavioral researcher noted for his studies of population density and its effects on behavior. He claimed that the bleak effects of overpopulation on rodents were a grim model for the future of the human race]: When the group that's introduced is rather small,

each individual can move around and associate with his physical

environment, and he sort of incorporates them into himself, that

these are part of him, his ego boundaries. This is what I am.

4:07 NARRATOR: Within the first 100 days the mice went through the period Dr. Calhoun called strive. This was a period of adjustment. Territories were established and nests were made.

4:20 : If a particular tribe was successful it would split off and another tribe would develop, and in that way, we fanned out to cover the whole land surface, pretty well, of the planet.

4:31

Joseph Tainter, professor of environment and society Utah State

University [and author of The Collapse of Complex Societies, societies collapse when their investments in social complexity and their "energy subsidies" reach a point of diminishing marginal returns.]: Hunting and gathering societies have very few parts.

Pretty much everyone follows the same rules and the same occupations.

4:31

Joseph Tainter, professor of environment and society Utah State

University [and author of The Collapse of Complex Societies, societies collapse when their investments in social complexity and their "energy subsidies" reach a point of diminishing marginal returns.]: Hunting and gathering societies have very few parts.

Pretty much everyone follows the same rules and the same occupations.

4:39

Robert Engelman, president, The Worldwatch Institute [former journalist who writes about the environment and population]: There were lots

of reasons that it made more sense for women and men to have similar

interests. You couldn't really move too many people around easily.

4:39

Robert Engelman, president, The Worldwatch Institute [former journalist who writes about the environment and population]: There were lots

of reasons that it made more sense for women and men to have similar

interests. You couldn't really move too many people around easily.

4:46 Fox: We didn't have agriculture, we didn't have possessions. We relied upon each other on a daily basis.

4:54 Calhoun: in the early primitive hunter group they had about 15,000 years to solve their impasse when they were stuck by the carrying capacity of the environment.

5:04 Fox: And then about 10,000 years ago, the story goes, we came up with agriculture.

5:09 : Then we had, for the first time in our long history, a food supply, a food surplus.

5:18 Fox: Agriculture brought with it larger accumulations of people living in one place, the ability to support people who weren't directly engaged in the hunting/gathering, or farming small scale for themselves.

5:36 : This kind of agricultural existence that we had now developed changed our personalities.

5:44 Fox: Because of this accumulation, people were no longer living this egalitarian, carefree existence. There was hard work, possessiveness, and royalty, and poor people, and maybe slaves.

5:59 Engelman: Suddenly relationships between men and women were changing very dramatically, and leaders evolved, hierarchy evolved.

6:06

David Korten, editor, "Yes!" magazine [author, former professor of the Harvard Business School, political activist, prominent critic of corporate globalization, and "by training and inclination a student of psychology and behavioral systems"]: So you get a few

people on the top, you get most people on the bottom, and more and

more of our resources went in to maintaining the system of domination.

[A political, not science-based POV of the what-is.]

6:06

David Korten, editor, "Yes!" magazine [author, former professor of the Harvard Business School, political activist, prominent critic of corporate globalization, and "by training and inclination a student of psychology and behavioral systems"]: So you get a few

people on the top, you get most people on the bottom, and more and

more of our resources went in to maintaining the system of domination.

[A political, not science-based POV of the what-is.]

6:16 Calhoun: This dominant male maintains pen one as his territory, to the near exclusion of all other males. He moves freely about pen one. He examines and enters the artificial burrow which houses his harem of adult females.

6:38: Engelman: More hierarchy, more male leadership, and a clearer idea that women were possessions. They weren't partners, they weren't suddenly fertility goddesses, which we see in the paleolithic. Suddenly they became property for men.

6:51 Joseph Tainter: Hierarchy didn't simply come about because people accepted it, it came about because [the SYSTEM of complex empire-building societies, from chiefdoms to nation-states, selected for hierarchy] circumstances made it necessary, and those circumstances were probably rising populations.

7:02 : Villages grew into towns, and in towns specialists developed. The men making weapons, and jewelry, and clothing, and all kinds of arts and crafts, and scientific developments were occurring in these towns, and the towns grew into great cities. And, although I'm covering 1o,000 years in 10 seconds, that gave us, eventually, the urban world in which we live today.

7:34

Colin Campbell, petroleum geologist [British petroleum geologist who predicted that global oil production would peak by 2007, but fracking has delayed peak oil. He claims the consequences of this are uncertain but drastic, due to the world's dependency on fossil fuels for the vast majority of its energy]: You know, at the time of Christ

the world's population was about 300 million. And the number only

doubled over 17 centuries.

7:34

Colin Campbell, petroleum geologist [British petroleum geologist who predicted that global oil production would peak by 2007, but fracking has delayed peak oil. He claims the consequences of this are uncertain but drastic, due to the world's dependency on fossil fuels for the vast majority of its energy]: You know, at the time of Christ

the world's population was about 300 million. And the number only

doubled over 17 centuries.

7:42 William Rees: 200,000 years to reach a quarter billion people. That's almost zero growth for 99% of the history of our species. Your ancient governments would usually encourage growth of population [as do modern SYSTEMs].

7:55 Joseph Tainter: Food for the cities, sons for the army, taxes for the state.

7:58 Adams: Cities begin to grow. Cities become the place where, through economic necessity, huge numbers of people flock.

8:06 Campbell: The industrial revolution that came in the beginning of the 18th century [1712 Newcomen steam engine], more or less. And coal fired it up in the first place, and then it was followed in mid-19th century by oil.

8:19 William Rees: We've had enormous growth in just the last couple of hundred years.

8:23 Colin Campbell: The population grew, tenfold, more or less in parallel with oil.

8:27 Robert Rapier, author of "Power Plays" [works in the energy industry and writes and speaks about issues involving energy and the environment. He is Chief Technology Officer and Executive Vice President at Merica International, a forestry and renewable energy company involved in a variety of projects around the world]: We've had the agricultural [Green] revolution on the back of cheap oil. I think the role of cheap oil has been understated in the explosion in the food production that we've had.

8:36 Campbell: Oil provides an enormous flood of easy energy. The equivalent of billions of slaves [about 100 slaves per person in industrial society] working round the clock, you could say. They're approaching population densities the likes of which humanity's never seen, and it's getting worse.

8:50 Joseph Tainter: A higher population density means that a society has to be more complex, simply to integrate the large number of people.

8:58 Adams: There's this increasingly urgent problem of how do you house all the people which are now moving to the cities.

9:03

Gary Marcus, author of "Kluge" [scientist, author, and entrepreneur. His research focuses on natural and artificial intelligence. Marcus is a Professor in the Department of Psychology at New York University and was Founder and CEO of Geometric Intelligence, a machine learning company later acquired by Uber]: A kludge to a clumsy or

inelegant solution to a problem. You can think MacGyver, or duct tape

and rubber bands. Something that gets the job done, but not

necessarily in the most efficient or elegant fashion that you can

possibly imagine. They start building tower blocks, into which you

can stack more people.

9:03

Gary Marcus, author of "Kluge" [scientist, author, and entrepreneur. His research focuses on natural and artificial intelligence. Marcus is a Professor in the Department of Psychology at New York University and was Founder and CEO of Geometric Intelligence, a machine learning company later acquired by Uber]: A kludge to a clumsy or

inelegant solution to a problem. You can think MacGyver, or duct tape

and rubber bands. Something that gets the job done, but not

necessarily in the most efficient or elegant fashion that you can

possibly imagine. They start building tower blocks, into which you

can stack more people.

9:18 Adams: So you start seeing the first skyscrapers. The cities grow, in terms of sheer population numbers, they grow up, and so when a city's growing out a little bit it gets denser, and denser at the inner core.

9:28

Paul C. Sutton, professor of geography, University of Denver [teaches geographic statistics, population geography, and ecological economics]: They

talk about these using the language of the beehive. Hives where you

can pack a great number of people and they'll live together, very

much in the manner of bees, cooperating, being productive.

9:28

Paul C. Sutton, professor of geography, University of Denver [teaches geographic statistics, population geography, and ecological economics]: They

talk about these using the language of the beehive. Hives where you

can pack a great number of people and they'll live together, very

much in the manner of bees, cooperating, being productive.

9:41 Adams: Many people mistakenly think that this is indicative of humanity's decoupling from Nature. What could possibly go wrong?

9:49

John Michael Greer, author of "The Wealth of Nature" [writes on the environment, various religions, and occult topics. He served from December 2003 to December 2015 as the Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and since then has focused on the Druidical Order of the Golden Dawn, which he founded in 2013]: The

basic driver of all these problems is the attempt to have infinite

economic growth on a finite planet.

9:49

John Michael Greer, author of "The Wealth of Nature" [writes on the environment, various religions, and occult topics. He served from December 2003 to December 2015 as the Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and since then has focused on the Druidical Order of the Golden Dawn, which he founded in 2013]: The

basic driver of all these problems is the attempt to have infinite

economic growth on a finite planet.

9:56 William Rees: This is a grotesque error, one that we'll rue in the long run.

10:03

Wolfgang Pekny, founder, Platform Footprint Austria [activist . His main topics include biodiversity , commons , international law and life cycle assessments . Between 1975 and 1987 he studied chemistry and biology at the University of Vienna . In 2007, he founded the website www.footprint.at after having co-ordinated the strategic direction of Greenpeace- Austria for about 20 years . Since its inception (about 2006), he has been the chairman of the civil society initiative . In addition, since 2009, he has headed the management consultancy footprint-consult eU]: We have very

successfully conquered our planet, and by conquering the planet we

met at the other end.

10:03

Wolfgang Pekny, founder, Platform Footprint Austria [activist . His main topics include biodiversity , commons , international law and life cycle assessments . Between 1975 and 1987 he studied chemistry and biology at the University of Vienna . In 2007, he founded the website www.footprint.at after having co-ordinated the strategic direction of Greenpeace- Austria for about 20 years . Since its inception (about 2006), he has been the chairman of the civil society initiative . In addition, since 2009, he has headed the management consultancy footprint-consult eU]: We have very

successfully conquered our planet, and by conquering the planet we

met at the other end.

10:12 NARRATOR: It's a pretty impressive picture. The next period lasted about 250 days. The population of the mice doubled every 60 days. This was called the exploit period. When I [Freedman] was born, there were 3 billion people in the world.

10:40

Hans Rosling, [Swedish MD and amateur statistic enthusiast, former]

professor of International Health, Karolinska Institute [co-founder and chairman of the Gapminder Foundation, which developed the Trendalyzer software system. He held presentations around the world, including several TED Talks in which he promoted the use of data to explore development issues]: This Lego

block represents 1 billion people.

10:40

Hans Rosling, [Swedish MD and amateur statistic enthusiast, former]

professor of International Health, Karolinska Institute [co-founder and chairman of the Gapminder Foundation, which developed the Trendalyzer software system. He held presentations around the world, including several TED Talks in which he promoted the use of data to explore development issues]: This Lego

block represents 1 billion people.

10:44

Herman Daly, former senior economist, World Bank [Before joining the World Bank, Daly was a Research Associate at Yale University, and Alumni Professor of Economics at Louisiana State University. As Senior Economist in the Environment Department of the World Bank he helped to develop policy guidelines related to sustainable development. While there, he was engaged in environmental operations work in Latin America. He is closely associated with theories of a steady-state economy. He was a co-founder and associate editor of the journal, Ecological Economics]: World population

has tripled in my lifetime, and I don't think that's ever going to

happen again, at least I hope it doesn't.

10:44

Herman Daly, former senior economist, World Bank [Before joining the World Bank, Daly was a Research Associate at Yale University, and Alumni Professor of Economics at Louisiana State University. As Senior Economist in the Environment Department of the World Bank he helped to develop policy guidelines related to sustainable development. While there, he was engaged in environmental operations work in Latin America. He is closely associated with theories of a steady-state economy. He was a co-founder and associate editor of the journal, Ecological Economics]: World population

has tripled in my lifetime, and I don't think that's ever going to

happen again, at least I hope it doesn't.

10:51 Rosling: When our teacher told us we are 3 billion people, she said that the Indian population and Chinese population will grow to become 1 billion, but everyone understands that that's impossible. Yeah, that's impossible, everyone said [not everyone]. We told our parents, they'd say, of course that's impossible, they will starve to death, that won't happen ["they" didn't foresee the Green Revolution].

11:09 NARRATOR: My grandfather was born in New York City, in 1914. In the previous 100 years the world's population had grown from 1 billion to 1.6 billion. Since my grandfather was born the world's population has gone from 1.6 billion to more than 7 billion. Slowly the indicator crept up the grandest grand total in the history of the United States, and there it was [200 billion]. "The signs show the dramatic increase [4 million USA population in 1790, 50 million in 1880, 100 million in 1915, 200 million in 1967] of America's population in under 200 years, and experts reckon that at the current rate of birth acceleration a 300 million total is possible by the turn of the [twentieth century."

11:49 NARRATOR: My grandparents had two children, my father and uncle. My father had three children, my uncle had four. My brother and sister each have one child. So from my two grandparents 100 years ago there are 11 people alive today. This is called the exponential function.

12:39 "Somewhere on this globe, every ten seconds, there is a woman giving birth to a child. She must be found and stopped." Sam Levenson 1911-1980

12:44

Jeffrey McKee, professor of anthropology, Ohio State University [physical anthropologist conducting research on hominid evolution and paleoecology]: It

hits that exponential growth, and then up until the industrial

revolution it keeps on going up and up and up. But with the

industrial revolution, the rate itself increases even more. And so we

go from something like, you know, a growth of 0.02% to a growth of

2%.

12:44

Jeffrey McKee, professor of anthropology, Ohio State University [physical anthropologist conducting research on hominid evolution and paleoecology]: It

hits that exponential growth, and then up until the industrial

revolution it keeps on going up and up and up. But with the

industrial revolution, the rate itself increases even more. And so we

go from something like, you know, a growth of 0.02% to a growth of

2%.

13:00 Rosling: Look 4 billion people more in the world, and at the same time industrialized countries, they grow much richer. And these 4 billion extra landed somewhere here, and 1 billion of them were very successful [consumers]. The emerging economy, the top of the emerging economy. We noted it in Sweden this year because China acquired the Volvo company.

13:22 NARRATOR: In 1971, the world's population growth rate peaked at 2.1%. In 2011, the growth rate was 1.2%. It seems like the population of the world is growing slower than it was, but in 1971, the world's population was just under 4 billion. A growth rate of 2.1% meant that 79 million new people were born that year. In 2011, the growth rate was 1.2%, but there are so many more people in the world that the number of new people born each year is almost the same [77 million]. new people are born every minute, 8,850 every hour, 212,000 every day. That adds up to 77 million a year. By the end of this film, there will be 15,000 more people in the world than there are now.

14:06 NARRATOR: But they couldn't care less what the figure is or will be. That's for the grownups to worry about. His main concern is not millions of mouths to be fed. Just one, his.

14:19 William Rees: The demographers missed the baby boom after World War II, and they [chuckles], they got ridiculed a bit for that. And so they've kind of stepped back from this idea of making predictions and they make projections. And there's usually a high, and a medium, which is sort of what they expect, and a low projection of what future population scenarios are.

14:39 Rosling: Population keeps growing while family size shrink, and the growth only stops 30 years after a country have hit two children per woman, because they are building up the middle age people and the old people in the population.

14:55 NARRATOR: Population growth is measured and projected using something called the total fertility rate, or TFR.

14:59 José Miguel Guzman, Population and Development Branch United Nations Population Fund [contribution to the understanding of population issues and their relevance for national policies and programmes. Contribution to demographic studies and to the improvement of public policy in the social domain spans several decades and covers a variety of issues, borne out in a publication list of more than 20 books and 50 articles]: The total fertility rate is just the number of children that women have in all their reproductive life. Let's say, from the beginning she'll start having children, to the end.

15:08 NARRATOR: The TFR for a stable world population is 2.33 children per woman. This is called replacement rate. High income countries, upper middle income countries, lower middle income countries, and low income countries.

15:21 Rosling: This pile [Legos] here have two children per woman. Two children per woman here, and also here. Vietnam, Mexico, Bangladesh, down to almost two children per woman. So this means that in just one or two decades more the population growth will stop here. The problem we have with population growth is entirely here in the two poorest billion. There is not vaccination for all children, so children are dying. So people have good reasons of getting many children. [Rosling's narrative leads to the popular and acceptable (to Anthropocene enthusiasts) view that more equitable economic growth and per ca-pita consumption, aka "progress," must continue, sustainably of course.]

15:48 Calhoun: Looking back at the historical record, and certain insights from mammals of the kind which man traces his lineage, had led to a conclusion that the optimum world population is 9 billion.

16:05 William Rees: They say 9 billion by 2050, and this is sort of UN estimates, and the UN has historically underestimated where we're going to, so we may be at more than 9 billion by 2050 [if we can keep on keeping on]. I don't think anybody thinks that's a good idea.

16:22 Rosling: Up to 2050 we cannot avoid another addition of 2 billions, but what will happen with these ones? I have no doubt that they will catch up here. That means more energy use, more consumption.

16:36 NARRATOR: In 2011, the world's TFR was 2.46 with a population of over 7 billion people. The UN population division projects that we can expect 9.3 billion people on the planet by 2050. That medium projection relies on the world's TFR falling to 2.02, a drop of 18%. At replacement level, 2.33, their high projection is almost 12 billion in 40 years, if we bring fertility rates down by 6%.

17:05

Martha Madison Campbell, public health lecturer, University of California at Berkeley [long been interested in world population growth, women’s empowerment, and issues of scale. With Dr. Ndola Prata and Potts she published in 2012 “The Impact of Freedom on Fertility Decline,” their paradigm explaining the slowing of population growth in a human rights framework. Has written and presented on the widespread silence about the population subject since the 1990s, and the costly results around it]: If women have, on

average, 2.1 children you could end up with that 9 billion people out

to the year 2300, but if you add just a third of a child more you end

up with 36 billion people by 2300. That is the power of compound

interest, if you will.

17:05

Martha Madison Campbell, public health lecturer, University of California at Berkeley [long been interested in world population growth, women’s empowerment, and issues of scale. With Dr. Ndola Prata and Potts she published in 2012 “The Impact of Freedom on Fertility Decline,” their paradigm explaining the slowing of population growth in a human rights framework. Has written and presented on the widespread silence about the population subject since the 1990s, and the costly results around it]: If women have, on

average, 2.1 children you could end up with that 9 billion people out

to the year 2300, but if you add just a third of a child more you end

up with 36 billion people by 2300. That is the power of compound

interest, if you will.

17:23 Rosling: These 3 billions, which is like Vietnam today, Peru today, they want to move here. Here we will get 2 billion extra. If these ones remain in poverty when we reach 2050, then they will continue to grow. But if they get access to school, health care, family planning, perhaps an electric bulb, yes, in their home, they will also get two child families, and then in 2050, we can stop at 9 billion.

17:54 NARRATOR: The third period, consisting of 300 days, found a population of mice leveling off. This was called the equilibrium period.

18:03 Rosling: And there’s nothing we can do about this 9 billion if we’re not going to kill people at a scale that hasn’t happened in modern history, and I’m talking about centuries, and thousands of years. We have to plan for 9 billion. And don’t think that people should live in poverty, because then they will continue to grow, and don’t even think that people who have a bicycle don’t want washing machines.

18:26 NARRATOR: And how are we doing with the 7 billion people we have now?

18:33

Peter Gleick, academician, International Water Academy [scientist working on issues related to the environment. He works at the Pacific Institute in Oakland, California, which he co-founded in 1987. In 2003 he was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship for his work on water resources]: Badly.

[chuckles]

18:33

Peter Gleick, academician, International Water Academy [scientist working on issues related to the environment. He works at the Pacific Institute in Oakland, California, which he co-founded in 1987. In 2003 he was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship for his work on water resources]: Badly.

[chuckles]

18:37 NARRATOR: At this time, some unusual behavior became noticeable.

18:47 Calhoun: In order to consider physical space and the crowding together, you cannot separate it from the ability to deal with the social organization.

18:52 Cat Calhoun: If you’ve watched these animals in the wild, and studied them, which he had, you know what their normal behavior is. You know how they normally react. You can tell whether what they’re doing there is normal or not, how much it deviates from the norm, and as the population grows you can see the changes.

19:14 William Rees: Desmond Morris, I think, was one to make the point that we actually don’t know how humans behave in nature because we haven’t been in nature for as long as we’ve been making these kinds of records, right? Cities are abnormal phenomena, in the sense that for 99% of human history they haven’t existed.

19:29 Adams: There was this sense out there that people already had, that if you crowd mammals together, they’ll behave aggressively. That people in crowded environments will become more violent, will become stressed.

INTERVIEWER: God almighty. Sorry man, please, we’re filming. Can, no, please. I’m sorry man, that’s in shot. Thanks. How long you gonna be? Intelligibility’s on the door, we’re here till five.

19:56 Calhoun: This is his bubble, and when another mouse comes into that boundary, then it’s as if he was hit physically. His anxiety builds up. It may be an overt fight, as a reflection of the stress of this individual’s space bubble being invaded. One rarely sees more than one rat at a time eating or drinking. As the breeding population reaches a certain level of density, he starts noticing aberrant behaviors.

20:28 : It reached a point where they could no longer function as rats.

20:33 Calhoun: In the center pens, two and three, rats frequently drink beside each other, as they do here in pen three at the lower left. Note how this female comes over to drink beside another, as do these two males. The act of drinking becomes associated with the presence of others.

20:56 Adams: He starts noticing something called pathological togetherness. Despite the fact there’s plenty of food hoppers and water bottles available, all the rats will congregate around one of them. They won’t spread out and keep themselves to themselves. They start displaying these really unnatural and peculiar responses. Human beings evolved living in huge areas, as a tribe of say 60, or big tribe, 200 people.

21:21 : When I looked then at the population of London, or New York, I realized that the population density of our species had increased by 100,000 times since our original tribal life. And it was that tribal life, that was where we evolved, and that’s how our personality was formed.

21:42 Calhoun: The mice have programs, they’re like little computers, and this is basically genetic with a much smaller element of learned behavior. And too high a contact rate disorganizes the program so that it gets washed out, so it’s disconnected, so it doesn’t express itself.

22:06

Edward Hall, anthropologist on old video [remembered for developing the concept of proxemics and exploring cultural and social cohesion, and describing how people behave and react in different types of culturally defined personal space. Hall was an influential colleague of Marshall McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller]: Well, that’s one of

the consequences of overcrowding is that there are, you break action

chains, and the very simple example is a woman goes to the, leaves

her apartment going to the grocery store, or to the drug store with

certain things in mind that she’s going to buy. She gets too

many interruptions of the wrong type, she’s going to forget what

she went to buy, and if she gets enough of them she’s likely to

forget that she was even going to go to the store. And all life is

made up of action chains. Some of them are incredibly complex.

22:06

Edward Hall, anthropologist on old video [remembered for developing the concept of proxemics and exploring cultural and social cohesion, and describing how people behave and react in different types of culturally defined personal space. Hall was an influential colleague of Marshall McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller]: Well, that’s one of

the consequences of overcrowding is that there are, you break action

chains, and the very simple example is a woman goes to the, leaves

her apartment going to the grocery store, or to the drug store with

certain things in mind that she’s going to buy. She gets too

many interruptions of the wrong type, she’s going to forget what

she went to buy, and if she gets enough of them she’s likely to

forget that she was even going to go to the store. And all life is

made up of action chains. Some of them are incredibly complex.

22:34 : You imagine going down the street, and saying “Good morning, hello, how are you,” to every person you passed. It would be crazy. It would be a ridiculous situation. So what we do is we make all but our little tribe [Dunbar’s number] into non-people, and we’re able to continue as tribesmen, which is how we evolved, within the super tribe of the city, and that’s what enables us to survive in these huge conglomerations.

23:23 NARRATOR: Each animal became less aware of associates, despite all animals being pushed closer together. Dr. Calhoun concluded that the mice could not effectively deal with the repeated contact of so many individuals.

23:38 : There are people who say it was a concrete jungle, but jungles aren’t like that. This was a zoo where we’re kept in small cages in this urban environment.

23:46 William Rees: It’s probably fair to say that we are inherently maladapted to the large kind of urban landscapes in which most people live today. Something about the urban environment is changing the way that people behave. One of the theories at the time is that there’s a miasma effect.

24:05 Adams: When you bring all these people together, not only do they become a vector for one another’s diseases, and of course you have epidemics of cholera, typhoid in cities, but also they become a vector for one another’s vices.

24:16 Calhoun: After being attacked, this socially withdrawn male 29, makes a pan sexual approach to male 16, who he recently saw attacked. Note how one assumes the female role.

24:31 Adams: Males exhibit sexual behavior towards other males, you have rat homosexuality, they begin mounting the young.

24:40 Calhoun: Associated with his social withdrawal, his pan sexual mounting of juvenile male.

24:47 Adams: Gangs of males will attack a single female, mounting her repeatedly.

24:52 Calhoun: Here, male 78, forcefully grasps estrus female 123, and hold on. I call these frog mount. They may last minutes, rather than the normal one to three seconds. Females occasionally exhibit pan sexual behavior. Here female 47 attempts to mount dominant male 35, who resents her approaches. Though living with many males she rarely conceived.

25:28 Adams: Here is an animal which doesn’t have a society in the sense that people do, and nonetheless seems to be behaving in the way that people do when they’re in cities. It’s 1962, there’s increasing concerns with overpopulation. There’s concerns, in particular, with urban decay.

25:50 NARRATOR: Newark, New Jersey, became a city of race riots, violence, looting, and hate. For five days it was a battleground and a looter’s paradise. Similar riots in other American centers with hatred near danger point between white and black extremist groups.

26:08 Adams: Journalists and writers, fiction writers in particular, see this as a consequence of the mass of people. Which is to say, it’s not just that there were more people, and therefore there was more crime. Something was happening in the cities that was changing the way people behaved.

26:24 Joseph Tainter: Complex societies have many different kinds of parts. We have many kinds of technologies, we have many social roles and institutions. People specialize in these roles, people specialize in occupations.

26:37 NARRATOR: Dr. Calhoun noticed that the newer generations of young were inhibited. Since most space was already socially defined violence became prevalent. The males on the floor here who are withdrawn, they are highly stressed animals. But the stress comes from each other because of this peculiar violence that they exhibit which leaves them as this animal, with his tail all chewed up, but they do it to each other. These are highly stressed individuals.

27:11 Adams: As the chaos within these enclosures becomes more and more pronounced you’ll have rats which move away from the group, set up on a little perch by themselves all day and only come down to feed at night or when there’s no one else around. Increasingly even this becomes difficult to do. He calls it social autism.

27:30 Calhoun: The way that man differs is that he learned something early, very early in his beginning cultural history, and this was to develop new roles.

27:45 Joseph Tainter: This is what we mean by complexity. An increasing number of parts, and an organization to make those parts work together as a society.

27:53 Calhoun: And in this way the population can increase, the number of people in a particular area, provided you can develop codes that say how, how you operate in the social contract so that you interact with these people and not those people.

28:11 Cat Calhoun: He died before the internet, and before social networking, and blogging, and all of that.

28:19 NARRATOR: In an interview in 1970, Dr. Calhoun said, “Very shortly the entire world population will be bound together into a single, complete information network…. It will require developing new information prosthesis to link these people’s brains to a common pool of information, as well as to each other. Computers are only the beginning.”

28:40 Cat Calhoun: People have created their own little worlds, and decided who gets to be part of them, and how they relate, and what their role in all those little worlds are. And all of the gaming that goes on online where people get on and game, and they take on a persona, and interact under that persona.

29:02 : That’s the ability I have as a human being. I can spend an hour and a half as the hero of a movie because I have the ability of symbolic thought. I can make myself into that hero and enjoy his escapades, and suffer when he suffers, and so on, and so a movie is nothing but symbolic thinking writ large.

29:23 Calhoun: A new kind of space, a conceptualist world of ideas, and progressive development of ideas.

29:31 NARRATOR: So almost the real world is full, so the leftover people inhabit a virtual world.

29:35 Cat Calhoun: Yeah, and they can create new roles in that virtual world. When somebody creates a website, they’re creating a role for themselves, independent of what society may be giving them as a role.

29:54 NARRATOR: Since 2010, for the first time in history, more than half of the world’s population lives in urban areas. Most of us live in towns and cities. Certainly in rich countries, but also, increasingly, in poor countries as well.

30:06

Jeanette Longfield, co-ordinator, Sustain Alliance for Better Food

and Farming [Sustain advocates food and agriculture policies and practices in UK that enhance the health and welfare of people and animals, improve the working and living environment, promote equity and enrich society and culture.]: When you live in a town or a city, generally speaking,

you don’t grow your own food, and in rich countries, to be

honest, you have to go back generations now to get to anybody in my

family or your family who actually was a farmer. We have literally

lost our roots.

30:06

Jeanette Longfield, co-ordinator, Sustain Alliance for Better Food

and Farming [Sustain advocates food and agriculture policies and practices in UK that enhance the health and welfare of people and animals, improve the working and living environment, promote equity and enrich society and culture.]: When you live in a town or a city, generally speaking,

you don’t grow your own food, and in rich countries, to be

honest, you have to go back generations now to get to anybody in my

family or your family who actually was a farmer. We have literally

lost our roots.

30:24 William Rees: We’ve completely physically displaced people from the ecosystems that support them, and that has been accompanied by a psychological displacement. People no longer have any real sense, that I had as a child, of being part of the planet, of being deeply connected to the Earth.

30:38 Longfield: Once you’ve cut yourself off from the food and farming system you forget how valuable it is, you forget how important it is.

31:15 Sutton: If you have a city that’s this much pavement, inside that city there’s a lot of people doing things that require space outside the city to support their life. This much forest area to absorb the CO2 that’s being emitted, this much crop area to produce the food for all the people that are living in that paved area. This much pavement still requires a massive amount of land outside of it to support the people that are living on the pavement.

32:32 Gary Marcus: It’s always made sense for animals to eat whatever food they could get the minute that they could get it, because they couldn’t plan for the future. Now we have grocery stores that are open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and we still have that hunger, and we still go ahead and eat far more than we need to because our brains were calibrated to an earlier era where food was not as widely available.

32:54 NARRATOR: So man millions, but only one Earth. Each man’s need is that of his neighbor, for all there is to share is the wealth of the world. The Wealth of the World.

33:12 William Rees: If you take any population, could be an individual population of a city, or a whole country, the ecological footprint is simply a measure of the total area of productive land and water ecosystems needed to produce the resources that that population consumes, and to assimilate the wastes that are associated with that consumption process.

33:33 McKee: If you were to take the entire human population as it exists today, of, well nearly 7 billion people, and spread people out across the land surface area of the Earth evenly, then every individual would have a certain amount of space. That space turns out to be approximately the size of this stadium. That’s the area in which you have to grow your food, put your residence, have your recreational facilities.

33:57 Herman Daly: Economics is about scarcity, so if something is not scarce, it kind of falls out of economics. And so as long as we were living in a basically empty world, that is empty of us, and our stuff, and full of other things, then we could probably get away with just leaving resources out of the picture because they were super abundant.

34:22

Mathis Wackernagel, President Global Footprint Network [sustainability advocate. Global Footprint Network, an international sustainability think tank. The think-tank is a non-profit that focuses on developing and promoting metrics for sustainability. After earning a degree in mechanical engineering from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, he completed his Ph.D. in community and regional planning at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada in 1994. There, as his doctoral dissertation under Professor William Rees, he created with Professor Rees the ecological footprint concept and developed the methodology]: When I was

born in 1962, humanity used about half the planet’s capacity.

Today we are using at least 40% more than what Earth can regenerate,

so what humanity uses in one year it takes the biosphere one year and

four to five months to regenerate.

34:22

Mathis Wackernagel, President Global Footprint Network [sustainability advocate. Global Footprint Network, an international sustainability think tank. The think-tank is a non-profit that focuses on developing and promoting metrics for sustainability. After earning a degree in mechanical engineering from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, he completed his Ph.D. in community and regional planning at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada in 1994. There, as his doctoral dissertation under Professor William Rees, he created with Professor Rees the ecological footprint concept and developed the methodology]: When I was

born in 1962, humanity used about half the planet’s capacity.

Today we are using at least 40% more than what Earth can regenerate,

so what humanity uses in one year it takes the biosphere one year and

four to five months to regenerate.

34:41 Herman Daly: What’s the fish catch limited by today? Is it limited by fishing boats and fishermen? No, we’ve got too many fishing boats, more than we need. It’s limited by the remaining fish and their capacity to reproduce. So it’s the natural resource which in the full world has become the limiting factor.

35:01 Joseph Tainter: Someone was talking about conservation there, to which Charlie said, “If you don’t use the oil, someone in China will be happy to use it.” [Charles A.S. Hall? Good guess. I emailed Charlie who replied: "I have said that (classic HT. Odum), and I know Tainter well, so it must be me...."] And he’s right. What's the point of conservation? Unless the whole world signs onto it, what’s the point? China’s not going to sign onto it.

35:25 NARRATOR: And that’s the tragedy of the commons right there. That is a kind of tragedy of the commons, yeah. The Tragedy of the Commons [a 1968 essay by Garrett Hardin, human ecologist]. Imagine a pasture where any shepherd can bring his sheep to graze. The pasture is an open access resource, free for any member of the public to use. One shepherd realizes that if he brings more sheep than anyone else, he can benefit from using more of the pasture at no extra cost [other than as shared by all]. He can bring as many sheep as he likes, whenever he likes, giving him a short-term profit. If he didn’t, somebody else would, right? In the end, the pasture is destroyed by overuse, and everyone suffers the consequences. [And the very clever shepherd, having taken the full range of neo-classical economic classes at Oxford, having full foresight of the consequences, did what he had to do, then invest his profits in BP and then Apple to live in unimaginable luxury until his medical team failed to extend his life any further, despite blood infusions from virgins, though his body was cryogenically frozen.]

36:09 Herman Daly: We have open access resources. They really are scarce.

36:14

Fred Pearce, author of “When the Rivers Run Dry” [author and journalist based in London. He is a science writer, reporting on the environment, popular science and development issues from 64 countries over the past 20 years. He specialises in global environmental issues, including water and climate change]: Nobody

has an individual incentive to grab less, because we all share in the

downside in the end, so we kind of rush to disaster.

36:14

Fred Pearce, author of “When the Rivers Run Dry” [author and journalist based in London. He is a science writer, reporting on the environment, popular science and development issues from 64 countries over the past 20 years. He specialises in global environmental issues, including water and climate change]: Nobody

has an individual incentive to grab less, because we all share in the

downside in the end, so we kind of rush to disaster.

36:26 Gleick: The environment, especially, requires government regulation, and government oversight, because without government regulation and government oversight, the environment suffers. And when the environment suffers, the truth is, we all suffer [but only after all, including the homeless living on the street, prosperously consume planetary resources unsustainably].

36:40 Dennis Fox: We already have governments, and things are falling apart. And so, the idea that you have to have government rule in order to keep things from falling apart, I think, historically, it goes the other direction.

36:53 Pearce: Perhaps you have to privatize things in some way if you’re dealing with land, so people can have control over part of this once common resource. The tragedy that Garrett Hardin described didn’t actually happen historically. Those commons were self sustaining, that the people involved did agree among themselves on regulations, and enforce those regulations. And the commons, the commons eventually got destroyed because outside forces came in and took the land away, and that was the end of the commons.

37:21 Greer: Now it has been pointed out, and I think quite rightly, that there are, that traditionally common systems do work because there are social or political controls that keep people from exploiting the commons. But when you get rid of those [controls] as we have in the United States, for example, you end up in a real mess. We are in the tragedy of the commons because we’ve set up an economy whereby all the benefits go to individuals, but all the costs are dumped on society [are commonized. Garrett Hardin regretted not giving his essay the title of “The Tragedy of the Unmanaged Commons”]

37:52 NARRATOR: A land of dark and primitive contrast. Plenty and scarcity. Richness and poverty. Here lived Africa’s peoples, buried in their jungle, too backward to realize the inheritance it offered, the untapped resources of their vast continent. Human need crying in the wilderness. The only answer, the magic of the witch doctor, superstition, age old fears, recurring plague. In Africa, in its jungles, and in its villages, wealth lay wasting [as it had everywhere on the planet before industrial society came to extract it].

38:37

Ann Cotton, president, Camfed [Campaign for Female Education, is an entrepreneur and philanthropist who was awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2006 Queen's New Year Honours List. The honour was in recognition of her services to education of young women in rural Africa as the founder of Camfed]: You

know, the birth right of African children is being sold. And it’s

being sold internationally. Governments are selling land, and they’re

selling resources. They’re partly, of course, being sold

because they need to invest in their health systems, in their

education systems. So they’re in a kind of viscous cycle.

38:37

Ann Cotton, president, Camfed [Campaign for Female Education, is an entrepreneur and philanthropist who was awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2006 Queen's New Year Honours List. The honour was in recognition of her services to education of young women in rural Africa as the founder of Camfed]: You

know, the birth right of African children is being sold. And it’s

being sold internationally. Governments are selling land, and they’re

selling resources. They’re partly, of course, being sold

because they need to invest in their health systems, in their

education systems. So they’re in a kind of viscous cycle.

38:57 Korten, magazine editor: They’re inviting in those foreign corporations to own and control their resources, and to set their economic priorities. So pretty soon you find that your whole economy is designed and operated, not to meet the needs of your own people [just like all other economies fail to do as that isn’t what economic success selects for].

39:13 Cotton: They’re selling on 99-year leases. Land that has historically provided cattle grazing, land that has historically provided local maize. Land that has given community security.

39:28 Korten: But it is also then the advice that the countries get that say, well, the way to grow your economy and maximize your wealth is to organize your resources for export.

39:41 Longfield: Other people will grow our food for us. We’re so rich we’ll just be able to buy it from them.

39:45 Korten: This new form of colonization, which is very clearly the colonization of essentially everybody, by a small elite class that controls these corporate institutions [that are controlled by the contingencies of short-term profit/benefit as any CEO who fails to deliver the goods is soon replaced].

39:57 Cotton: This is a really rather terrifying fact. And that land is, in many cases, lying fallow.

40:04 Korten: One of the things that just stunned me when I was working in Asia, in development, was to hear economists saying, well, you know, don’t worry about your agricultural sector, that’s, in an advanced country, that’s a very small piece of GDP. Use that land for its higher-value use, like a golf course, or a housing development, or a shopping mall, or an export processing zone, or whatever. But, you know, you’re just wasting it on agriculture. Now they were telling everybody that. So then you ask, well who’s going to grow the food? And it’s, you know, it’s part of this disconnect from reality. Whereas, you say, well, whatever percentage food is of GDP, I still need to eat. [chuckles]

40:57

Ian Lowe, president, Australian Conservation Foundation [authored or co-authored 10 books, 10 Open University books, more than 50 book chapters and over 500 other publications. He wrote for 13 years a regular column for New Scientist and also writes for several other publications, as well as contributing frequently to electronic media programs]: It’s a

common economic delusion that as long as the price is right you will

always get what you need. I think Paul Aleck said that economists

would not worry if they were in a bus going over a cliff because they

would be confident that the sudden market demand for parachutes would

generate a supply before they hit the bottom. Economists simply don’t

believe in limits. They believe that if the price is high enough

there will always be a solution.

40:57

Ian Lowe, president, Australian Conservation Foundation [authored or co-authored 10 books, 10 Open University books, more than 50 book chapters and over 500 other publications. He wrote for 13 years a regular column for New Scientist and also writes for several other publications, as well as contributing frequently to electronic media programs]: It’s a

common economic delusion that as long as the price is right you will

always get what you need. I think Paul Aleck said that economists

would not worry if they were in a bus going over a cliff because they

would be confident that the sudden market demand for parachutes would

generate a supply before they hit the bottom. Economists simply don’t

believe in limits. They believe that if the price is high enough

there will always be a solution.

41:24 Pekny: We can eat down the food chain, but we cannot eat recipes.

41:28 Cotton: We are already short of food, but we will become more and more short of food. So those with the means are buying up, are ensuring against the loss of food.

41:40 NARRATOR: In July 2008, the government of Madagascar agreed to give half of the country’s farmland to a subsidiary of the Daewoo Corporation of South Korea, for free, for 99 years. Daewoo announced plans to export maize and palm oil. A manager at the company said, “Food can be a weapon in this world… We can either export the harvests to other countries, or ship them back to Korea in case of a food crisis.” In March, 2009, the government of Madagascar was overthrown by a coup d’etat and replaced. The new government canceled the deal saying that it was in violation of Madagascar’s constitution. In response, Madagascar was suspended from the African Union, and had foreign aid withheld by the World Bank for over two years.

42:26 Duncan Pollard, Director of Conservation Practice & Policy WWF International: If everyone was to aspire to a western-style diet, and the average western-style diet is an Italian diet, both in terms of the number calories, and the amount of meat that’s consumed, there isn’t enough land on the planet to feed everybody. Whether that’s 8 billion, or 9 billion, or 10 billion. It doesn’t matter, there isn’t enough land.

42:45 Pearce: You know, there are people arguing that there is enough food to go around in the world, the problem is the way it’s distributed. And I forget the ratio, but how many people you could feed with the grain that goes into making one Big Mac, but it’s a lot of people.

42:58 Lowe: The world now produces about two kilograms of food, per person, per day. So if it was shared equally each person would have each day about a kilogram of fruit and vegetables, about half a kilogram of cereals and pulses, and about half a kilogram of protein, in the form of meat or fish, or eggs. Now, it would take a pretty good trencherman to get their jaws around two kilograms of food a day. And even in the rich parts of the world people don’t consume at that level.

43:28 Longfield: The reason why people starve in a country, in a world that has enough food, is because they don’t have the money or the power to buy it.

43:37 Pearce: We have a globe where some parties have much more power than others, and some parties have much more power to regulate, and to determine the rules that they want others to live by.

43:48 Lowe: If we distribute food through a market it means that dogs and cats in the United States of America eat better than peasants in poor parts of the world.

43:56 Longfield: It’s not about the food in the long term, it’s about money, and it’s about power. No rich person ever starved. [Food is about energy, the only energy humans needed in the environment they evolved in. Money follows energy flows in reverse direction. Energy is the precondition for and basis of real wealth. Money was unknown to pre-anthropocene enthusiasts. No poor person ever died of over-consumption, so embrace a voluntary poverty of just enough.]

44:04 NARRATOR: The use of resources became unequal. Although each living unit was identical in structure and opportunities, more food and water was consumed in some areas. In 2011, 20% of the world’s people consumed 80% of the world’s resources, leaving 20% of the world’s resources for 80% of the world’s people. [as measured by money that the upper 20% have virtually all of].

44:27 William Rees: One thing that differentiates us from Calhoun’s experiments as I recall them is that there was never a resource scarcity.

44:36 NARRATOR: In 1970, a scientist named Norman Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize for his ongoing work to increase food production around the world. Using pioneering techniques of genetic modification, Borlaug designed strains of wheat, corn, and rice, which fed over a billion people worldwide. The Green Revolution, as it was called, is hailed even today as the triumph of man over the limits of nature. Worldwide, we’ve doubled the amount of crops that we grow over the last 40 years. We needed to, because world population doubled. But we are taking three times more water out of our rivers to do it.

45:14 Gleick: Water’s basically a renewable resource. The river flow we see today, no matter how much we use today, is going to come back in rainfall tomorrow, and we’re going to get more river flow. But there are peak limits to even a renewable resource. We can’t use more water than a river naturally provides.

45:32 Pearce: Now you may think about how much you drink, or how much water you use to flush the toilet, but the real demands on water around the world for you to get through your day are food and drink, and perhaps for growing cotton for your clothing. I worked out my water footprint. It is 100 times my own weight in water every day. That’s what’s needed to get me through my life. And you imagine that among 7 billion people. That’s a huge demand on nature’s water cycle.

46:36

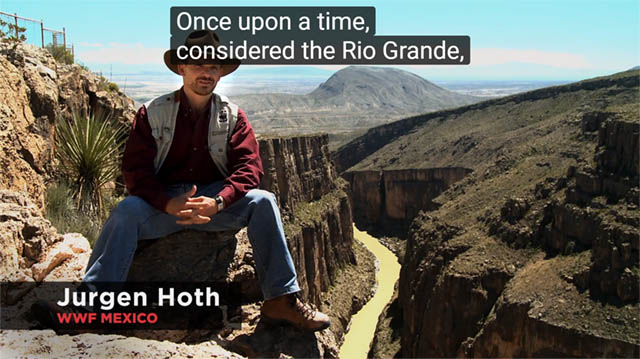

Jurgen Hoth, WWF Mexico [working on soil and water conservation in natural areas from central Mexico]: Once upon a time, considered the Rio Grande,

or Rio Bravo, which means brave, means violent, and nowadays it’s

tame and it’s small.

46:36

Jurgen Hoth, WWF Mexico [working on soil and water conservation in natural areas from central Mexico]: Once upon a time, considered the Rio Grande,

or Rio Bravo, which means brave, means violent, and nowadays it’s

tame and it’s small.

48:49 Pearce: Northern China, the Yellow River doesn’t reach the sea in anything other than tiny amounts. Central Asia, running out of water.

46:54

Chris Goodall, author of “How to Live a Low Carbon Life” [English businessman, author on new energy technologies]:

The Aral sea will dry up. The Nile no longer reaches the

Mediterranean Sea. The Colorado, like the Nile, like the Yellow, no

longer reaches the mouth.

46:54

Chris Goodall, author of “How to Live a Low Carbon Life” [English businessman, author on new energy technologies]:

The Aral sea will dry up. The Nile no longer reaches the

Mediterranean Sea. The Colorado, like the Nile, like the Yellow, no

longer reaches the mouth.

47:06 Pearce: You go to Pakistan, the river Indus, another great river, being completely dried up for much of the year because all the water is being taken out to grow crops.

47:16