TUESDAY, SEPT 15, 2020: NOTE TO FILE

The Storytelling Animal

That believe their own stories

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: UNBELIEVEABLE, FROM THE WIRES, SAY IT IS NOT SO

Abstract: Telling tales some mortals have dared to dream before.

COOS BAY (A-P) — That humans are the storytelling animal (Homo s. sapiens var. narrator) is a story humans do not like as evidenced by how few tell the story. David Suzuki once noted in a public talk, as an aside, that humans were animals (i.e. not plants) and was taken aback by the audience pushback during the Q & A. That humans are 'not mere animals' is a verity most would agree could be chiseled in stone if it were not so obvious as to not need to be stated. If the educated must admit that humans are animals (in some technical sense), we humans are obviously different IN KIND from all other animals.

B.F. Skinner noted that humans do differ from other animals in terms of the complexity of their verbal behavior, which is not a difference in kind, compared to, say, rats or corvids. Some dolphins, however, in captivity have learned over a hundred human words. Humans have learned zero Dolphinese. All members of the intelligentsia in Twelfth Century Europe affirmed that God is in Heaven and Kings (and aristocracy) rule by Divine Right. Today all agree that Skinner was wrong (Chomsky was of course right), and any assistant professor could explain at book length why humans are exceptional (even if some don't think so). That pundits are delusional storytellers who don't know enough to have an opinion would not be part of their story.

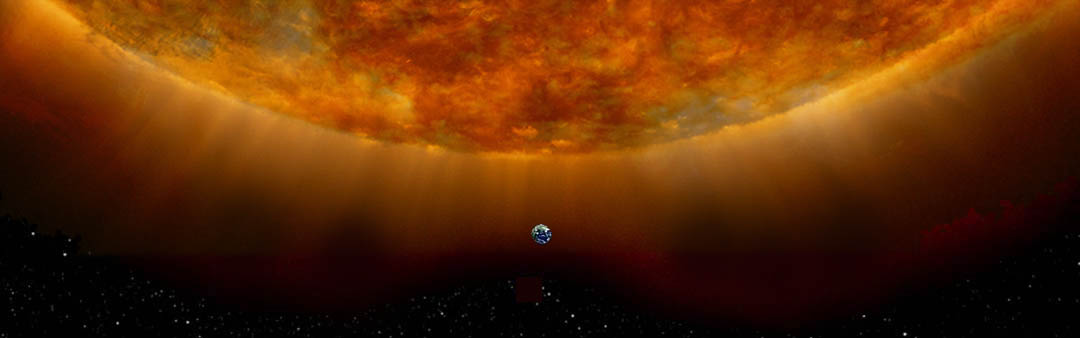

Some corvids and cetaceans may be storytelling animals, but humans may be the only storytelling animal who believes their stories are true, i.e. who mistake their stories about the What-May-(Or-May-Not)-Be for the unknowable what-is (the system which is not only more complex than we know, but is more complex than we can know). But pathologies within complex systems, which includes the verbal behavior of concept forming minds, are not a difference in kind as error, ignorance, and illusion are best understood as such, rather than be elevated to divine verities and received truths (e.g. God, democracy, human rights).

We know nothing, but may iterate towards knowing, towards telling likely stories. Are humans the only animal who suffer from system disorders? No. Will Nature select against dysfunctional behaviors? Yes, as that is what defines maladaptive. What works, works, and our opinion about what works or should work (or why) does not determine outcome. What doesn't work tends to become not part of life on Earth. Disease works, but a pathogen that killed one hundred percent of an obligate host would only flourish for a time. Is Earth's biosphere an obligate host for technoindustrial humans?

In your opinion, do you think Nature cares what your opinion is? QED.

'Many people are startled to learn that most of what they believe to be true, most of what they think they know, is literally made up... products of the human mind, massaged or polished by social discourse and elevated to the status of received wisdom by custom or formal agreement. All cultural narratives, worldviews, religious doctrines, political ideologies, and academic paradigms are actually “social constructs” [domains of discourse].... One passively acquires the convictions, values, assumptions, and behavioral norms of his/her tribe or society simply by growing up in that particular milieu.... Some well-known constructs are entirely made up – “capitalism”, “communism”, “civil rights”, and “democracy” [aka human exceptionalism] for example, have no true analogues in the non-human world. These and similar concepts were birthed in words and given legs entirely through socio-political discourse [as honed into fine words by products of a broken educational system].... Science is unique among formal ways-of knowing in that scientists explicitly test the validity of tentative constructs (hypotheses) about the real world through observation and experiment [i.e. they listen to Nature] and adjust their understanding accordingly....'

'Things can get complicated – any economic paradigm is an elaborate socially-constructed model that may contain (or omit) other models that are themselves socially constructed. By now it should be clear that much of what humans take to be “real” may or may not bear any relationship to anything “out there”. More remarkably still, most people generally remain unconscious that their collective beliefs may be shared illusions – a cognitive enigma that may well determine the fate of humankind. No matter how well- or ill-founded, entrenched social constructs are perceptual filters through which people interpret new data and information; and, because our constructs constitute perceived reality, they determine how we “act out” in the real world. Millions [or billions] of lives may be jeopardized if those in positions of authority [fail to listen to Nature,] cherry-pick data guided by some dangerously faulty but comfortable social construct.... Let’s acknowledge that all economic theories/paradigms are elaborate conjectures and that none can contain more than a partial representation of biophysical, or even social, reality. If this is an important general limitation, we should be particularly concerned about today’s dominant neoliberal economic paradigm (the economics of capitalism)... enamoured with the idea of a self-regulating (free) market, would have the real economy adapt to fit their models.'

—William Rees, End game: The economy as eco-catastrophe and what needs to change 2019

There is one leverage point that is even higher than changing a paradigm. That is to keep oneself unattached in the arena of paradigms, to stay flexible, to realize that no paradigm [belief system, ideology] is 'true,' that everyone, including those that sweetly sing your own worldview, has a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe that is far beyond human comprehension. It is to 'get' at a gut-level the paradigm that there are paradigms [that are not 'true'], and to see that that itself is a paradigm, and to regard that whole realization as devastatingly funny. It is to let go into not-knowing, into what the Buddhists call enlightenment.

It is in this space of mastery over paradigms that humans throw off addictions [their purpose-driven Calhoun-rat consumer life], live in constant joy [when not dealing with life debilitating situations], bring down empires [so what are you waiting for?], get locked up, or burned at the stake or crucified or shot, and have impacts that last for millennia.

There is so much that could be said to qualify this list [see chapter six] of places to intervene in a system. It is a tentative list and its order is slithery. There are exceptions to every item that can move it up or down the order of leverage. Having had the list percolating in my subconscious for years has not transformed me into a Superwoman. The higher the leverage point, the more the system will resist changing it—that's why societies often rub out truly enlightened beings.

Magical leverage points are not easily accessible, even if we know where they are and which direction to push on them. There are no cheap tickets to mastery. You have to work hard at it, whether that means rigorously analyzing a system or rigorously casting off your own paradigms and throwing yourself into the humility of Not Knowing. In the end, it seems that mastery has less to do with pushing leverage points than it does with strategically, profoundly, madly, letting go and dancing with the system.