SATURDAY, MAR 2, 2015: NOTE TO FILE

Alternative Farming

Non-fossil-fuel based food production

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: ALTERNATIVE FARMING PRACTICE , FROM THE WIRES, NON-FOSSIL FUEL, REALITY-BASED, SURVIVAL ISSUES

Abstract: Organic farming and permaculture, along with agroecology offerings, are widely viewed as alternative to conventional agriculture. They are alternative, but per hectare production will be lower. Without any fossil-fuel inputs, direct or indirect, into an agricultural system, yields will be much lower and all farming will be "organic" like it used to be, but not necessarily with the added benefits of belief-based claims (also see Feng Shui Science Education).

TUCSON (A-P) — First define:

Organic farming: “Organic agriculture is an

ecological production management system that promotes and enhances

biodiversity, biological cycles and soil biological activity. It is

based on minimal use of off-farm inputs and on management practices

that restore, maintain and enhance ecological harmony."

Permaculture: "Permaculture is a philosophy of working with, rather than against nature; of protracted and thoughtful observation rather than protracted and thoughtless labor; and of looking at plants and animals in all their functions, rather than treating any area as a single product system."

Feng shui: “A system of laws governing spatial arrangement and orientation, for positioning a building and the objects within a building, in relation to the flow of energy (qi), patterns of yin and yang, and whose favorable or unfavorable effects are taken into account to bring success, health, and happiness.”

The concept cluster of "organic farming" arose in the 1940's and flourished in the post 1960's era as the belief system was embraced by many with a counter culture inclination. The demand for "organic" is now big business and a well entrenched preference in many hearts and minds. The current organic agriculture production system is specialized to serve a niche market of consumers who can and prefer to pay for the increased production costs. Currently only agrochemical fertilizers and biocides are excluded, which results in organic yields of individual crops that are on average 80% of conventional yields with evidence that the gap would likely increase if organic production were upscaled (a meta-data analysis of 362 studies, but another meta-analysis of 205 comparisons found only a 9 percent decrease on average; Nature found a 5 percent gap for some crops down to a 34 percent (76% of conventional or about 80% average) lower organic methods yield "when the conventional and organic systems are most comparable"), so about 80% compared to straight out no-inputs-spared conventional agriculture that currently "feeds the world".

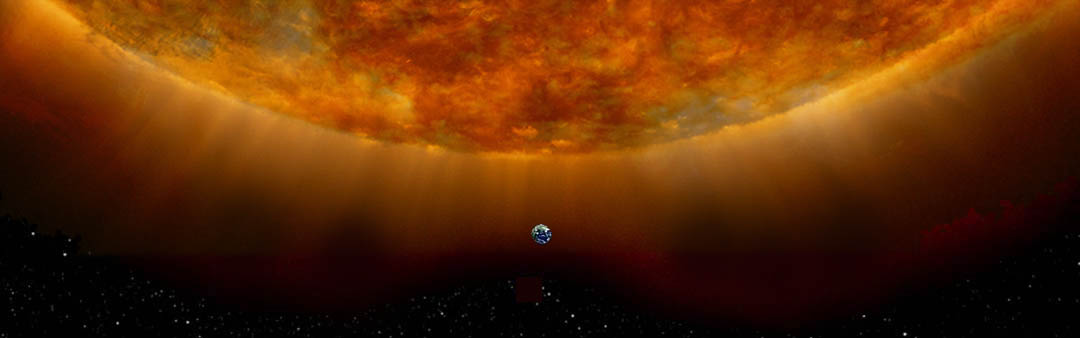

Sources such as the Rodale Institute offer conclusion-driven research results that if correct do not scale up. "Energy blind" research (as the Odums note) is used to support the conclusion that organic agriculture produces as much or more than conventional poison-based agriculture. In a world without fossil fuel inputs, will the agroecological food production systems output be one fifth to one fifteenth what it is today? I don't know, but one tenth may be optimistic, and if humans transition to low intensity gardening/gathering biophysical economies that do not serve elite interests and empire-building society that selects for maximum populations, then one hundredth to one thousandth is a better guess. (Can the planet sustainably support a population of 80 million prosperous humans without degrading Earth's life-support system including its ability to support a pre-Anthropocene level of species diversity? I doubt it. If all environmental productivity were maximally exploited by humans, including maximal conversion of land/water for solar-based agroecoloical production, could Earth support 800 million? Maybe, but 80 million is actually too many if humans are to leave room for Nature, i.e. not cause the extinction of other species or prevent maximum species diversity. Perhaps 8 million people, who view a mania for more that causes species extinction as pathological, would make for a better world for humans and other species.)

Apart from industrial fertilizers (e.g. Haber nitrogen or mined) and biocides, "organic" farming allows all other direct and indirect fossil fuel inputs, which are not viewed as toxins, to be used to be turned into food. Without fossil-fuel inputs (e.g. to draw-down aquifers), vast areas will not be farmable and production per hectare in such dryland farming areas as allow agriculture will not be productive each year as green manure crops and fallow years ranging from 1 to 50 years will be required for sustainable production (e.g. swidden with maybe a 15-25 year fallow period, land in flood plains with annual flooding, rice paddy production with "night soil" and animal manure inputs in water).

In the past eighty years the increase in the rate of food production (of turning fossil fuel into food) has been greater than population growth, which Malthus failed to foresee. The Ehrlichs (the ag experts they consulted) failed in 1968 to foresee the Green Revolution which selected cultivars that could thrive in the environment that fossil-fueled industrial agriculture could create (for a time). Without industrial inputs, the Green Revolution crops will not be used and heirloom crops will, so in areas that currently produce over 200 bushels/acre of corn/maize, good farmers may again get 20-25 bushels/acre average yield for 1-2 years on cleared land followed by 15-25 year fallow period on rainwatered land, or where alternative energy is available it can be turned into food, but not anywhere near on the scale that fossil fuels allowed for a time (for corn as an example, figure 20 bushels/year x 2 years every 20 years, or 2 bushels/year vs 200 bushels/year when fossil fuels were turned into food, for a time), and electricity is of higher transformity, too high to be turned into food, as there may be too little to support information technology). To "seek out the condition now that will come anyway", rapidly degrow the population via managed descent. Create pockets of sustainability within which the fertility rate is dramatically reduced initially, regions where individuals with foresight intelligence can self-select into. See Watershed Design Principles.

A variant conceptology emerged and a new word, "permaculture," was coined in 1978 (and copyrighted), which has served as a locus for a meme system that has spread globally since. The ideas behind "organic" are basic and easy to take in, so "organic" has greater popular appeal. The concepts behind "permaculture" are much denser (may include Odum diagrams as terminology) and require reading books and attending workshops to cover basics, so permaculture is popular with the better educated and more trendy segment of the consumer society.

I am interested in alternatives to fossil fuel-based agribusiness production systems. I do not, however, speak "organic" nor "permaculture" (nor Feng shui). I understand the appeal of the concepts offered to homeowners and small-scale producers of produce for local markets. No one is producing "inorganic" foods (or bragging about it), so the alternative concepts are near universals. A few producers, especially larger scale ones, may only be interested in making money by meeting demand, and could care less about "alternative" practices, but they tend to go along with the expected practices so as to use a premium "organic" name (part of the cost of doing business). Most people, however, who are into alternative production systems buy into the belief systems that explain and promote them. Most people do not realize that there are alternative ways to understand "alternative farming" practices.

Since most off-farm inputs represent embedded fossil fuel inputs into the production system, I eschew them on non-sustainability grounds, whether "organic" or "inorganic," so my cultural practices may be indistinguishable from those of some organic farms. Farming using animal power has been done, but much of a region's farm produce must be used to produce the food to feed the animals. I do not use animal labor, other than chickens and ducks for pest control/weeding. Farming using only human power involves hard work no matter how much time is spent in protracted and thoughtful observation. Alternative to animal power, including human, would be solar powered farm-bots smarter than your average animal. Until farm-bots are available, if ever (don't count on it), to do the heavy lifting, humans will need to. Science and technology can be our friends (or enemies).

The evidence is that "what works" in non-fossil-fueled agriculture involves small villages of up to 75-150 (< Dunbar's number) cooperating to operate diversified farming communities that include processing of agricultural products. So a one family farm that only produces blueberries isn't what works best if at all. A larger labor pool where each may wear multiple hats at different times as needed is what works. The community, in so far as it can, will grow, process, and feed itself, plus produce such surplus for needed trade items and services as environmental productivity provides, sharing imports equitably within fairly narrow limits (0.8:1 to 1.2:1). We all don't have to become Hutterites, Amish, or Kogi, but community-based agriculture works if managed properly. But how many urbanites could live like Hutterites or Kogi if they would? Not living in an agricultural community may not always be possible when what works short term doesn't anymore, e.g. fossil-fueled industrial agriculture. Alternative communities that may help former urbanites recover as products of a "behavioral sink" social environment have been envisioned, e.g. Ted Trainer's The Simpler Way: Envisioning a Prosperous Descent communities.

The only alternative to belief-based ways of knowing is evidence-based ways of knowing. Belief-based systems start with conclusions and cite evidence to support the conclusions. The alternative is to start with evidence and form tentative conclusions or concepts based on the evidence. The difference is fundamental (an epistemological one), and each represent two "universes of discourse" between which communication is limited. Those having an evidence-based way of knowing, know where I'm coming from, and others may not want to know, so nothing more to say.

Eric

PS: So wrong again. I do happen to have something more to say by way of clarifying. If all is clear, then for Athena's sake, stop reading.

In the marketplace of ideas, permaculture may be the oversold commodity it appears to be, so buyer beware. Permaculture speak sounds very sciency, deeply philosophical, and ever so feel goody. It is very scientistic in that many claims and concepts are gleaned from science. In the sustainability/transition universe of discourse, permaculturists tend to position themselves as having the answer, as being the end point of the transition.

The question is not whether permaculture practices work, but do they work better, worse, or as well as other ways? A clear impression is given that permaculture is unquestionably better. Compared to industrial agriculture, permaculture is clearly more sustainable, but factoring in human/animal labor inputs (eMergy) it will not be nearly as productive. Compared to traditional farming practices, without the fossil fuel based inputs, permaculture design and know-how may be assumed to translate into higher productivity, but any such assumption would be belief-based and not evidence-based.

In the New Guinea highlands, traditional farmers have been growing crops for 8,500 years. Imagine that in the Angabanga watershed the Korowai shaman had a vision that all must leave and all did. Neighboring tribes did not move in and the government decided to auction off the entire watershed to the highest bidder. A group of the world's top permaculturists, led by David Holmgren, were high bidders and with their families they moved to their new home. Neighboring tribes invited them to visit anytime and were willing to freely share their know-how and provide seeds and cuttings.

Would the Permaculture tribe:

- Use their vast knowledge and insights to produce 10x more than was thought by neighboring tribes to be possible? [no]

- Produce 5x more? [no]

- Produce 2x more? [no]

- Produce 10% more? [maybe]

- Manage to grow 90% as much? [maybe]

- Would their grandchildren, who intermarried with local tribes, manage to grow as much? [likely]

The most likely outcome would be that their great-grandchildren's farming practices would be virtually indistinguishable from that of neighboring tribes, but when asked to explain why they did what they did, they would answer in fluent permaculture speak, and some would write books.

So what would a know-nothing agronomist do? If I had to move to the Angabanga watershed and could take others, I'd attempt to round up the best agronomists/agroecology grad students (to confess, I have degrees in both crop and soil science), maybe throw in an anthropologist or two, and armed only with our vast collective knowledge (but no industrial inputs), off we'd go. The first thing we'd do (and as all would agree, there'd be no Agronomy tribal chief telling us what to do—there are less than 150 of us) is go to neighboring tribes and closely observe their cultural practices, ask lots of questions, profusely thank them for their seeds and cuttings, and attempt to slavishly do as they did. Our goal would be to produce 90% as much as they did per capita. We would likely fail the first year, but soon we'd be doing well enough. We'd then draw upon our vast knowledge and guess as to what might work better. Then we'd test, setting up an ag experiment station. Most experiments would fail, but we'd expand upon what did work. In only one generation we might be at 105% of native production.

To

think that we could do better than natives with 8,500 years of

experience, would seem like off the scale hubris. But we would have

several hundred years of science on our minds to add to native know-how,

and we'd have the methods of science to learn more. As agronomists with

all the fossil fuel and industrial inputs we asked for, we could

produce 10x more than the natives. Without, we'd be doing unbelievably

well, perhaps in only a few generations, to produce slightly more than

the average tribe. And, yes, I'd stick my neck out and say the Agonomy

tribe would do better (slightly) than the Permaculture tribe.

A Hopi farmer, like his Puebloan predecessors, is able to produce maybe 4 bushels of corn per acre dryland in an area that gets an average of 9.9 inches of rainfall per year. American industrial corn farmers produce about 170 bushels of corn per acre average. Could I, by unleashing the dogs of fossil-fueled agribusiness, produce 170 bu/ac? No; I'd grow more because I'm above average. Could I go to the Hopi Nation, and given only a digging stick, a field, seeds, and such rain as may fall, grow as much as the most incompetent, lazy Hopi farmer? Not the slightest chance. Would "protracted and thoughtful observation" help? Only if spent watching a Hopi farmer. I'd see what worked and my science would allow me to understand or guess why and what might work better. After maybe ten years of learning by listening and doing, I'd consider doing things differently. I'd guess then test, and maybe come up with some cultural change in practice that improved productivity or reduced energy (human power) inputs that the other farmers would consider trying. If I managed to increase productivity by 0.1%, that would be a major achievement, even if posterity knew nothing of it or me.