WEDNESDAY, SEPT 21, 2022: NOTE TO FILE

Transcending Our MTI Form of Civilization

A presentation by Ruben Nelson

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: MODERN TECHNO-INDUSTRIAL CULTURE, FROM THE WIRES, WE HAVE MET THE ENEMY

Abstract: Ruben Nelson is among the few (as in count on one hand few) whose life's work is not based on endeavoring to save life as we increasingly urbanized modern humans know it. If we have many problematiques (wicked problems) that are subproblematiques of our meta-problem (overshoot), perhaps tweaking our Modern Techno-Industrial (MTI) way of living, feeling, thinking, valuing, knowing and doing things... to solve whatever problems there may be (or may arise) that may pose an existential threat to our persistence (and destiny, e.g. to achieve true freedom and dignity for all or a Real Green New Deal, or...) is a fatal failure to understand that we are the problem we would seek to solve in all cluelessness. What if transcending our current form of complex society (the one that is not remotely sustainable and is laying waste to a planetary life-support system), was the most important work anyone could wake up each morning to in the 21st century? Could you spread the word and the work on social media? Three months after being uploaded to YouTube, 460 views and 17 Likes (I like but I don't do Likes, so I didn't click the button) and counting.

"If you insist on knowing things..., that no one else in your community or your culture knows, the human response everywhere, always, is to shun you to the point of death, or kill you." —Ruben Nelson.

[If you would rather know than believe (in the superorganism's consensus narrative), then you will be shunned (or worse) in modern techno-industrialized society (form 3), or in settled agrarian societies (form 2), or in indigenous societies (form 1), i.e. in any 1-3 form of civilization. Creating a viable form 4 civilization involves being shunned by ones community of origin, including ones family. The "rather know" option, which excludes belief in belief, is not possible for normal clothed apes—the cost is too high, and so "people would rather believe than know" —E.O. Wilson.]

COOS BAY (A-P) — Ruben Nelson's presentation to the Canadian Club of Rome members and such as may have learned about it before June 22, 2022 (thirty some attending a Zoom meeting), may be too few to start a revolution. Revolutionary change (e.g. transcending our MTI form of civilization) always comes from the few to whom it initially seems they may be the only one (and one always is), but eventually (if they are not the only one, e.g. Ted Kaczynski) they may learn of others having similar concerns and recognition (understanding) of the need for foundational change (as distinct from ideologues who believe that change would be like so needed, the best thing ever by telling potential followers what they want to hear, a fault Ruben seems incapable of). Understanding, based on a lifetime of inquiry and endeavor to envision and foresee, gives raise to a choiceless awareness of conditions past, present, and probable future that compel existential concerns, a need to understand the rules of the game and endeavor to play it well enough to persist (not as an individual subsystem of a species/biosphere, but as embodied in posterity as they who may live properly with the planetary life-support system and thereby persist as evolvable subsystems).

Given that political revolutionaries are part of the problem, the question of whether there are enough apolitical revolutionaries out there to transition to a new Civ 4 complex society that is not too overcomplex to persist, remains to be seen (likely this century as the coming years of our overshoot and degrowth condition 'must show' as Charles Dickens might say, or 'dissipates' as a complex, adaptive, dissipative structure that is foundationally other than a complex, adaptive, evolvable system in the systems science thermodynamic language game). Apolitical revolutionaries include H.G. Wells whose vision of things to come was 'a theory of world revolution.', John B. Calhoun as a compassionate revolutionary seeking prescriptions (Rx) for our continued evolution, and M. King Hubbert's technocracy alternative to what was looking like a failing hegemon in the 1930s, but recovered (drill baby drilled) for a time (until our time). H.T. Odum's 'system over self' has profoundly revolutionary implications. William R. Catton, Jr. called for revolutionary change in 1980, and Paul Ehrlich's call for a 'survival revolution' in 2021 is a call for all good humans who can see what is in front of their pug-nosed faces to do something. Donella Meadows spoke of the one leverage point that leads to mastery over all paradigms, the basis for a memetic mutation that could enable revolutionary change at the civilizational level. Barbara Williams and Jack Alpert may not see themselves as revolutionaries (they still believe in political solutions), but the change they envision would be revolutionary if it could be. And Ruben may not be taking up arms against a sea of troubles, but those who would should hear him out, give him 'a careful hearing'.

Byway of doing the careful hearing bit, listen to his presentation, then read and reread between the pauses his words and graphics to see beyond, to look upon the nature of things and to listen to Nature who has all the answers.

Transcript:

Hello, I'm Ted Manning, I'm your host today and I have a very colorful and interesting and forward-looking person with us, Ruben Nelson. Some of you who may not have met him. I was lucky enough to meet him way back last century when we were both stuck in Environment Canada and he has been talking about the future for longer than almost anyone else in Canada and sometimes to pretty good effect. It's always been a challenge to get the bureaucrats the politicians and others to believe that the future has anything to do with their very short time frames and the other deliverables, and Ruben has taken that challenge up and he has had influence on the decision process on social policy, on environmental policy, on really getting people to be comfortable about talking about the future and its implications for what it, what they're doing. So I'm delighted to, I'm not going to tell you a lot of stuff about Ruben, there's an awful lot of stuff there, of the impacts of what he's done on policy in Canada and Alberta and overseas, but he will be drawing on that to tell you his current fixation, which is to try and get people out of a particular mindset on modern techno-industrial cultures that really do not seem to allow solutions to the kinds of problems that we've all been identifying. So, Ruben, delighted to have you on board and I will turn it over to you.

Thank you Ted, and thank you to all who are on this call. I look forward to engaging with you later, and I also want to thank all who watch it, without an opportunity to engage, watch it on YouTube, so I put the URL for CACOR there and hope that many of you will connect with CACOR and become involved. I want to think with you about transcending our MTI forum civilization, and I hope by the time I'm finished, you'll understand what I mean and intend by that phrase.

I use modern techno-industrial as a technical term to denote the form of civilization that began to develop, the roots of it a thousand years ago, in northwestern Europe, and it's the forum civilization that is now essentially the owner of the planet And I'm worried that it thinks it's the future, and I've become convinced through my work that it's not. And more of us believe the culture we've been shaped by than believe me, and there may be good reasons for that, but there we are.

So Albert Einstein said that you have to learn the rules of the game, and then you have to play better than anyone else.

So what game are we in? If we don't understand the game we're in, we're not likely to play well.

And it turns out that it's the Earth's game, and some insights into the Earth's game.

Reality is construable, and the cultures we co-create construe it.

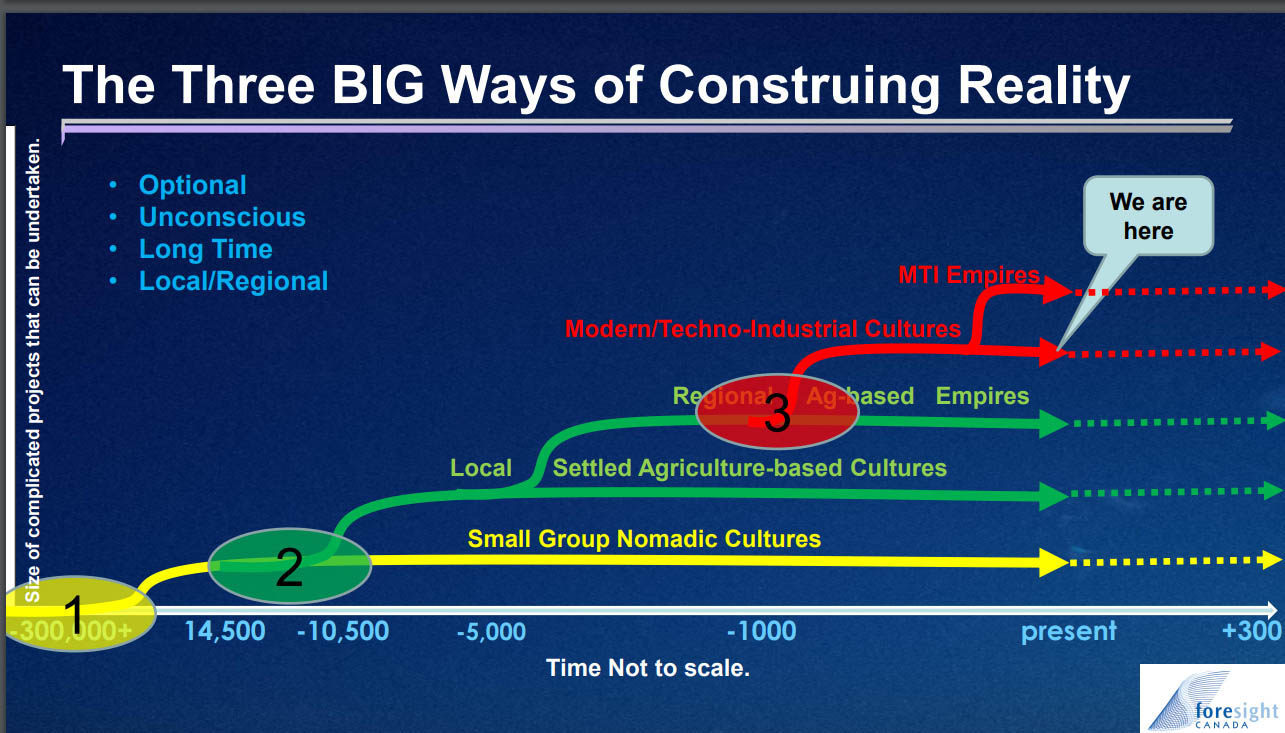

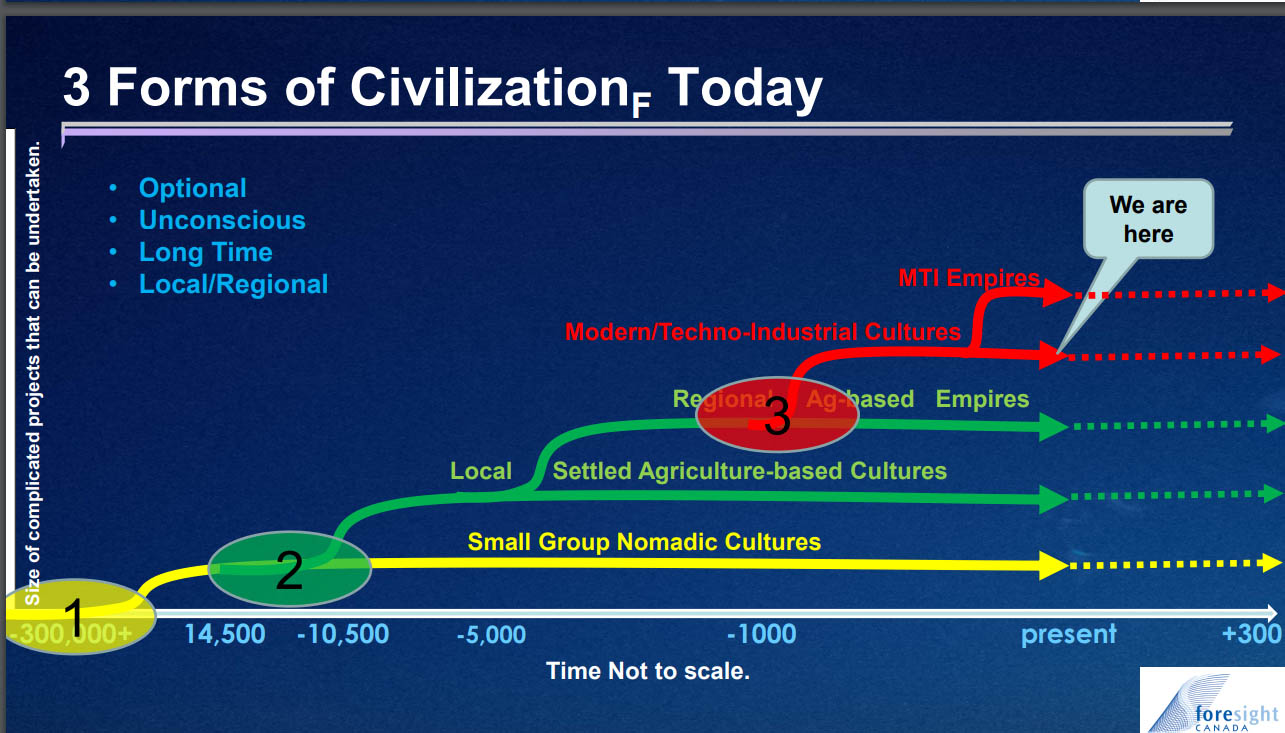

The way we apprehend reality determines our responses to it, and I want to suggest there's only three big ways of construing reality that have developed so far in human history.

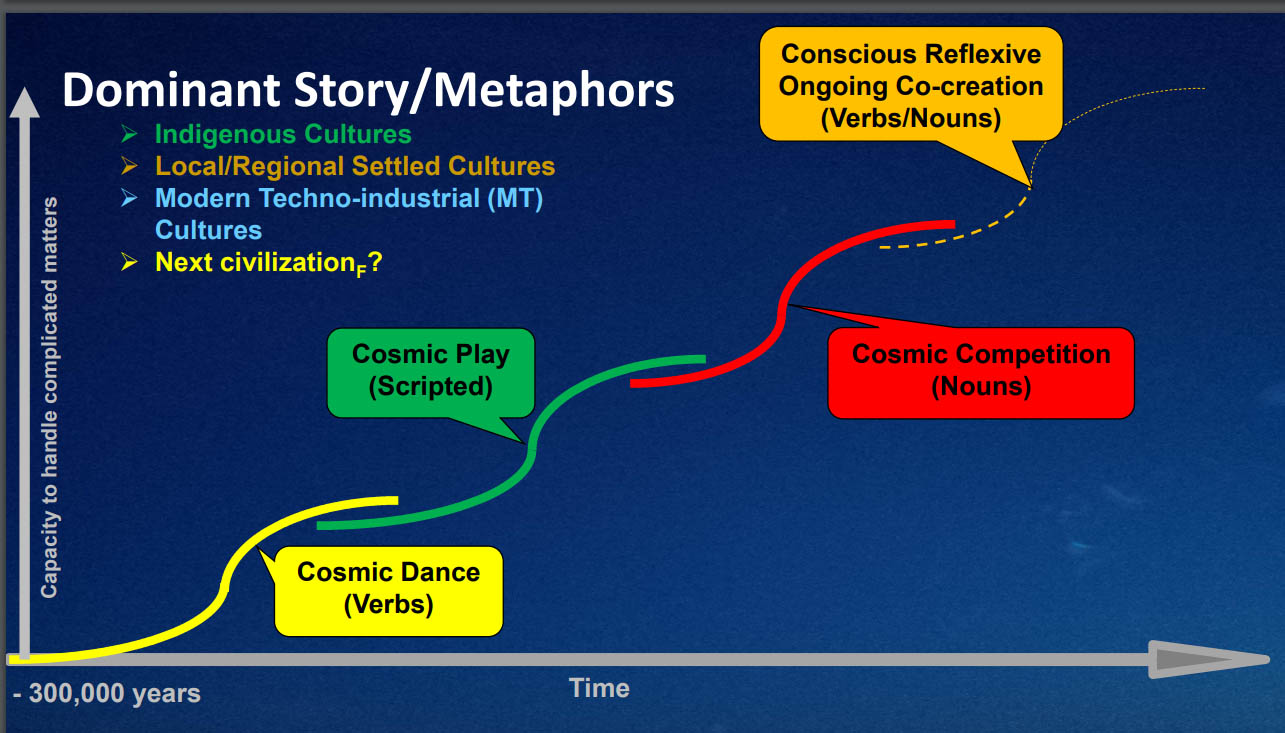

Doesn't mean there may not be others, but if you look over the last three hundred thousand years, you find that the first way was we developed cultures that were small group nomadic cultures, and up until about 12,000 years ago, they were the only form of civilization on the planet.

Every culture was an exemplar of small group nomadic cultures, and then, with Holocene agriculture became possible. It was optional, wasn't required, and so eventually local settled agriculture-based cultures emerged. And then in the last thousand years we have developed our modern techno-industrial cultures. And that we are here is, for Canadians, because nobody talks about a Canadian Empire, the last two forms of civilization, empires can emerge.

All cultures assume their own rightness and continuity. None are open to dramatic discontinuity. All are path-dependent, and only MTI cultures expect ongoing "improvements" in progress.

The earth sets the conditions, offers clues about the game, there are no clear instructions, and it's the referee as to when you get thrown out of the game. And it appears that you must not destroy the earth's living ecology to the point it can no longer support us; that we must not consume non-renewable resources to the point where diminishing returns become lethal and we must honor these first two conditions and be humane enough with each other to keep the game going.

You fail any one of those, let alone all of them, and you're out of the game.

So what game are we playing?

Well, we're playing the MTI Game and we believe that any decent future for humanity entails the extension and improvement of our MTI form of civilization MTI can be taken to and beyond the ends of the earth and extended and improved forever. Doing so is the primary responsibility we have as MTI persons, communities, jurisdictions, and cultures.

Yes, we face horrendous problems, but problems have solutions and a better version of MTI will do the trick. We all know what needs to be done and have the capacity to do it. So all we lack is the political will, leadership, and funding to inspire our innovation, creativity, and entrepreneurship. I'm not suggesting that every last person in an MTI culture believes that, but it is the overwhelming message of virtually every university on this planet.

If you think about that, that's worrying. Governments, many churches even, every chamber of commerce, every business leader.

Margaret Thatcher said there is no alternative to it,

so that the MTI cultures are hooked on the thought that any problematic condition can be understood and dealt with from within the MTI frame of reference, and that raises the question of what is that frame, and by the time we're finished, I will have explained that as I understand it.

But the point I'm trying to make right now is that we're civilization trapped. That we who are MTI are so far into our belief system about the efficacy of modern techno-industrial cultures, that we give no thought to the possibility that a profound source of our trouble may be the very way we, as MTI persons and cultures, understand, approach, apprehend and respond to reality.

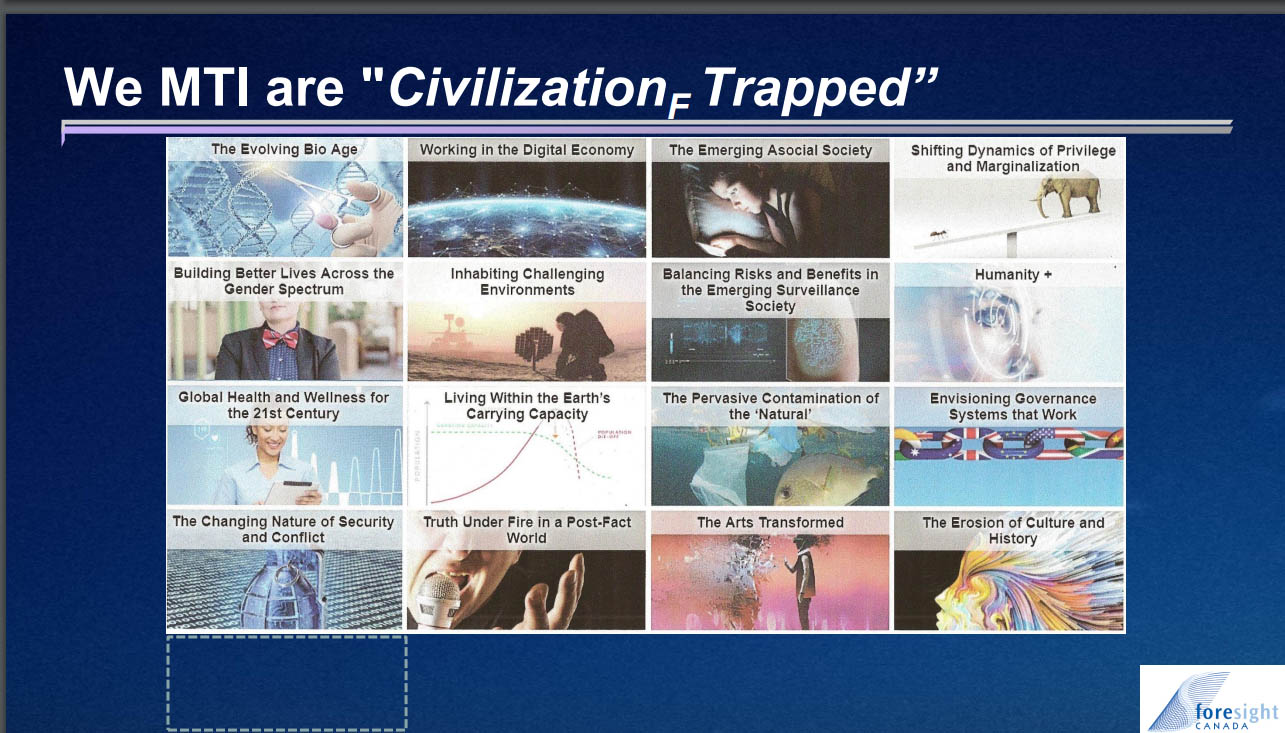

So, here you see the 16 big issues that were identified for SHIRK and those of you who don't know SHIRK, it's the funding body in Canada that funds the social sciences and humanities in Canadian universities, and SHIRK approached Horizons Canada a few years ago and said we, in our futures program, we want you to give us a fresh statement of the grand challenges for humanity and Canada in the 21st century, at least out to 2050, and preferably beyond.

And their report is on the Horizons Canada website and these are the 16 spaces that Horizons Canada offered, and said either in that space alone or by mixing and matching them, we think you can. We've covered the ground and if we said to Horizons Canada, well, we think you've missed something. Being nice and humble people they would draw a little dotted line, as I have down in the bottom left-hand corner, and say, well tell us, what we've missed we're happy to include it. And I would say no, no, no, you haven't missed something that's the direct analog of what you've got. What you've missed is the very thought that this way of construing a reality, this way of cutting it up, of organizing it, of thinking about grand challenges, is a very modern techno-industrial way of doing it, and you have done it in a typical way that is unreflexive.

So the thought, that the need to transcend MTI cultures and mature into the next form of civilization, is not on your list and what's more, it's not on the list of any grand challenge of any institution in the world.

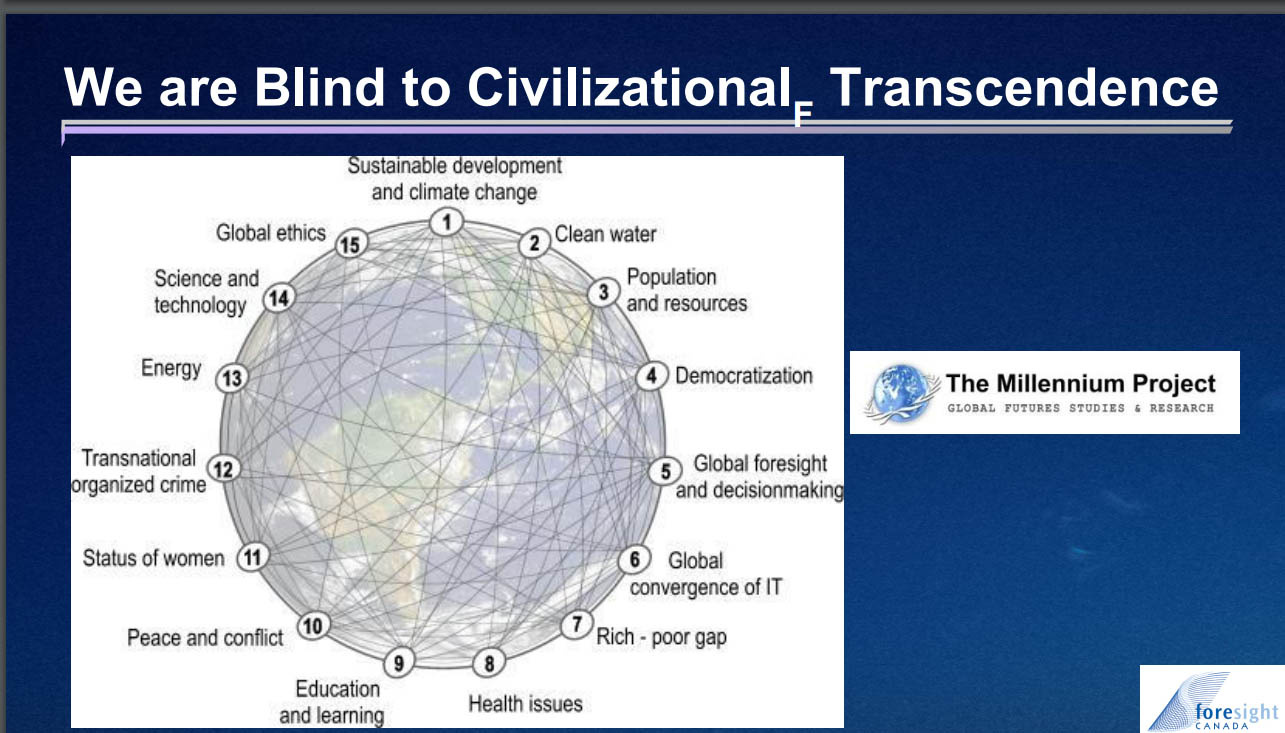

This is just two examples: This is the Millennium Project. For 25 years or so this has been their 15 major problems. There's not a hint in any of that that our MTI consciousness and cultures are an issue to wrestle with.

Cambridge was the Second Institution for Existential Risk, Oxford was the first, they're growing kind of like mushrooms in the spring because in certain universities it's fashionable to have one of these things, and Cambridge says we're dedicated to studying, mitigation of. the risks that could lead to human extinction or civilizational collapse. They do not have MTI cultures on their list, nor do any of the others.

My point is that MTI cultures, because of their very nature, are context blind, and if you are context blind then you don't do the future very well because the future is entirely a space where context is king.

The heart of futures work is understanding the subtle ways in which our context is changing, not just at the surface, but deep within us and as Louise Penny, the Canadian author, wrote in 2018, 'nothing good ever came out of a blind spot'.

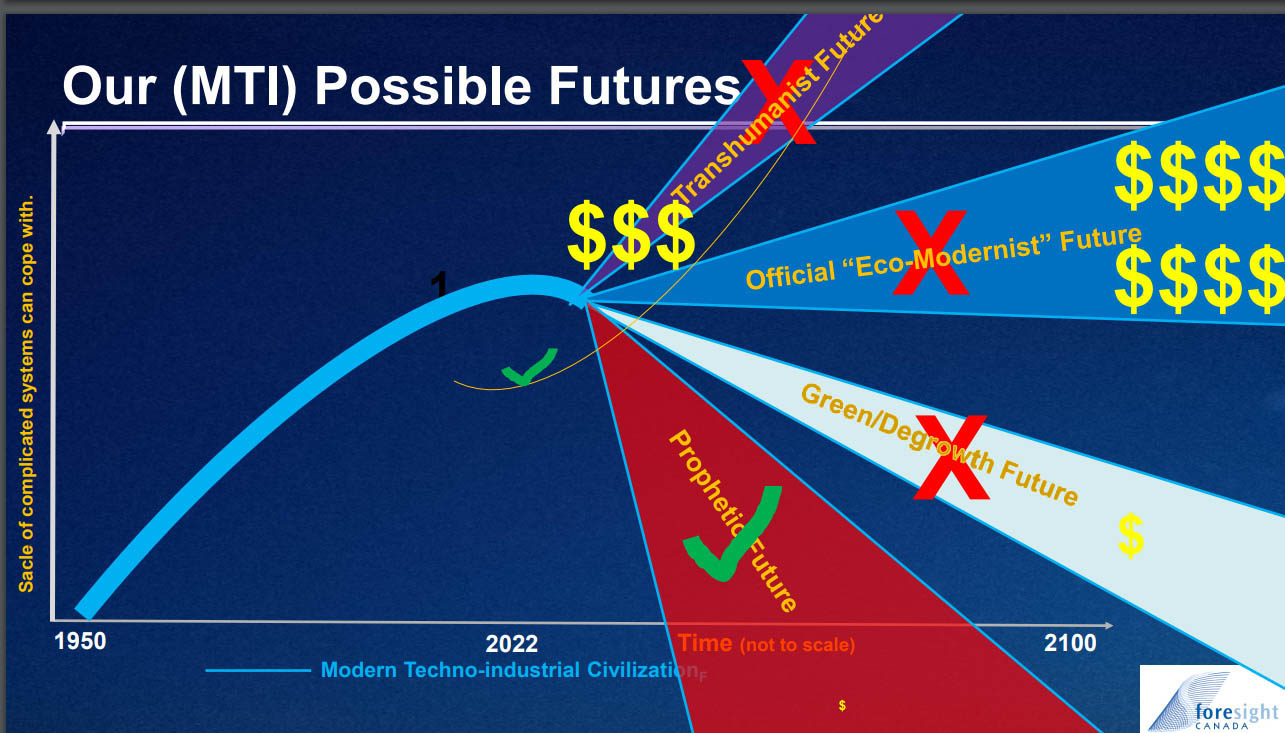

So, I'm suggesting that there are only five possible futures, lots of variations of them, and the dollar signs indicate where we're actually putting our bets and our money as a culture and so most of it of course is to continue our MTI cultures in some kind of eco-modernist way. And all that means is that we believe in ourselves, we believe what we've done, we think that science and technology is the clue to everything, with, you add a couple of economists on the side, and give it lots and lots and lots of money. So it's STEM times M is the formula, and the fork that M is money.

That, in fact, is what's happening around the world. The second most significant amount of money is being spent by extraordinarily rich men, who are not much more mature than adolescent males, which is normal for modernity, and they want a transhumanist or post-humanist future, and they're busy playing with that. So far as having no significant impact it may come to. There's another group of people who understand that modernity is past its peak, and in decline, and are arguing that if we manage that decline, we'll be better off than if it just happens to us, and some of them are people arguing for green growth, others are under the heading of degrowth. They don't have much money. These are good and earnest people, not much money, and a voice that is being heard some, but largely ignored by official bodies.

And then there are a few prophetic voices. Now prophetic voices are not simply, 'the end is near'. That kind of an image doesn't understand biblical prophecy, and it's likely the case that most of the cartoonists who wrote that stuff don't read the Bible, which is perfectly normal today. But old testament prophets were people who had a deep passion for the future and authenticity of Israel. What they were saying is, Israel you are now living in a way that leads to death, that the fruits of your labors will be death for you, and your children and your grandchildren, but so therefore become conscious of that, become reflexive and change, and move on to a new path, and there are people singing that song, as we'll see.

And then as you'll see, that little orange line that also has a check mark beside, there are people who say the path we should move on to is not improving modernity, but is actually the next form of civilization, and that voice is so weak, that in the chorus of noise, it's hardly heard at all.

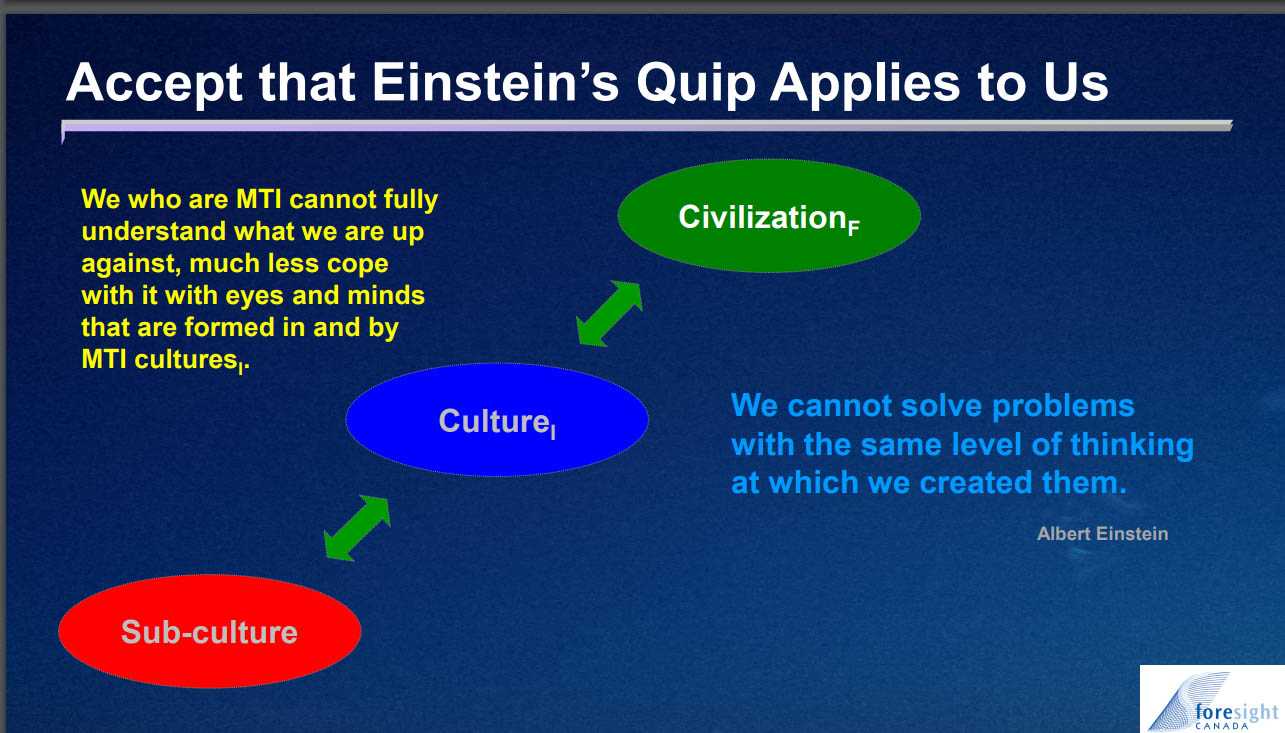

So the first big step that we have to do is accept that Einstein's quip applies to us as modern people.

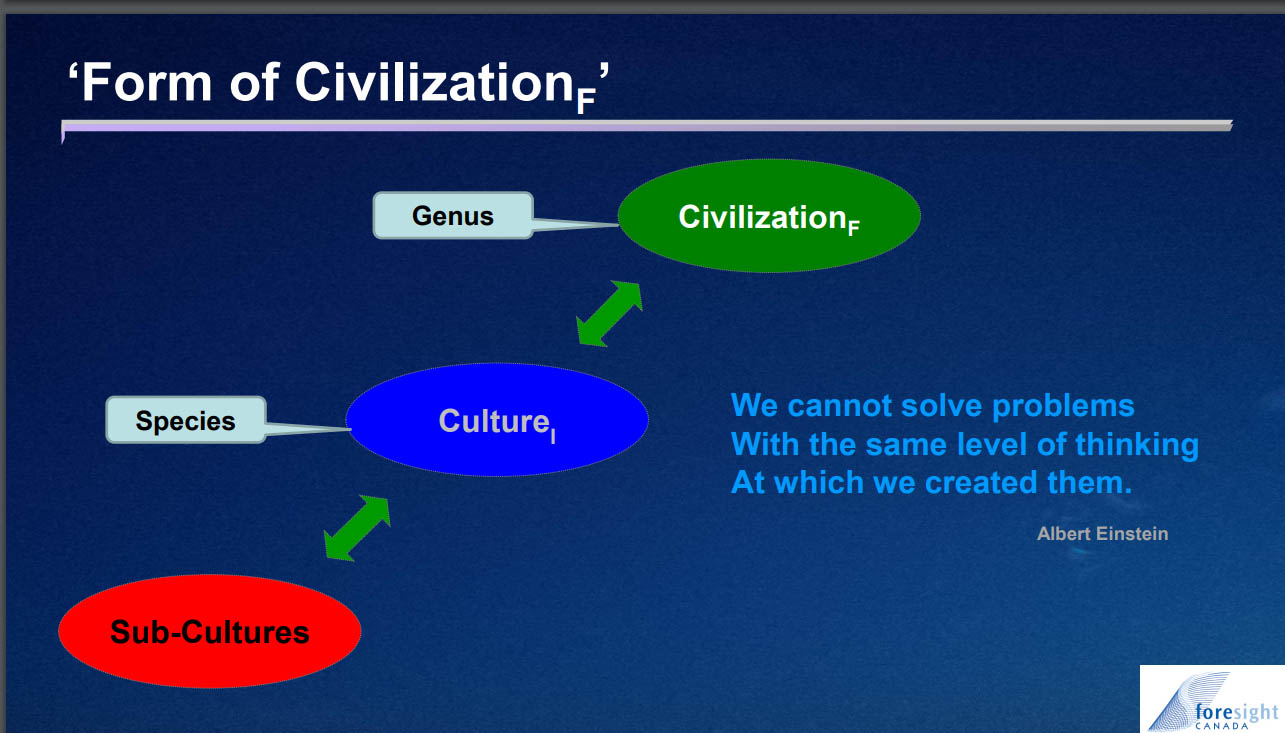

His quip was, we can't solve problems at the same level of thinking that created them, and I'm suggesting that we who are modern have to take that seriously and understand it. That we who are MTI cannot even fully understand what we're up against, much less cope with it, as long as we're working with the eyes and minds and habits that are formed in and by MTI cultures. So that the implication of a new level of thinking is actually a new form of civilization.

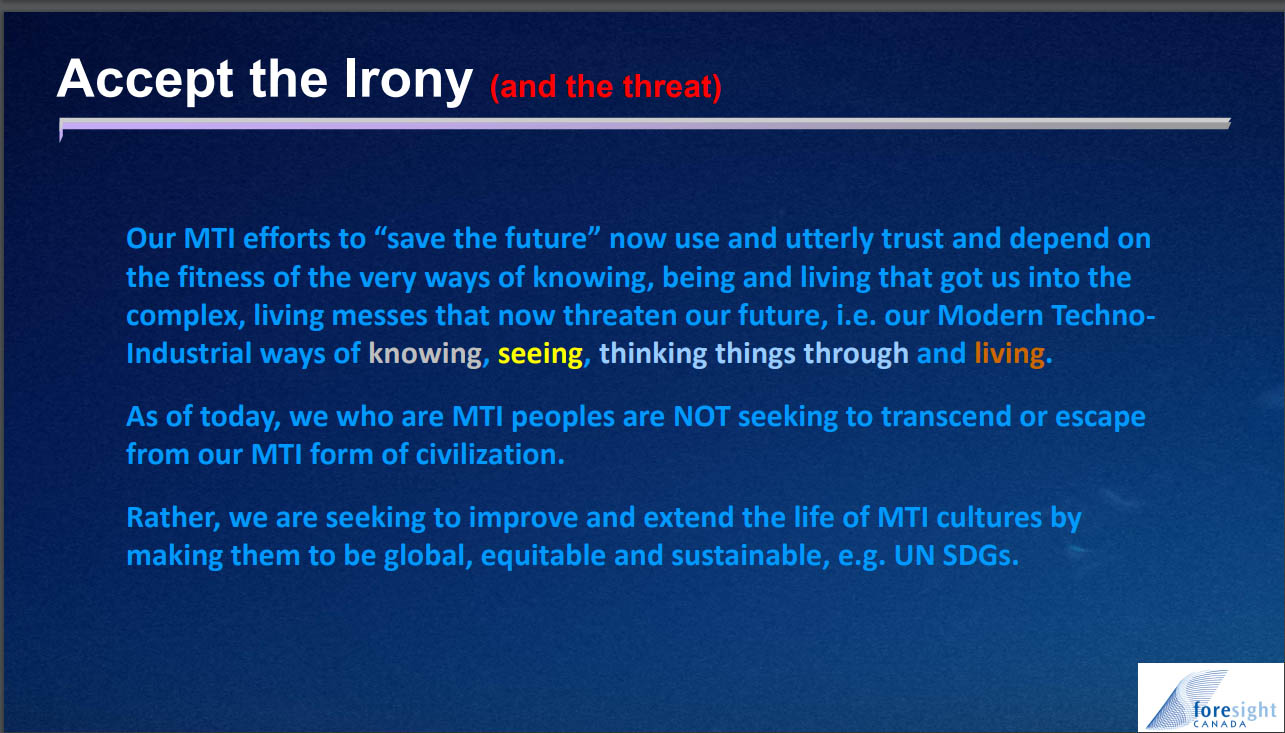

And we have to accept the irony there's a threat in it as well, that virtually all the MTI efforts to save the future, and you know that that's now a multi-billion dollar global industry, now use and utterly trust, and depend on the fitness of the very ways of knowing, being and living that got us into the complex living messes that now threaten our future.

Our modern techno-industrial ways of knowing, seeing, thinking things through, and living (and I'll just remind you that you'll see that phrase and that color coding again and again, I will explain it later) as of today we who are MTI peoples are not seeking to transcend or escape from our MTI form of civilization. Rather we seek to improve and extend the life of MTI cultures by making them to be global, equitable, and sustainable... and one example is the UN's Sustainable Development Goals, and I know it sounds heartless to say, but surely you can't mean that helping other people have a life that's at all akin to a decent life is evil, and I'm not suggesting it's evil. I'm just suggesting it's wrong-headed because it's still within the illusion that this earth can sustain eight billion people, or whatever your favorite number is, as modern techno-industrial people.

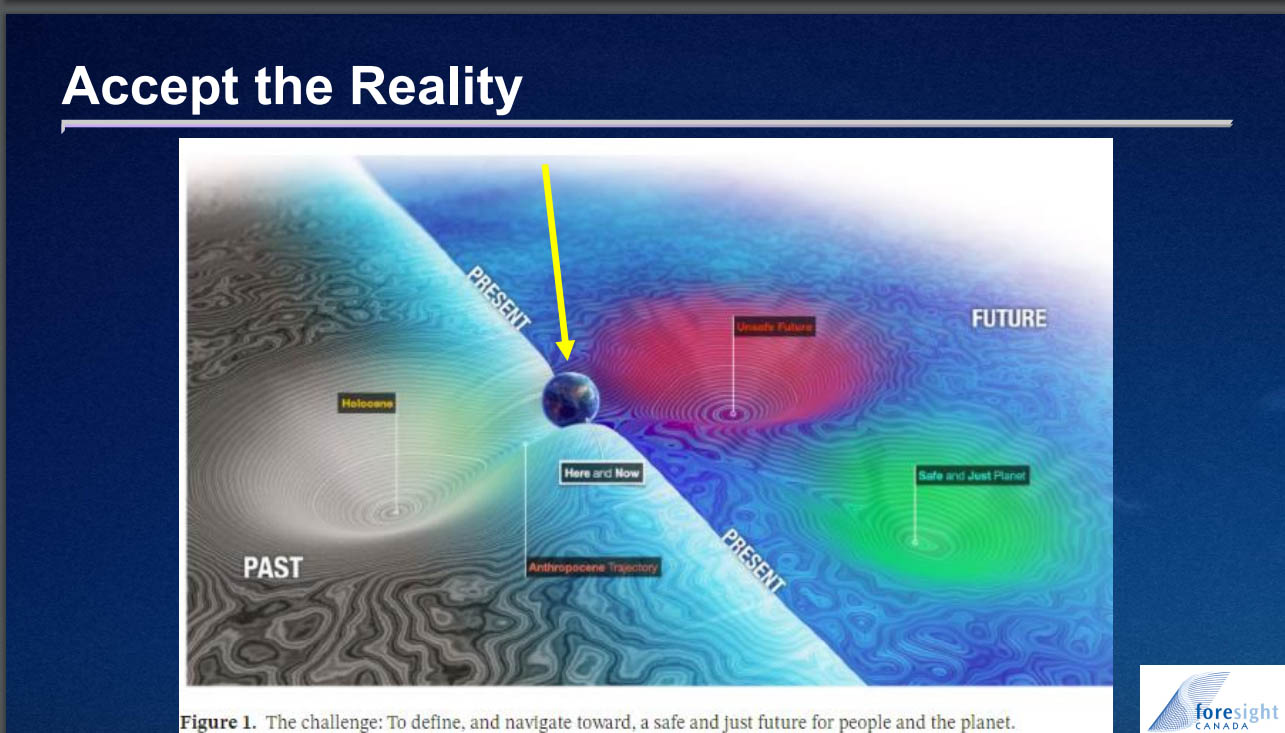

This image comes from our friends who do complexity theory and it's simply reminding us that our modern techno-industrial way of life is spinning the earth out of the basin of attraction which has been the Holocene. It's the basin we've been in for 11,000 years with a climate that's very conducive to us, and millions of other species. Now, the modern and techno-industrial world believes we're still in the Holocene and will be there forever. Well, in other words, they think this is fake news.

Unfortunately, it's not. The whole talk of the Anthropocene is to say that we now affect the earth and its future to the point that we are spinning out of the Holocene into a new basin of attraction, and there's really only two to choose from. One we can live in and one that we can't, and people who pay attention to these things are pretty much agreed that the odds, that the chances, that we'll end up in the red basin are very high.

The odds that our grandchildren and their grandchildren will be in the green bases are very thin indeed.

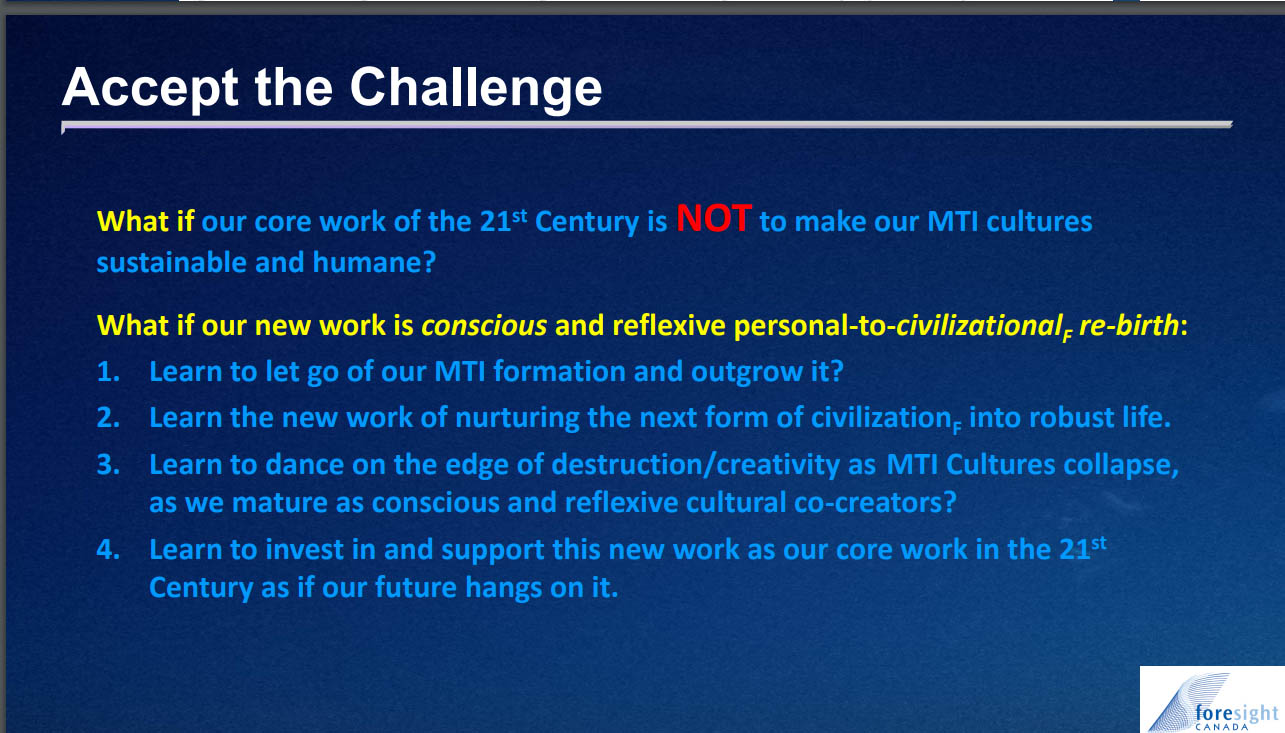

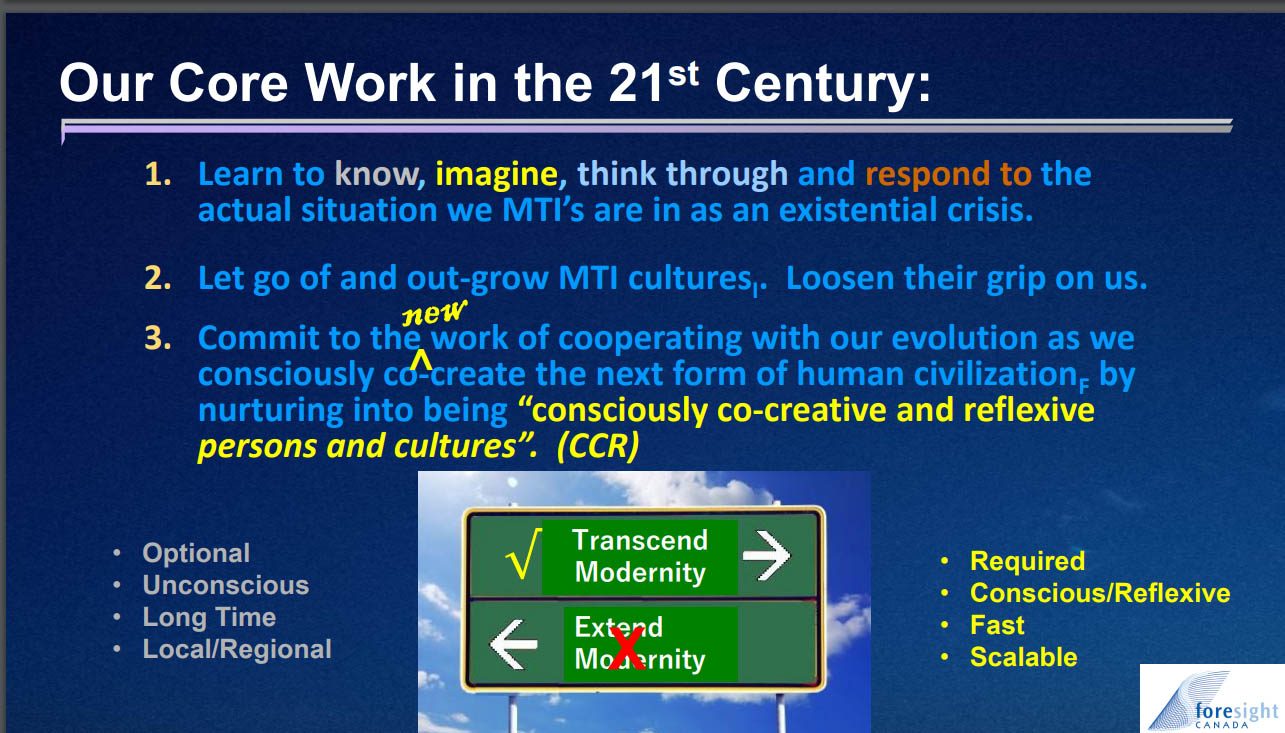

So we need to accept this challenge. And in saying what, if I honor Rob Hoffman, whose firm was What If Technologies, a long time member and a great friend and colleague in CACOR, but what if our core work in the 21st century is not to make MTI culture sustainable and humane?

What if the UN and most of the modern world is simply wrong about this? What if our new work is conscious and reflexive personal to civilizational rebirth? Learn to let go of our MTI formation and literally outgrow it, learn the new work of nurturing the next form of civilization into robust life, learn to dance at the edge of destruction and creativity as MTI cultures collapse. And as we mature as conscious and reflexive cultural co-creatives, learn to invest in and support this new work as the core work of the 21st century as if our future hangs on.

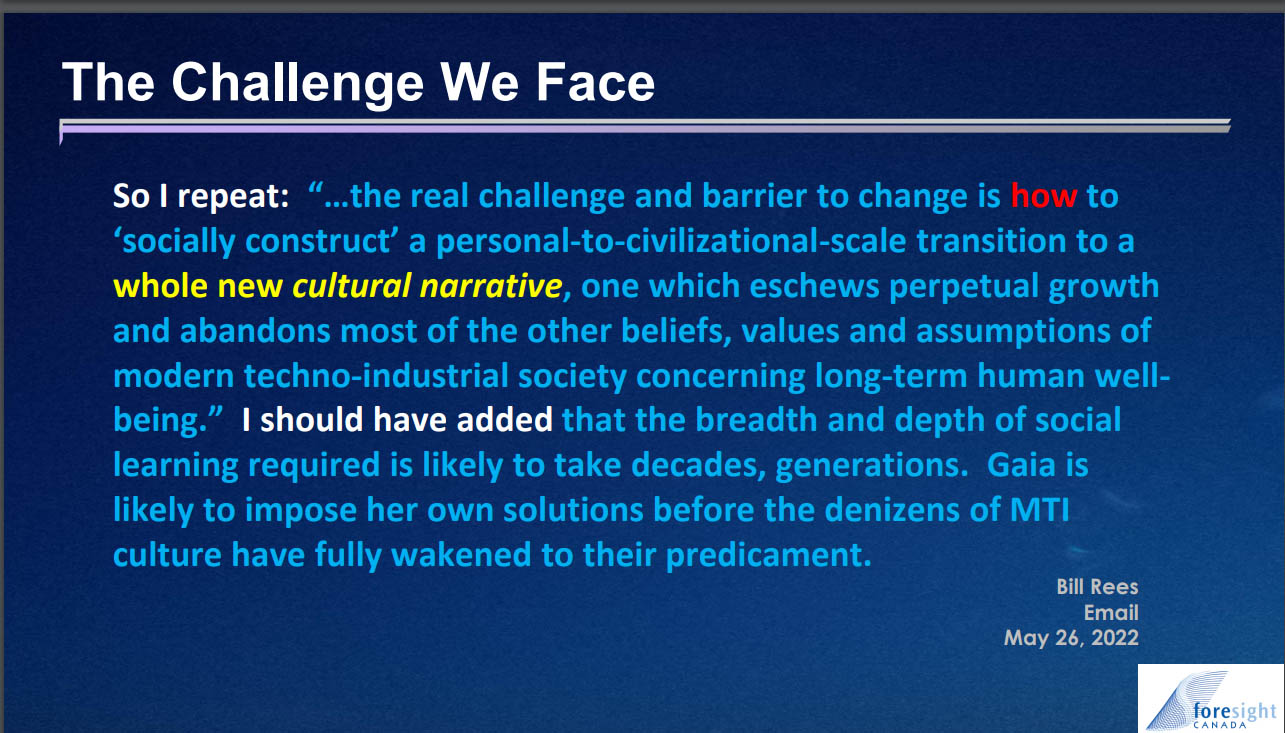

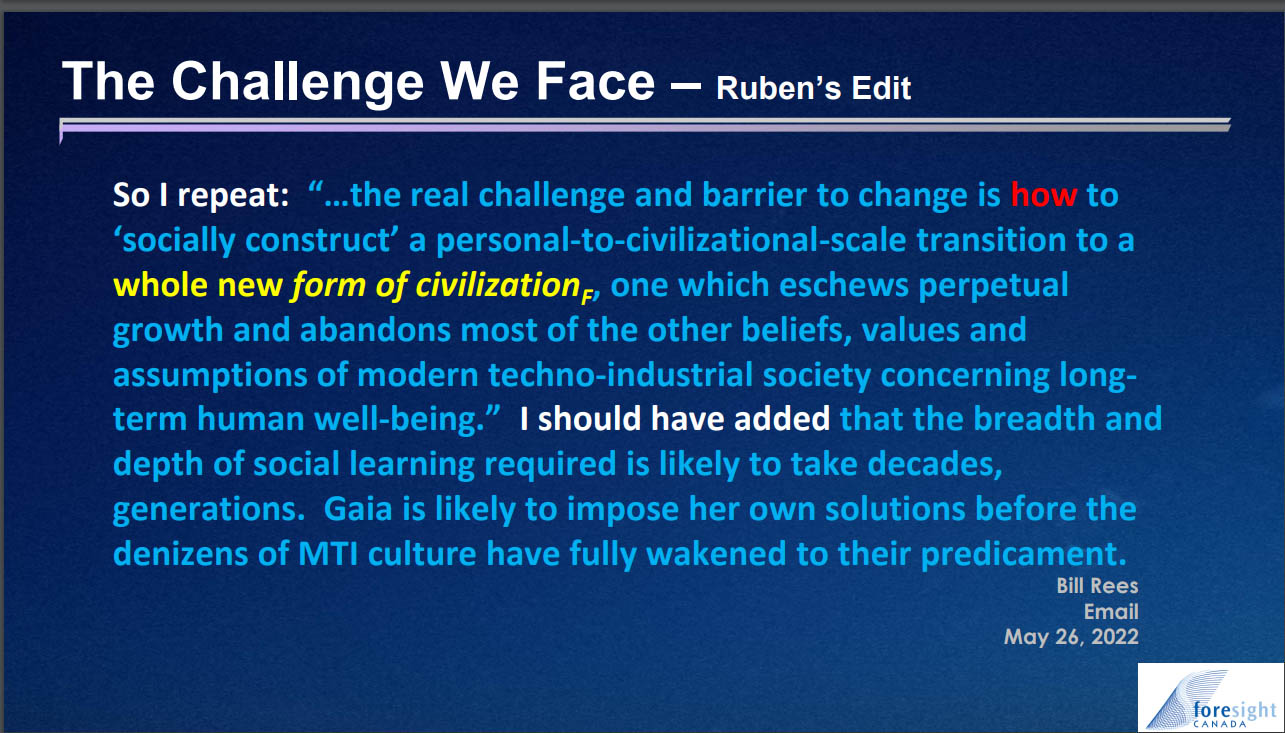

And here we come to Bill Rees. I promised we would get to him, eventually. Bill, this is from an email that was part of a listserv I'm on less than a month ago, in which he said, so I repeat, the real challenge and barrier to change is how to socially construct a personal to civilizational scale transition to a whole new cultural narrative, one which excuse perpetual growth and abandons most of the other beliefs, values, and assumptions of modern techno-industrial society concerning the long-term human well-being. I should have added that the breadth and depth of social learning required is likely to take decades, generations.

Gaia is likely to impose her own solutions before the denizens of MTI culture have fully awakened to this predicament. And I want to say that there's nothing that Bill says there I disagree with. I think he may be the wise, the wisest ecological economist on the planet today. The only thing I would change is his phrase 'cultural narrative' and I would change it to 'form of civilization'.

A form of civilization includes a cultural narrative, but we need more than a cultural narrative. We need a form of civilization.

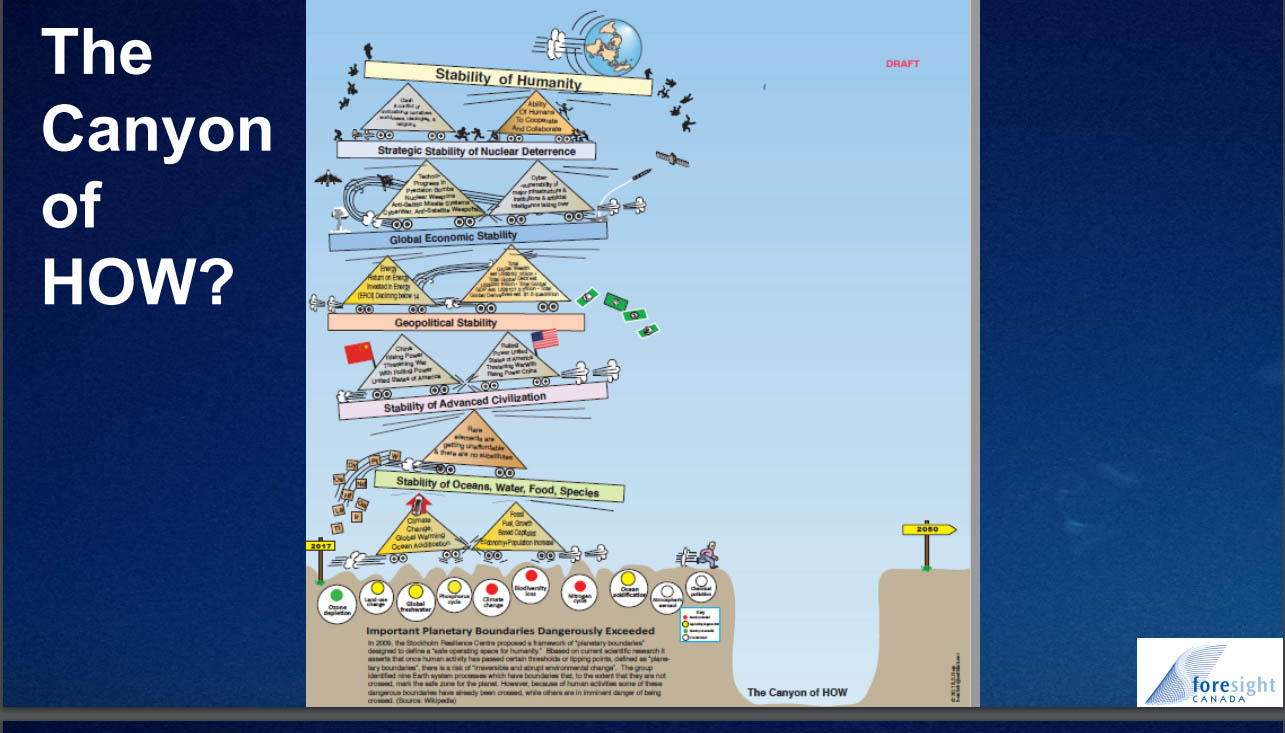

I've used that phrase before, I'll use it again eventually. I will explain it, so here is the Canyon of How.

This is the question that Bill raises. How do you do this? How do you get people who are still basking in their extraordinary success, and try to have them hear the fact that that extraordinary success is self-limiting and therefore we're not long for this world, and that we need to engage in a transformation that is far more profound than anything that any serious institution is even talking about.

And Bob Horn, my colleague, drew this image of all the different bits of our modern world and how precarious each of them are, and they're all on roller skates, and how do we get over into the future?

So what to do? Well as one trained in philosophy, political theory, and theology, one of my instincts, just given my training, is to clarify the terms,

and I recognize that the conversation about fundamental change is gathering strength.

I'm thankful for that, but in my view it is inadequately conceived and theorized at this point of its development, and this includes the multi-billion dollar sustainability industry, the folks who talk about a great transition, the great work, on and on, and on. System change, not climate change, a life-affirming culture,

and on we go, and so I want to offer two definitions just at least you'll be clear about how I use the language.

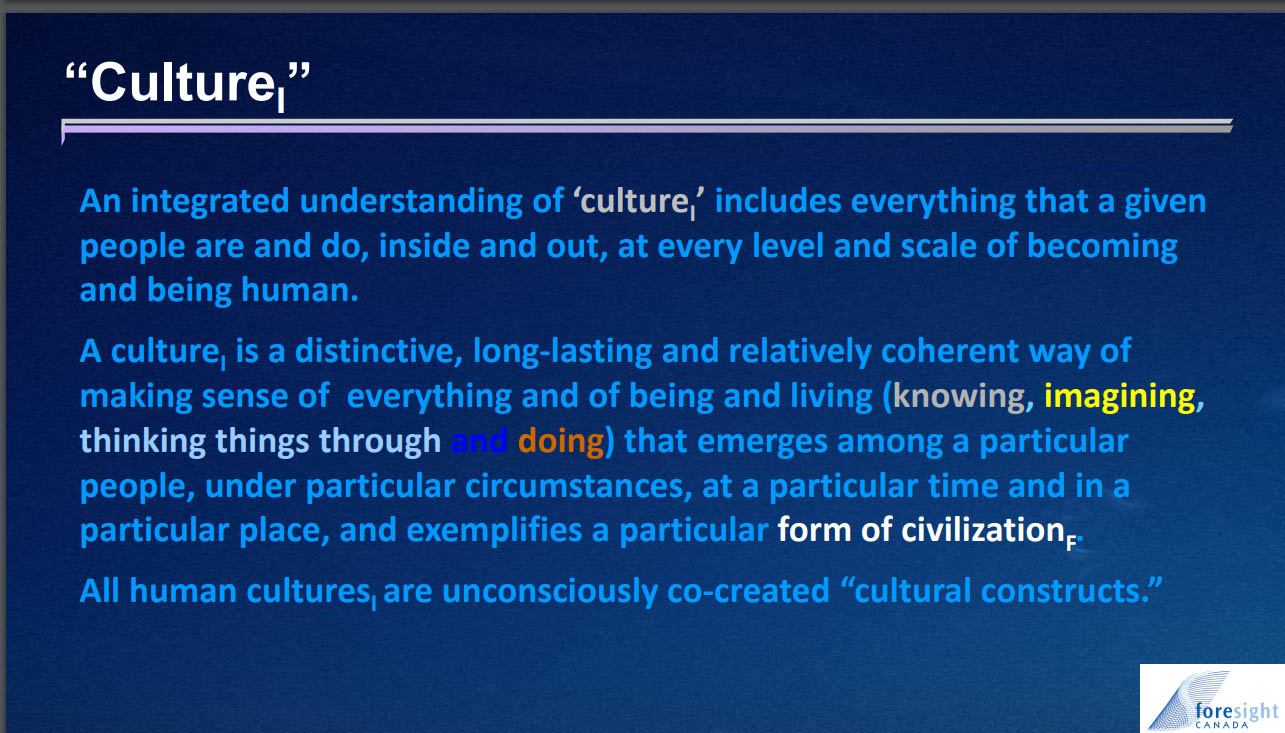

You don't have to agree with me, but I want to define an entity that is... I use 'culture' subscript 'I' because that's an integral use of the word culture. When you have an integral understanding of anything it means that all the things that it are, nothing is left out. There's no externalities. Everything is included and so I want an understanding of culture that is integral in that sense or includes everything that a given people are and do both inside and out at every level and scale of becoming and being human.

That a culture, in this sense, is the distinctive long-lasting, relatively coherent way of making sense of everything, and of being and living, knowing, imagining, thinking things through, and doing that emerges among a particular people under particular circumstances at a particular time, in a particular place, and exemplifies a particular form of civilization.

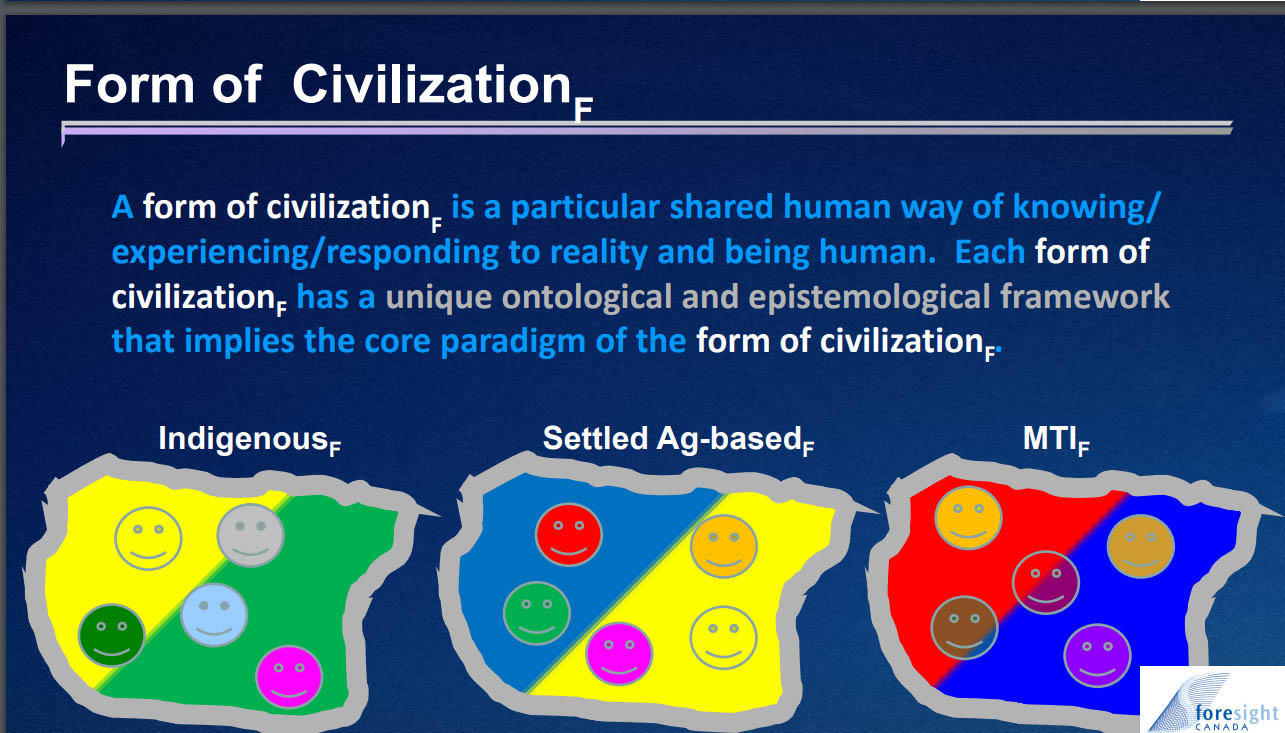

All human cultures are unconsciously co-created cultural constructs, so that's what I mean if I'm talking about a culture that exemplifies a form of civilization. So here at last is an understanding of 'form of civilization'. It's at a higher level of generality than a culture, in the same way that fruit is at a higher level of generality than apple, or vegetable is a higher level of generality than potato.

So a potato is a species of the genus vegetable. An apple is a species of the genus fruit, and Canada is a culture of the genus modern techno-industrial. In, and acknowledging that, we also have here a significant presence of indigenous people who live by a different form of civilization.

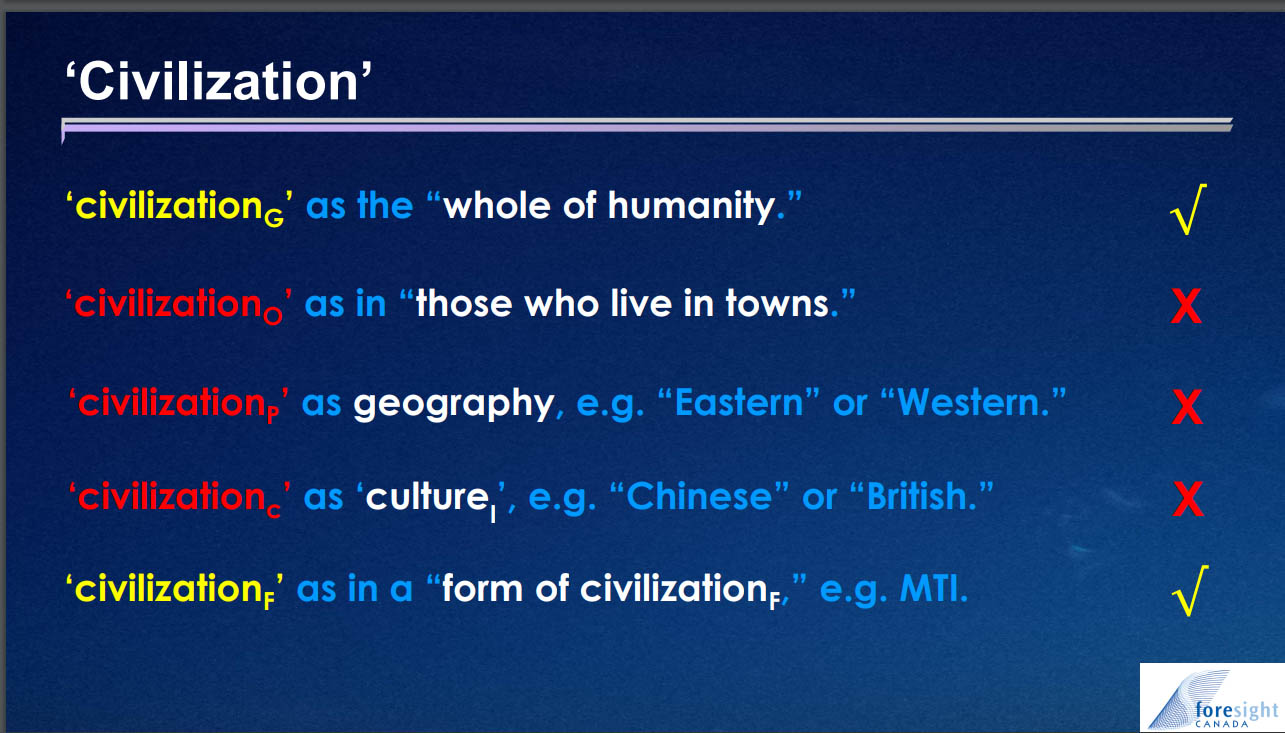

So I'm using civilization in a way that is not yet common, it's not yet an idea in good currency. I coined this phrase in 2018 for a talk I gave in San Francisco, so there are other uses of the word civilization.

I just very want to quickly either affirm them or get them out of the way. The one I affirm is civilization subscript 'g' for global as in the sentence 'human civilization is at risk', meaning the whole of humanity is at risk. Perfectly useful way to use the word 'civilization'.

It's not what I mean by 'form of civilization', but it's a useful way. There are three other common ways it's used, and I suggest we simply abandon them. If you find yourself using them, wash your mouth out with soap. That's distasteful enough that eventually you'll stop. So civilization subscript 'o' is the original sense of civilization.

Civitas is one of the Latin words for city, and it was an early modern invention to say we who live in cities are more civilized, so literally for much of, if you look at the history done in the 19th century civilization, history is broken up in human history into pre-civilization and post civilization. In all, indigenous people who don't live in towns are not civilized. They are pre-civilized, and there ends up being a moral judgment in that from which the Stoney-Nakoda and other indigenous people suffer to this day. This is just a fantasy of early male industrial ignorance to not write history in a way that includes all of us as Homo sapiens is unconscionable in 2022.

Civilization 'p' is as geography western and eastern civilization. Again it's an early modern way that, as we began to travel, we found people on different places on the planet were quite different, but if you think about it, the the literal meaning is that there's something about longitude and latitude of this planet. If you live in one place, you have a culture of a particular form, and another place of a different form, and that's reports just a silly notion, so dump the concept.

And civilization 'c' is equally unjustified. That's using it as what I mean by the word culture in an integrated sense because civilization 'c' is simply kind of an honorific that inflates my sense of culture to say that these are especially important cultures.

So we talk in a low tone of voice about ancient Greek civilization, or the ancient Mayan civilization, and to this day Chinese diplomats go around the world speaking to their diplomatic counterparts in other countries, trying to intimidate the rest of us, by reminding us that in their view China is not just a country but a civilization. And we're supposed to hear that as something bigger and braver and more threatening than just a culture.

Horse hockey. It's not a useful concept you can cover everything that is intended cognitively by that sense of civilization, in my sense of culture. And civilization 'f', is simply civilization as a form of civilization.

So a form of civilization is a particular shared way of knowing experiencing and responding to reality and being human. Each form of civilization, and here's an image of three of them, they have unique ontological and epistemological frameworks that implies a core paradigm of the form of civilization. So now we're getting down to what defines a form of civilization, and how can we tell one from another.

And so the big thick green line that is around each of these three images is the ontological and epistemological framework of each form, and each form of civilization has a different, a somewhat different, ontological and epistemological framework and a different core paradigm.

So this means that we should listen to what indigenous people have been trying to tell us for several hundred years and that is, 'hey whitey, we who are indigenous have as many different culture forums as you, who are modern. You distinguish between Italy, Finland and Canada, and yet you can't distinguish between the Cree and the Stoney-Nakoda. You think we're all the same. We're just indigenous'. We're not, so by using the concept of a form of civilization.

We can say there's an indigenous form of civilization which allows many different cultures. The thing that is the same about them is they're within the same ontological, epistemological framework, but it means that any indigenous people are more like each other no matter when or where they lived on the planet, than any of them are like modern people or that any modern culture, no matter how different they are, are more like each other than they are like indigenous people or settled agriculture people.

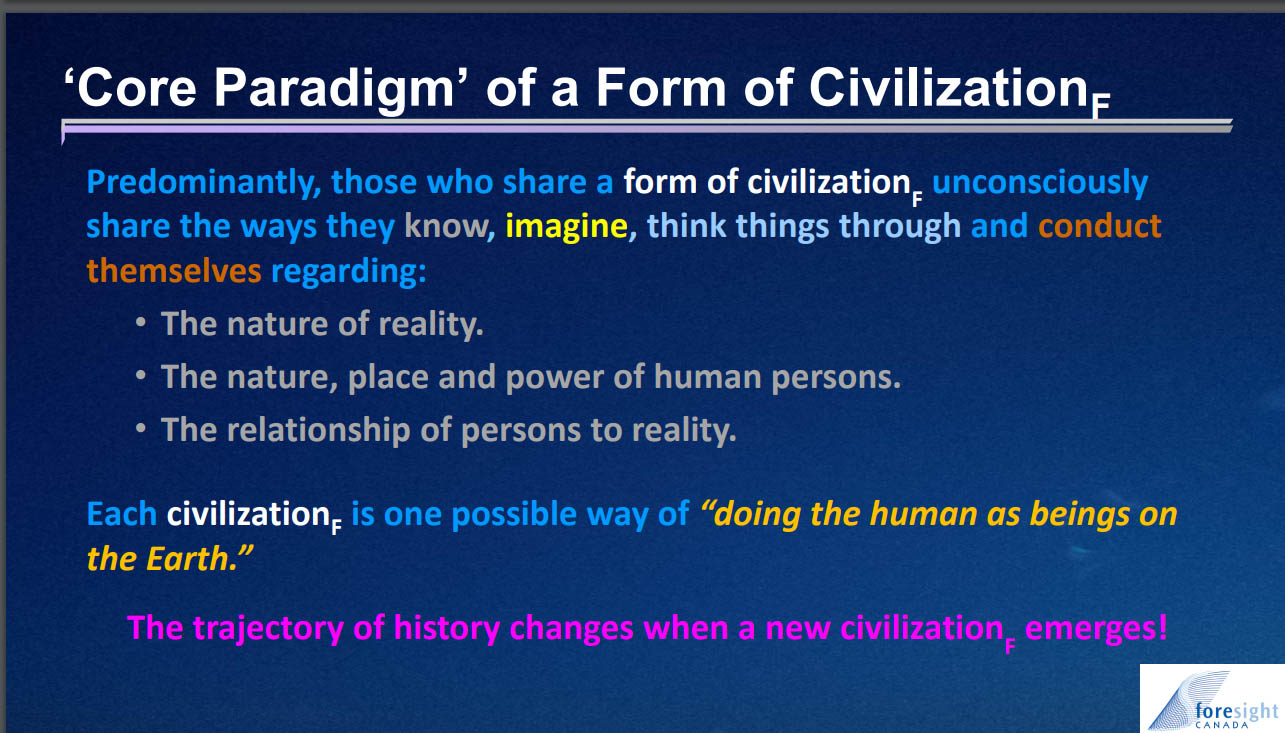

And the core paradigm are the critical insights into the nature of reality, the nature place and power of human persons, and the relationship of human persons to reality. And remember the content of those three things would be affected by and limited by and shaped by the ontological and epistemological framework of the form of civilization.

So this is becoming a technical way that we can begin to bring some care and precision to doing history and thinking about the present, let alone the future.

So we're back to these three forms of civilization saying they each have a distinctive ontological and epistemological framework with a distinctive core paradigm.

And of course the MTI globalization fantasy is that they will all become like us and if you've been paying attention to the business press, in particular, since COVID, you know that there are thousands of articles have been written about is globalization ending. That's globalization as a project, rather than simply the phenomenon of globalization, in the sense that we all know where everybody is now, so globalization as project is the sense that they all become like us.

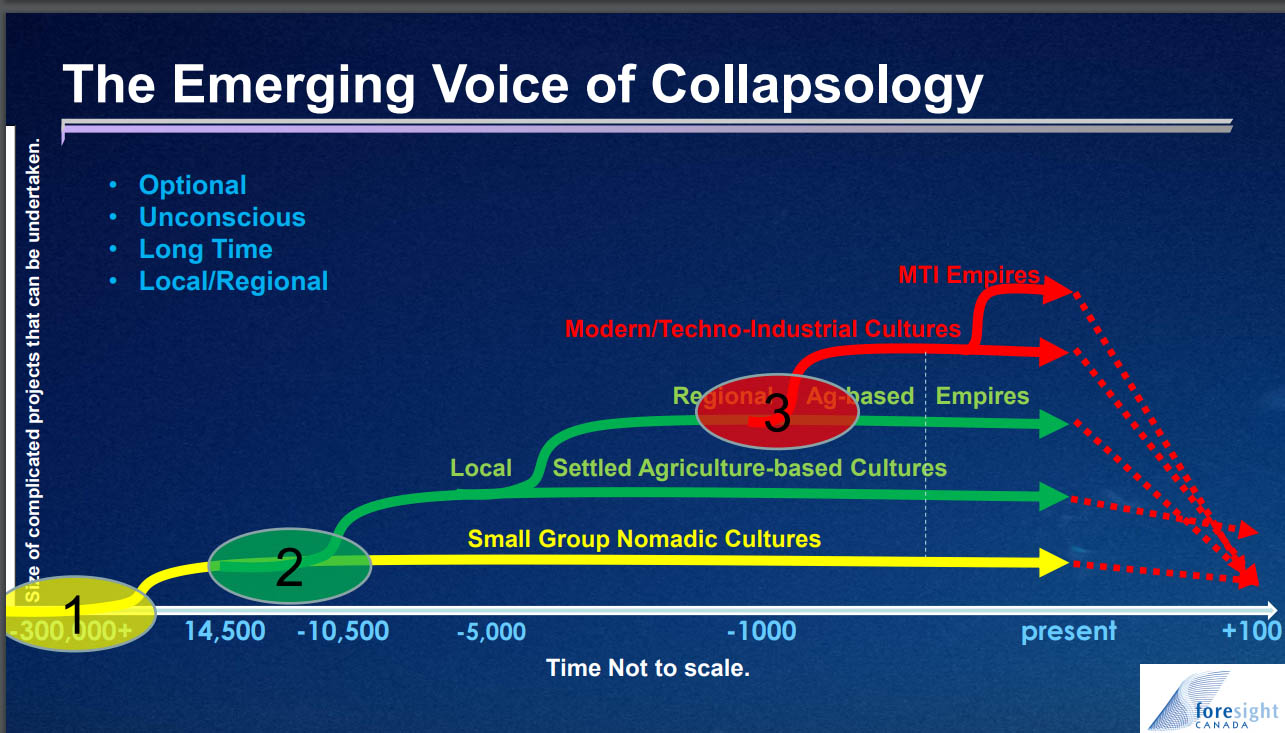

And the emerging voice of what is now apparently a new field, that it is being increasingly legitimized of collapseology. I didn't know that I was in that field 60 years ago when I began my work, but apparently I am. And it's basically saying I'm sorry your fantasy isn't going to happen, that you're past your best before date, and into irrevocable collapse. It will take a while.

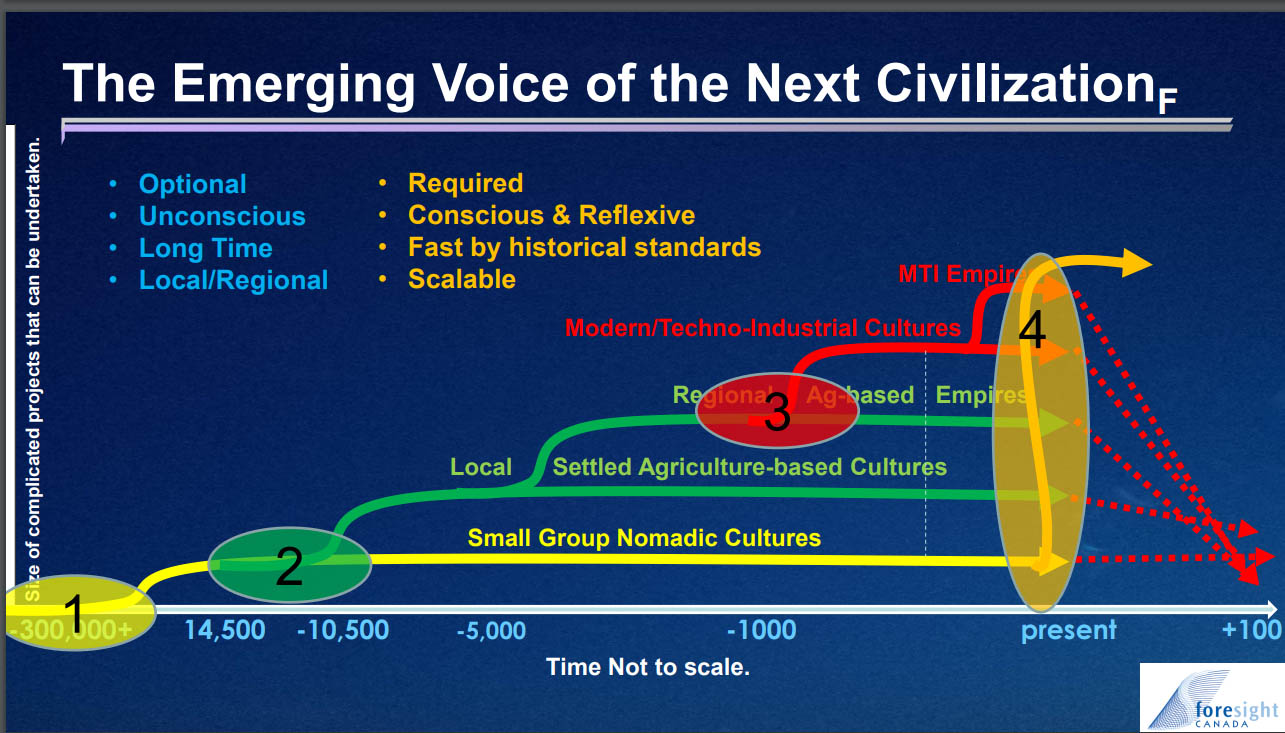

And then there's an emerging voice of people who say in this situation, where modernity is collapsing, think of it as a gift rather than a curse. Stop trying to hold it together the way everybody is running around now with their hair on fire to hold liberal democracy together because it's only as it disintegrates that there'll be enough space and enough doubts that we can think seriously about the next form of civilization.

And the trouble is that creating the fourth form is now required as opposed to optional. It has to be conscious and reflexive as opposed to unconscious. It's fast by any historical standards and it ultimately has to be scalable to everybody, so these are requirements that nobody on this planet has ever faced before. This is genuinely new historic work, so what else do we have to do?

Well, we have to create adequate mental models that let us think about these things in the same way that the Limits to Growth depended upon mental models that got expressed in computing power that allowed insights to emerge.

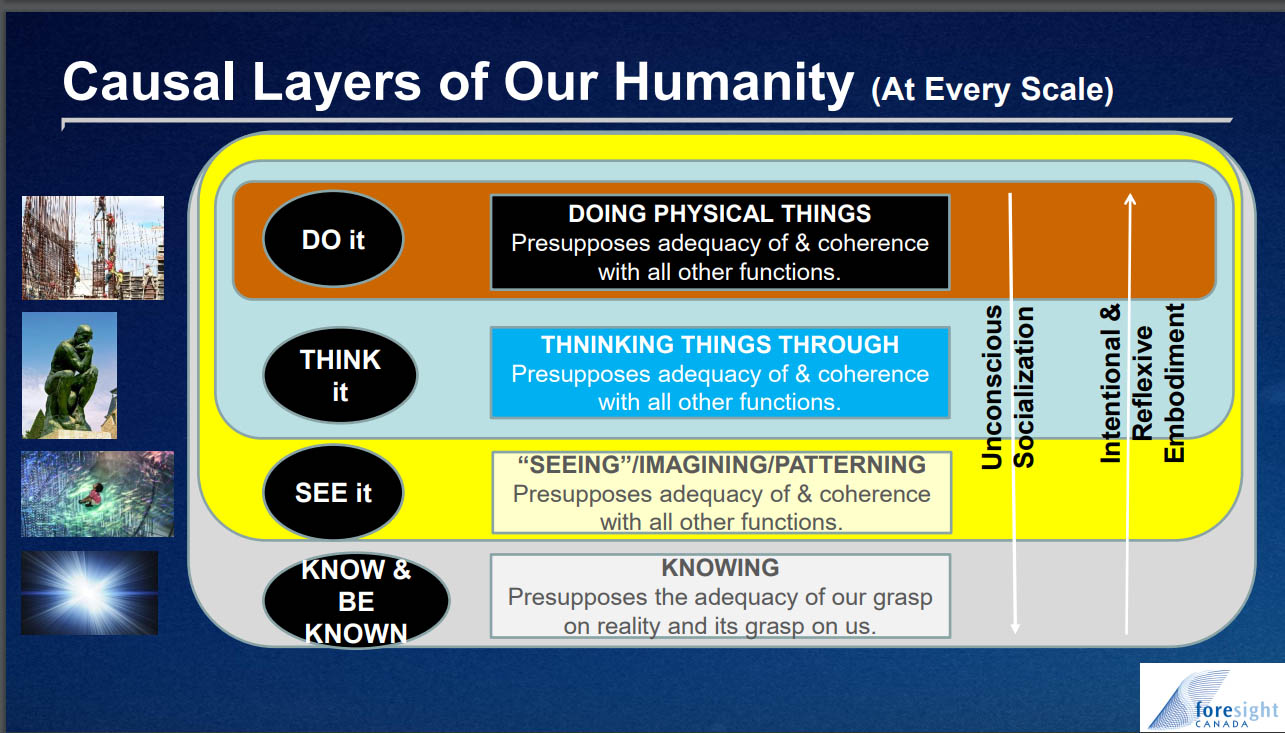

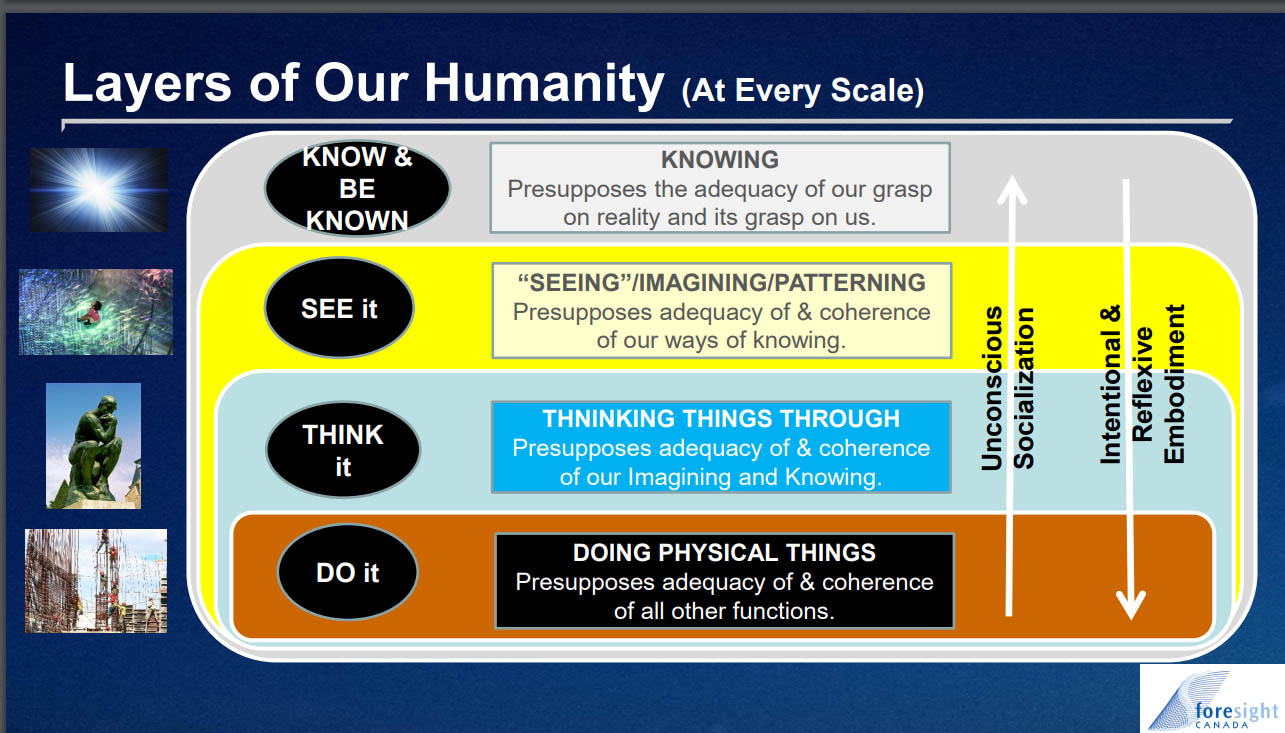

And one of the mental models we need is a causal layered model of human consciousness and culture, and if you're not familiar with that language, a causal layered model is simply an understanding of human consciousness and culture at different layers .

You can have as many layers as you want, and whatever model you decide to have, but it does mean that the model, that the layers, are causally related to each other. So if you change something significantly at one of the layers, it will eventually leak out and make changes in the other, because any consciousness or culture has to be reasonably coherent. There has to be some line of sight between whatever the four layers are. These are the four layers in the causal layered synthesis that I've developed over my lifetime.

There's also four layers in S Inayatullah's causal layered analysis and he has written about his model a lot more than I have. And if you're interested, you can google it. There are lots of papers and books about it. I haven't writ nearly as much, but these are the layers. That basically this is an image here of depth. Start at the surface with physical stuff. You open your eyes and your eyes stop at the surface of an object. You can't see any further, If you, if a wall is in front of you, you can't see the other side of it.

So there's physical stuff, but we don't just do things with physical stuff. We think things through. Now a lot of that thinking is about physical stuff, but it's also about other things. And what's more, we not only think things through, but we use metaphors and the logic of metaphors, and images and patterns. This is where Northrop Frye spent his life thinking about the structure of human consciousness at the bottom two levels.

And then the bottom level is how you know reality, how you present yourself to it, and your grasp on it, and its grasp on you. If you think that reality is the kind of thing that can grasp you, and unconscious socialization, which you learn about in sociology and social psychology, simply works from the top down, saying if you do enough stuff at the physical level, if you go enough, go to enough cocktail parties, even if nobody instructs you about the behavior of a cocktail party, you simply will pick up by being there and watching the physical behavior and whatnot. You'll eventually figure out how to think about cocktail parties, how to imagine them and therefore how to be present in them.

It also works the other way, that sometimes we have a blinding insight, a blinding revelation that changes much, and it takes a while to figure out what it means. So Watson and Crick in genetics, the blinding thing that allowed them to move on was the imagery of the DNA as a double helix. Before they had that image at the third level, they didn't know how to think about genetics. Once they had that image they could begin to think about it systematically and we could begin to do things. And of course that's long enough ago that genetics is powered on, but it's because something happened at that third level.

And of course you can turn that on its head and have high thoughts as opposed to deep thoughts, although deep thoughts seem to be winning the day in the sense that Deep Ecology emerged in the 70s, Deep Adaptation Jim Bendel's work in the last decade, and Deep Transformation is now being promoted by some and each of them is trying to say there's more to this than is just on the surface. And remember one of the features of an MTI culture is that it's systematically superficial. We privilege hard data over soft. We privilege the surface over you don't have to be a Marxist to think that the other levels, and the physical level, are just epiphenomenon.

And if you're thinking about the dominant storyline that the story narrative, that Bill talked about, the yellow, the indigenous way, they know they're living people. In a living civil, in a living reality, and therefore they're verb-based languages whether you're up the Amazon or on the plains of Canada, or the Malwa plateau of India with the Bil people.

And so the basic metaphors is that there are people in a cosmic dance with reality, with verb-based languages. Agriculture people, this is Aristotle, they know that reality is static and timeless and that they're in a play that is structured and scripted, and the roles have been assigned and the scripts have been written and all you have to know is the the basic lines of the play, what your role is in it, and to say, to play, your role authentically, and all the rest works.

In the modern world we're in a cosmic competition. not an accident that most modern languages are noun based, certainly English is because you win in modernity by having the most stuff, again bias to the hard data. And the next form of civilization of conscious reflexivity will be one of ongoing co-creation, and so it will use nouns and verbs, but it will use them intentionally and consciously.

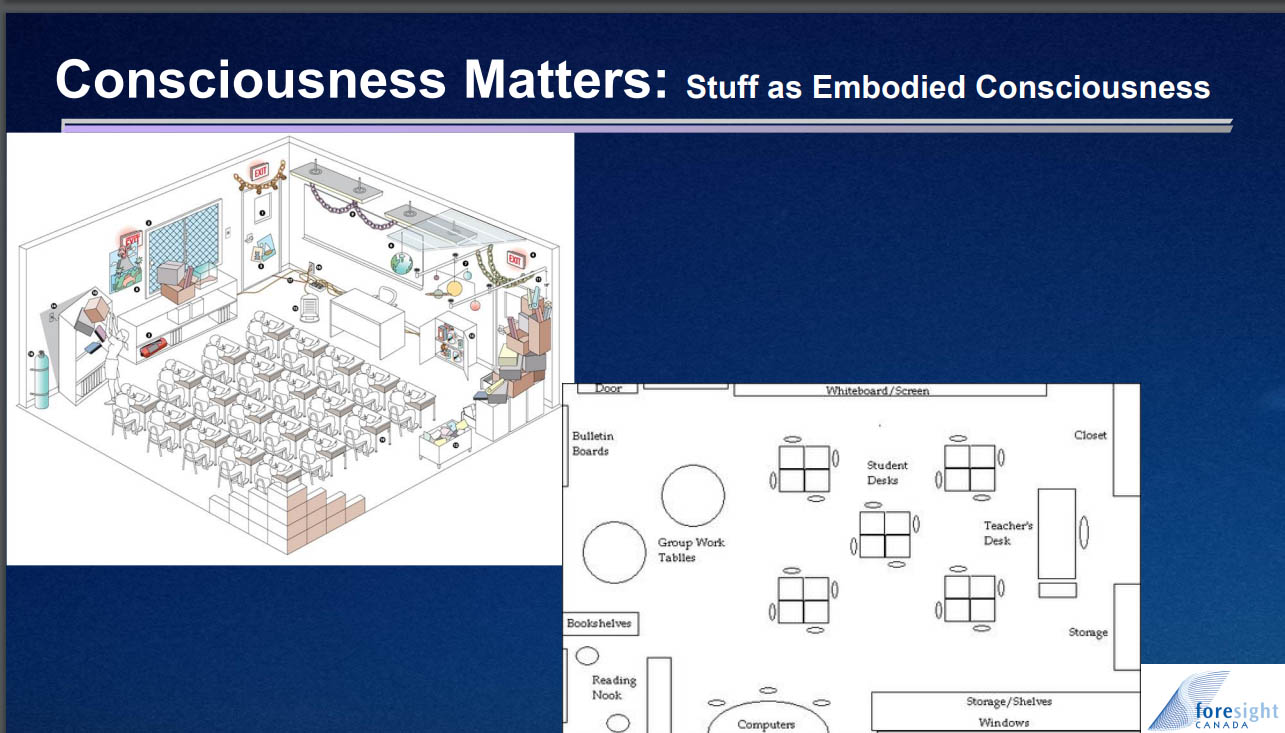

So what I'm trying to say with this little model is that consciousness matters. There's a third three-level pun there if you want to play with it, or that stuff can be seen as embodied consciousness.

So here's a picture of two classrooms and if I ask you which is older than the other, you know immediately which one is older. If I ask you to write even a short paragraph to answer the question 'how many people are needed in each of those classrooms for a student to learn?' The interesting thing is you can answer that question simply by looking at the physical arrangements. If I ask you to think about in which uh classroom are you likely to more easily be given permission to stand up and walk around if your back is stiff and you just need to stretch it, as opposed to seek permission from the teacher to get out of your seat. How does the role of the teacher differ in each classroom?

Here are four buildings on a landscape using my model. These are hard things, but they reflect a consciousness that says, given our consciousness and the metaphors that we use, and the way we think about it and express that consciousness and stuff that these are appropriate buildings to build on the landscape given who we think we are and what this earth is.

So the Stoney-Nakoda are top left, they're neighbors of mine, I live just over the left hand side of that image, Yam Naska is the mountain on the right hand side. It is sacred to the Stoney-Nakoda. I climbed up the back of it, up the back is just a long stiff walk, when I was 10 years old. I didn't know that it was sacred to the Stoney-Nakoda and nobody told me, and that this was offensive to them, but here's the Stoney-Nakoda when they use the phrase, 'all my relations' they know there are living people in a living human relationship to everything. You can see in that picture from the grass to each other to the hills to the trees to the mountains, the air, the clouds, they know you don't mess with reality.

Now if we come to Aristotle's Greece and the Parthenon, Aristotle also knows you don't mess with reality if you've studied any of his thinking, that's very clear because reality is fixed and given. It's created that way by the gods and we as human beings do not have the power or authority to in any way mess with it. All we can do is understand it more clearly, and then replicate it here on earth. So it's not an accident that the Parthenon is wider than it is tall because that shape of the front face of the Parthenon is actually, you can lay upon that the golden spiral which shows up in so much of nature. So that here is a building that is attempting to reflect the perfection of unchanging reality, which maps on to uh Aristotle's effect of keeping your elbows in and the golden mean.

So the Stoney-Nakoda and Aristotle would have things to talk about in that they would both say in their own language, 'don't mess with reality'. So by the time you get to Exeter Cathedral in the 12th century when it started, in the 15th century when it was finished, we're beginning to build buildings that are taller than they're wide and you can see there, even in Exeter Cathedral, that there's a sense of expression in that building that human beings, it may be all right to mess with reality just a little bit.

We may be more important than we've been taught at earlier times. It's not an accident that it was less than 100 years in Italy that the picture was drawn of man the measure of all things, man astride the world because you can see some of that here. And of course, in this tippy top of the skyscraper we don't even know how tall it is, but we know that it's not likely to just be 20 stories tall. There are 20 cities in the world that it could be in, so here we see that sense far more full sim in our modern world that we really are the measure. We run the place, and if I ask you, just given that, just knowing no more than that, but using my model of connecting physical stuff to deep insights, and I ask you which of these cultures are more likely to have an environmental crisis and which is least likely?

It's pretty clear the Stoney-Nakoda are least likely, and the folks in the bottom right are most likely, and sadly we're in the bottom right.

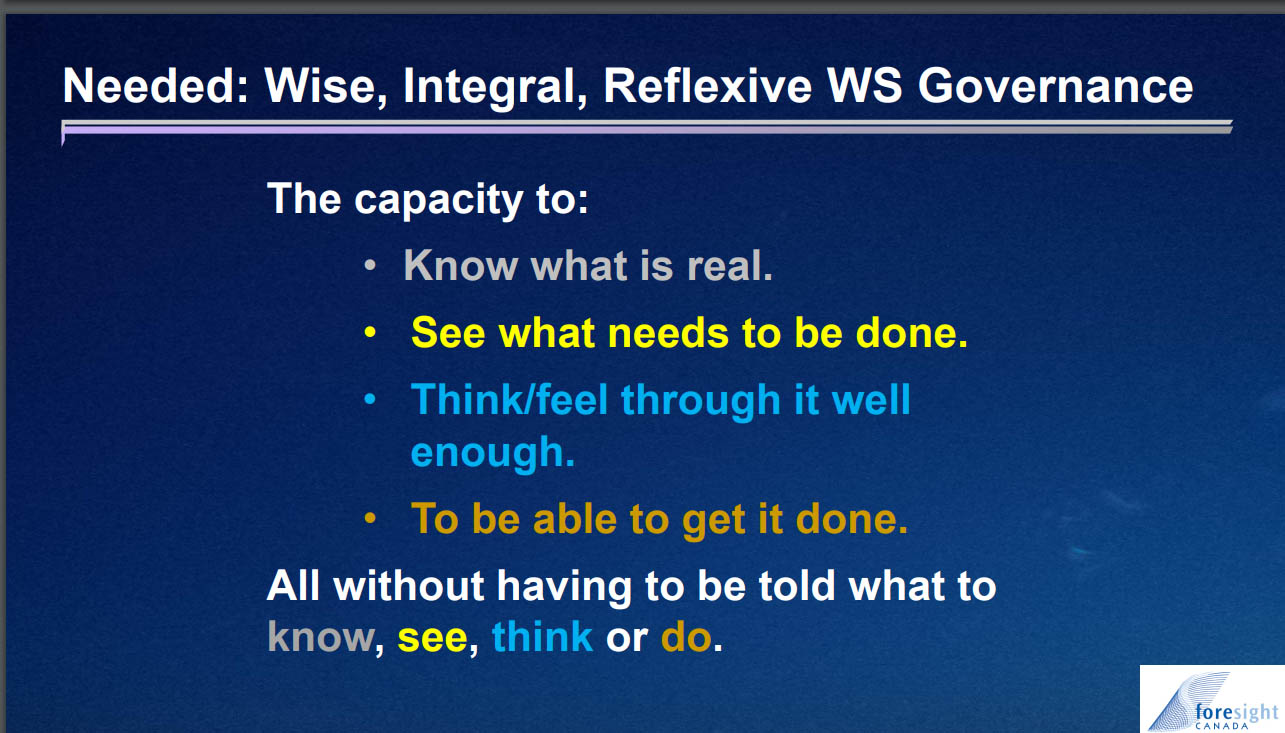

So what I'm saying is that we need wise, integral, reflexive whole system (is what ws stands for) governance.

Back to this model, the capacity to know what is real, to see what needs to be done, think and feel it through well enough to be able to get it done without having to be told what to know, see, think or do. And there isn't a government in the world that meets that standard.

As Yehezkel Dror said 21 years ago, the situation of humanity in the face of global transformations can be summed in two sentences. "Societies are unprepared. Governance is unequipped." In the main, contemporary governance is obsolete and enable the field to deal fittingly with rapidly mutating problems and opportunities.

And I agree, but you see, if you have the model that I use, you can read those words picking up Bill's sense that we have some very deep learning to do about the very way we know reality and the fundamental metaphors and their logic by which we interpret it, whereas if you read it with a normal MTI mind, you read it kind of at the surface and say, 'yeah yeah yeah', and then get back with that male arrogance that dominates MTI cultures. They get the hell out of the way. We know what we're doing and we'll get on with it, which is to say we learn nothing.

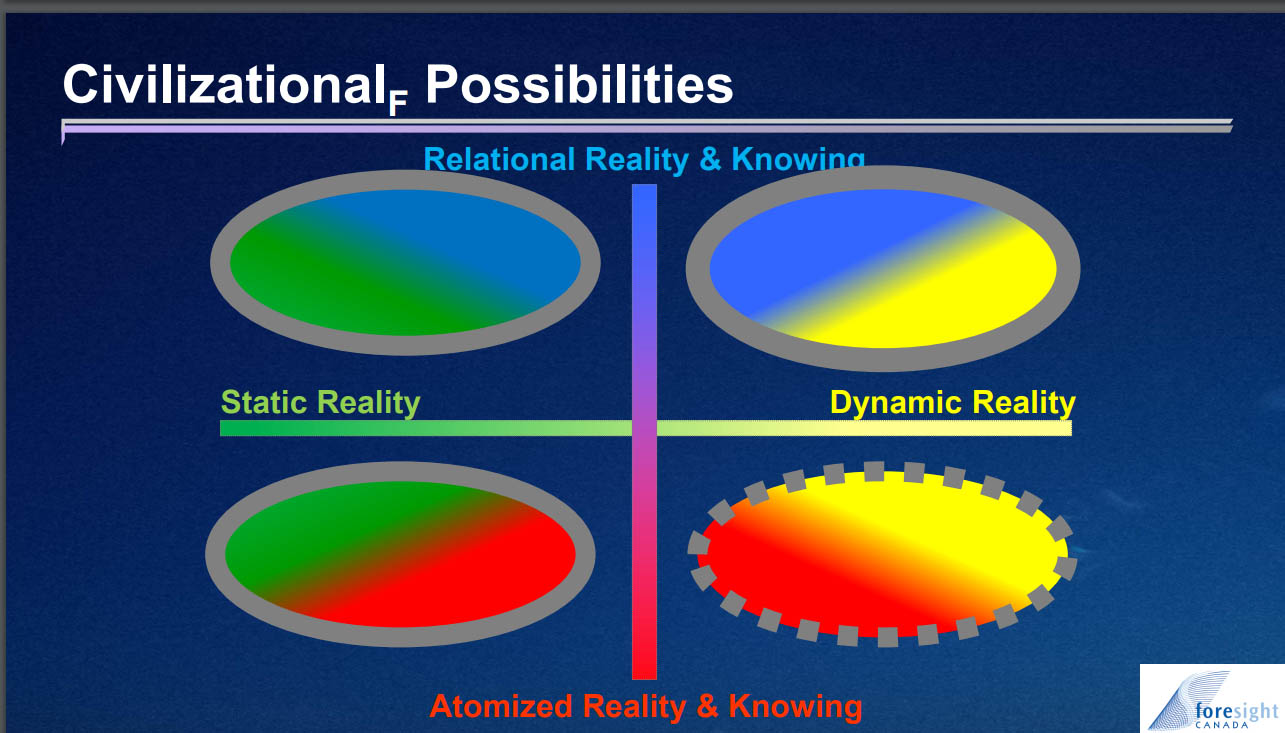

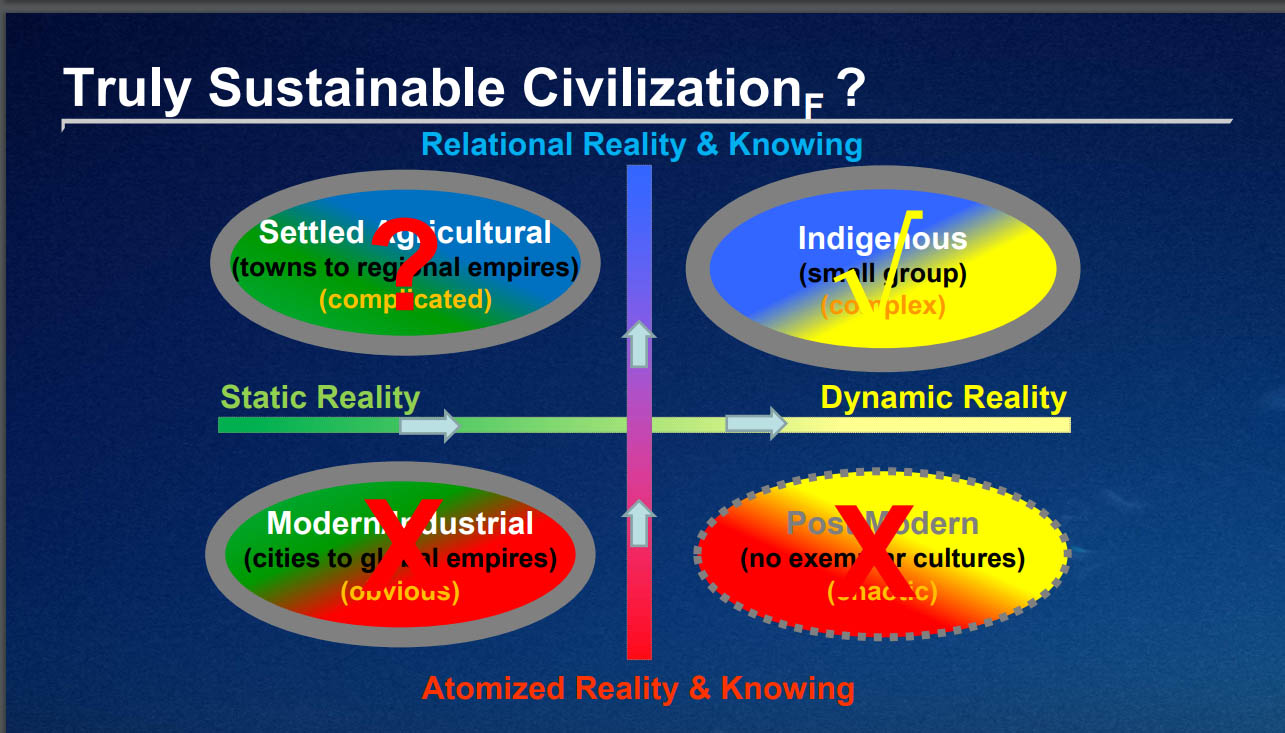

So what else to do? Well, we need to create adequate mental models. Another model we need is to create a way to differentiate one form of civilization from another,

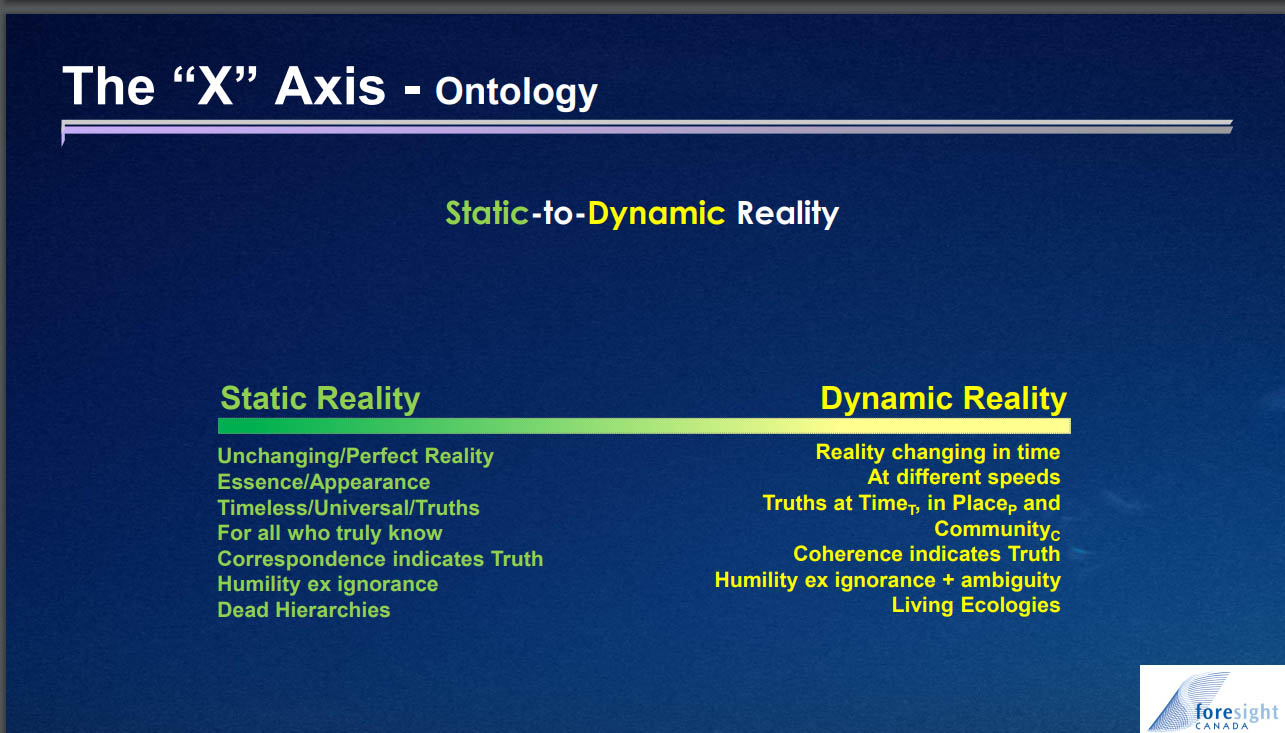

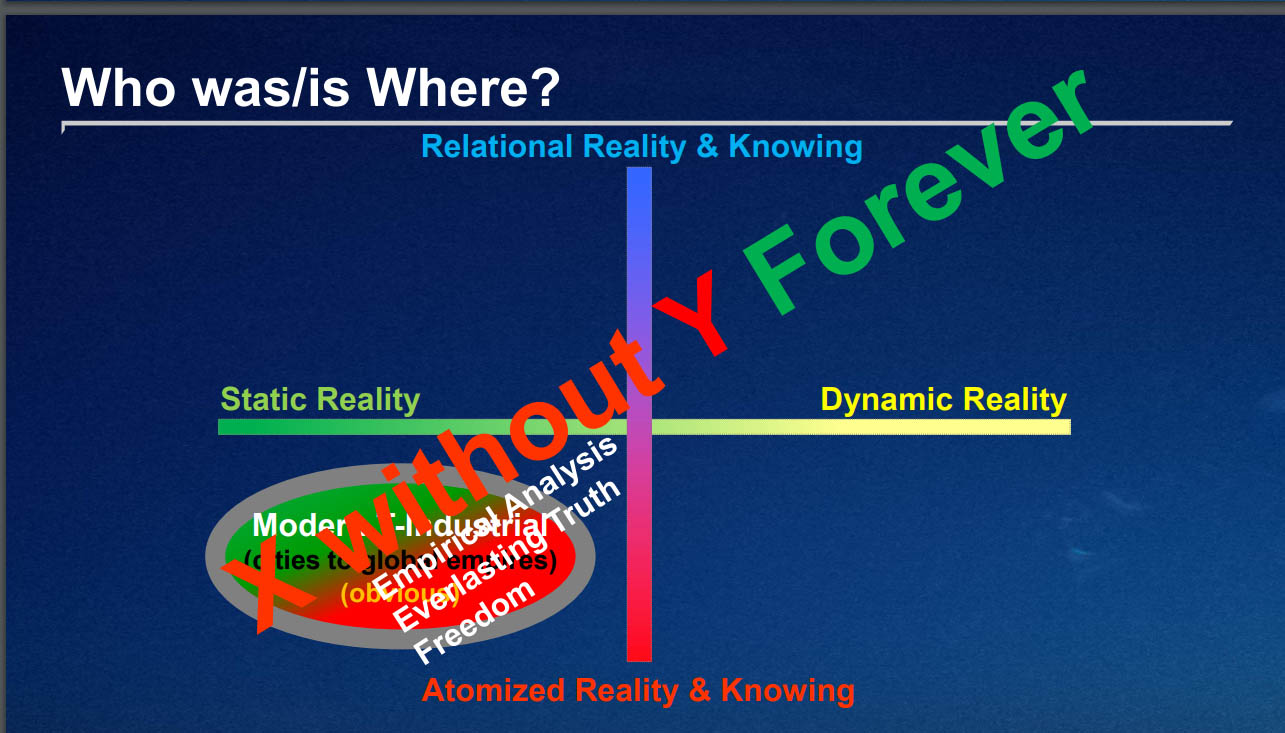

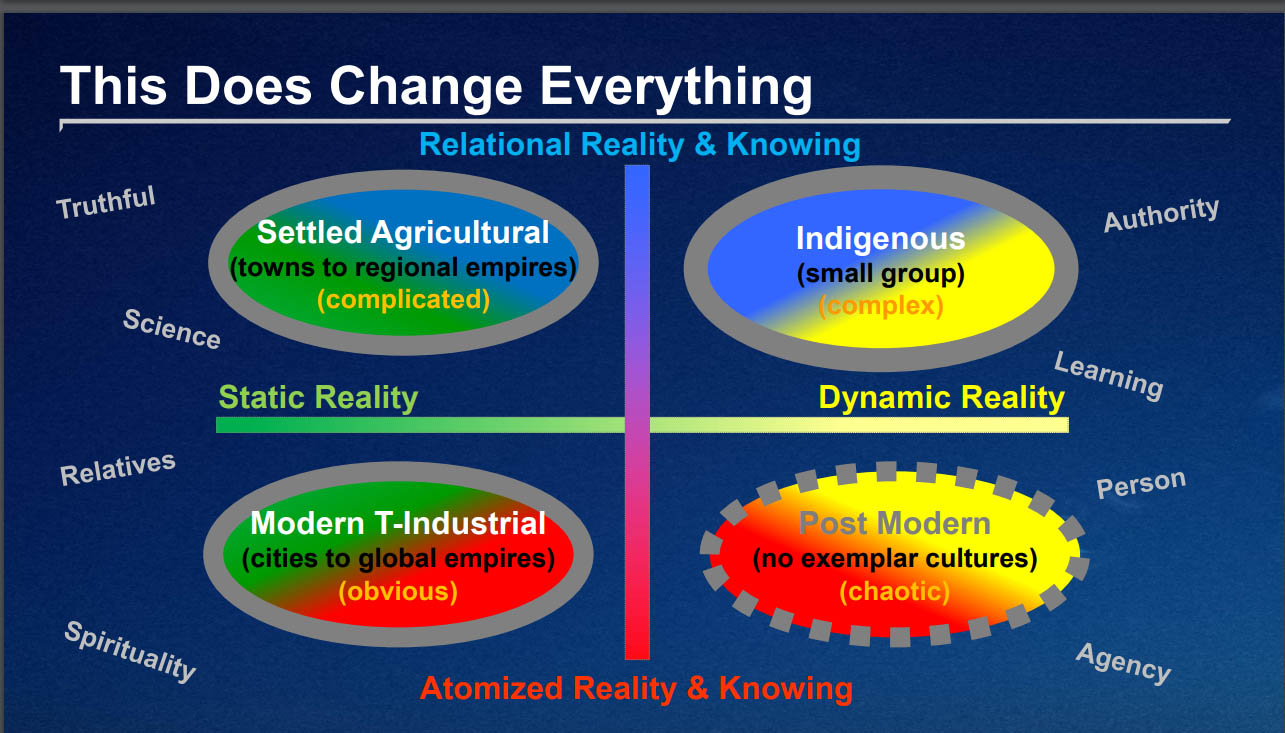

and so this is just a simple two by two matrix. The x-axis is ontological. It's about the nature of reality, and on the left-hand side you were the Aristotle, that reality is static, that the really, real does not change now things appear to change, so that's why you need, in a culture that's at this end, the distinction between appearance and reality. It's why reality can be perfect. So here, in principle, knowledge could be perfect and if your knowledge is less than perfect, it's simply out of ignorance in the sense that there's too much to know and you don't know it all yet, or you've made a mistake in observing reality, but in principle knowing can be perfect.

There's no ambiguity in it and so what you get is truth, is timeless, and forever. You get propositional truth emerging here because the same truth has to be expressed in different languages, which is why we say the same proposition is expressed in different languages. The languages may be different, but the proposition is the same, which is why the Catholic Church has propositional revelation and you have the correspondence theory of truth, that truth corresponds to reality.

At the other end reality is dynamic, it changes in time. It may not all. Some reality may change in nanoseconds, others in hundreds of millions of years, or even billions. So, it's at different speeds, and so you get different judgments about truth at different times in different places by different communities. Change any one of those, you get a different judgment change. All of them. You'll, of course, get a different judgment.

So here, coherence is how you judge truth. And humility is built into this, not merely because we might make mistakes and be ignorant, but because of the nature of reality itself. It is inherently ambiguous. Knowing here cannot be knowing here, is freighted with ambiguity, and you're dealing with living complex ecologies.

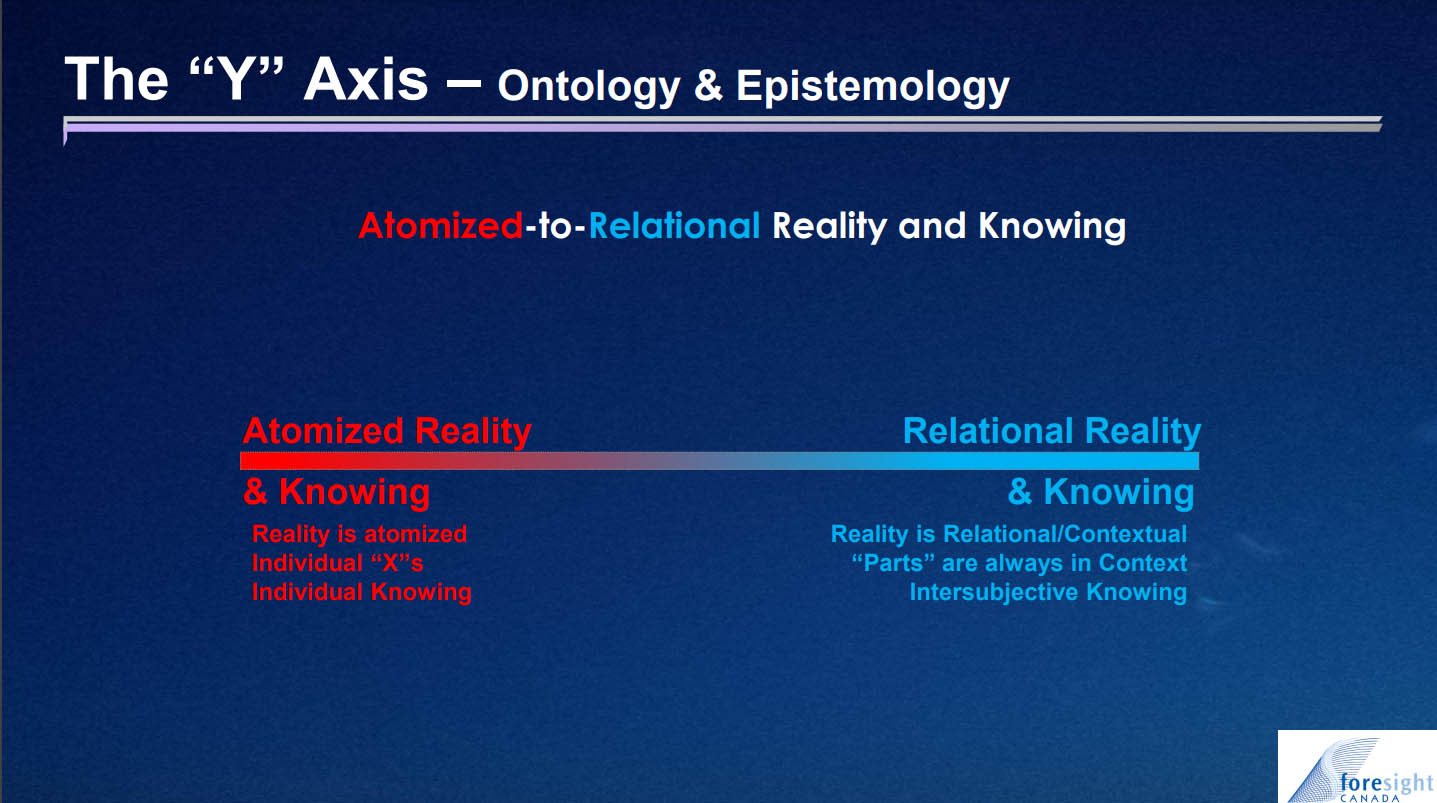

The y-axis at the left-hand end you have atomized reality. That is, you're dealing with a thing that can be broken down into its constituent parts, and you can then break each part down to its constituent parts, and its constituent parts all the way down. You do that with persons, you take a community and break it down into individuals and, as Margaret Thatcher said, there's no such thing as society, there's just individuals. So we know where she is on this and what's more, this is an epistemological axis, because individuals can know adequately all by themselves. They don't need anybody else. Leibniz's windowless Monads are on this left-hand end.

At the other end is relational knowing and reality, so reality itself is seen as relational, that if I look at this watch, if you want to understand what a watch is, and why taking watching time is so important for modern people, you can't understand that all by itself. You have to know all kinds of other stuff that relates to this artifact. In order to answer the question in what may be a history exam or a sociology exam, what is the significance to modern culture of mechanical watches? And so parts are always in context, and to try to understand something by itself.

So good futures work is context is king, and to do it in a perfectly modern way is to fail. And knowledge is an intersubjective project. If you insist on knowing things that no one else on the planet knows, that no one else in your community or your culture knows, the human response everywhere, always, is to shun you to the point of death, or kill you.

So these are fundamentally different. You put it together and you get, here's that heavy gray line again, that's the ontological, that's the boundary, that's the framework, so I'm saying that cultures can be in these spaces, but a culture in any one of the spaces is a culture that only fits within the definition of that space.

So a culture, in the bottom left, that static reality and atomized reality cannot be the same culture. That would be in the top right, or in any other space, so that these frameworks and characterize and shape and limit what's possible there, and this is why this is important, because you can then tell human history in this.

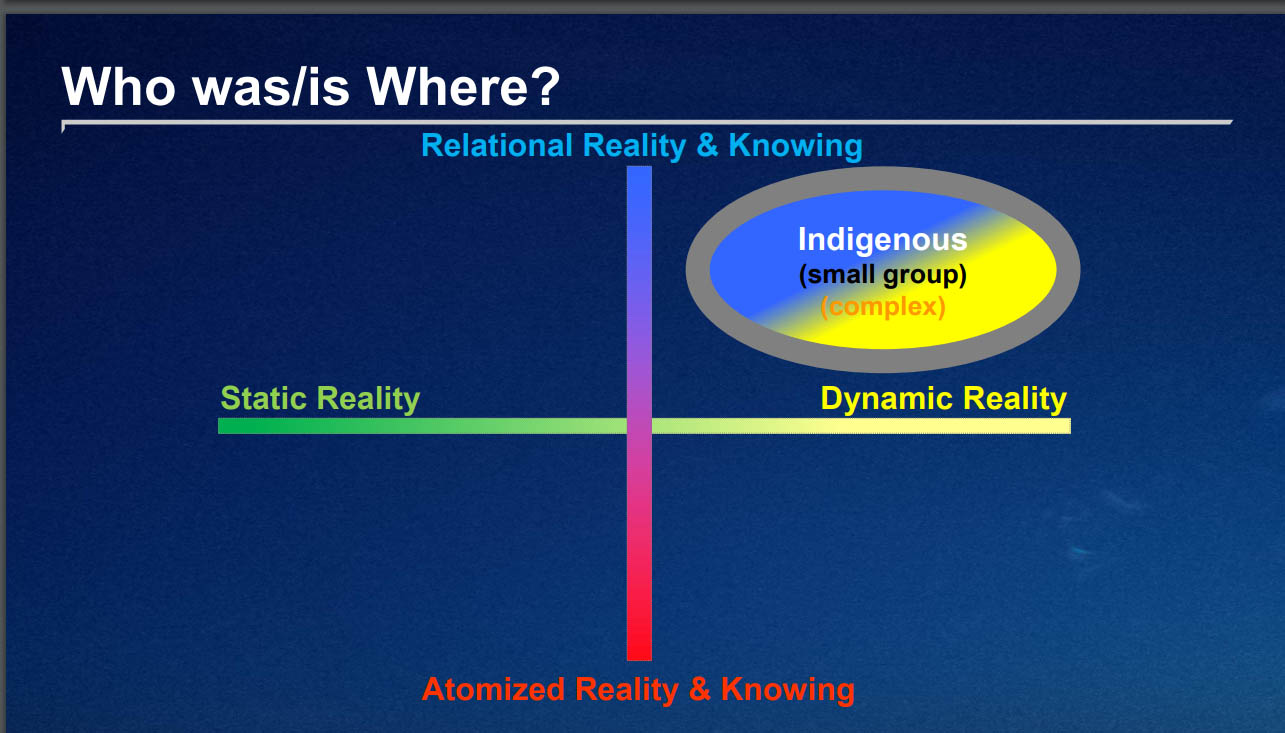

That here's where we started 300,000 years ago. That we became distinguished from our great ape ancestors because we learned to live in groups of people larger than any of our great ape ancestors.

The Dunbar number is 150, and so we had small group indigenous people, and the interesting thing is that the word in orange there is complex. If you know David Snowden's Cynefin model, the words in orange pick up his work that these people handle complexity better than in any other space because they're in a living universe themselves. Living in a dynamic universe, the whole place is complex and therefore they manage complexity. One of the ways they do that is to live in small groups, because once groups get too large, the fact of complexity causes all kinds of other trouble.

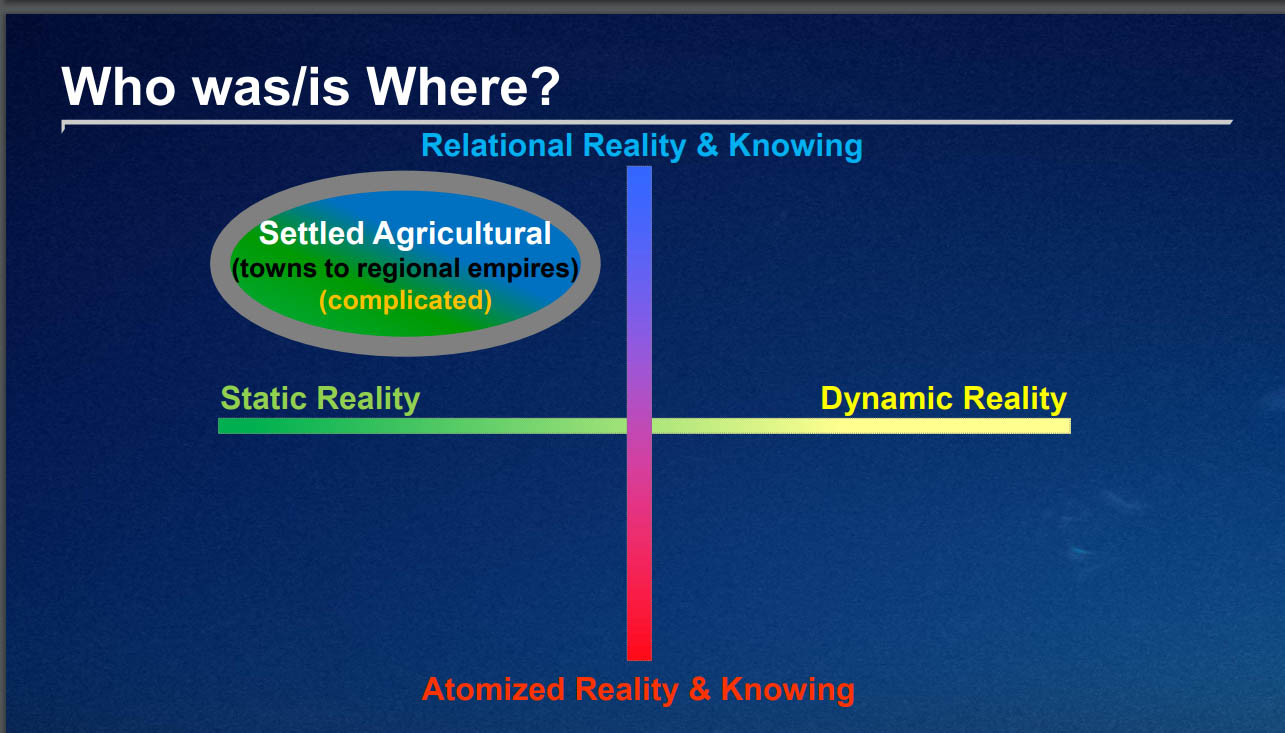

Eventually, with the Holocene we drifted over and it took a while, and there's lots of things happening in between, but eventually, as this model settles out, what was used to be a complex reality becomes merely complicated, because here, remember reality is fixed, and given the parts don't change, and so you've got an extraordinarily complicated byzantine world, but it's fixed, and it's structured, and so this is the world of Aristotle, this is the world of the great chain of being.

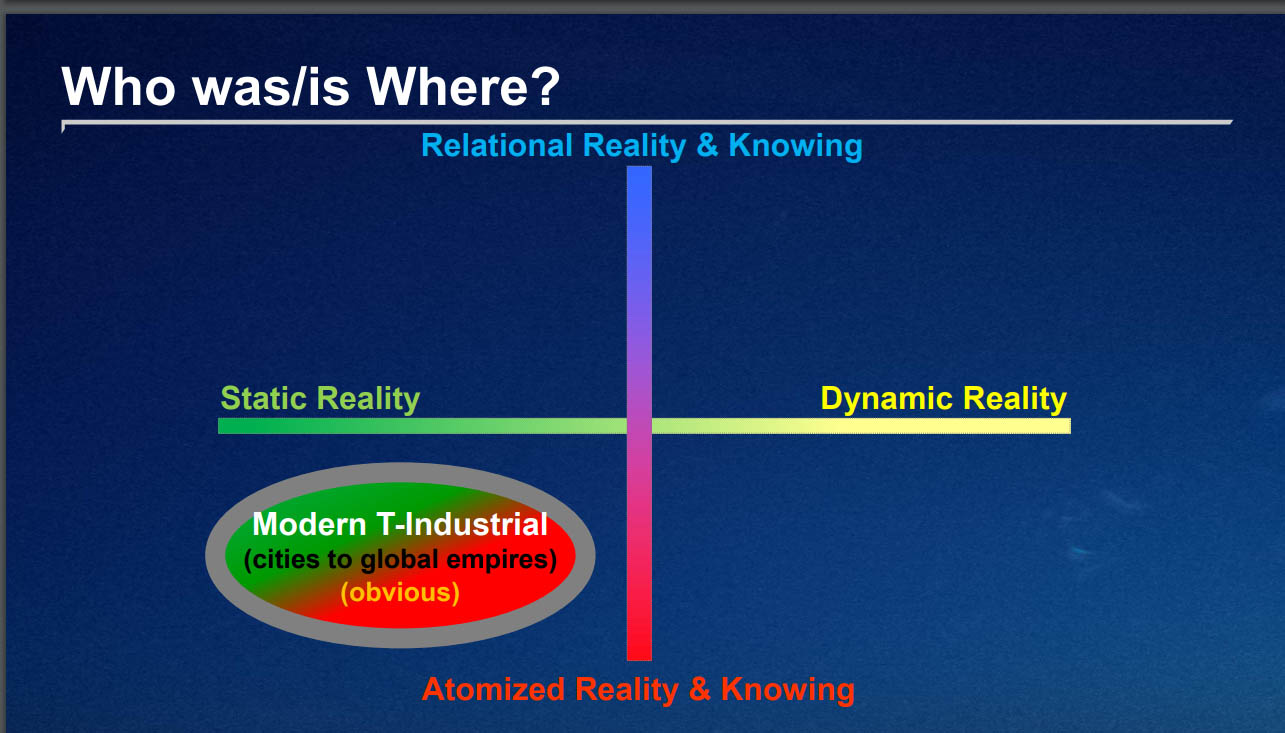

And all we've done in the last thousand years, those of us who became modern, is kind of work our way over the last thousand years, you can see it early in art and architecture and poetry and music, in Europe, and eventually it becomes so obvious. I mean, if you ask people when did the industrial age start, a lot of them say with the steam engine. Well you're 1750. That's nice, and obvious. You can trip over it. It's bloody obvious, and... but you can't pass a history exam if that's your answer, because historians know how to deal with subtlety, at least, and know that you don't get the steam engine until a whole host of other things are in place.

You need original conditions for that to happen, and so here we privilege the obvious, literally the bloody obvious, is more important than the blindingly obvious. As scientists smile to themselves they say with, great pride to put down the rest of us, that anecdotes is not the plural of data, and you know you've been put down by first enlightenment science, and one of the interesting things is first, in the the insight, is emerging among us not yet a dominant thought, but there are formal global organizations now exploring the thought, that what we need is a second enlightenment with second enlightenment science, because first enlightenment science is in its original form part of our problem.

So the heart of MTI is you can have x without y forever, whatever x and y are initially. With Augustine, he's with Aquinas, it was you can have the earth without God, and then we said you could have chemistry without philosophy and theology, and we said you could have chemistry without the history of chemistry, which is literally true.

Lots of PHDs in chemistry know nothing about its history. Empirical analysis is the great thing. We have everlasting truth, and human freedom.

And this is a model that picks up, first enlightenment, the world is divided into the objective and the subjective. The objective is within that yellow frame, and it gets fixed and ordered, and if you look at it as an icon, it can be the street pattern of downtown Calgary in which the streets go one way and the avenue is another. It can be an apartment building with the elevator on top. It can be a classroom and if you have to ask who which one is the teacher you're in trouble.

It can be the military lined up. It can be an org chart, much of the official modern world is organized in that imagery, but once you're at home on your own you can do what you want, you can play canasta, or square dance, or just sit and read, or whatever.

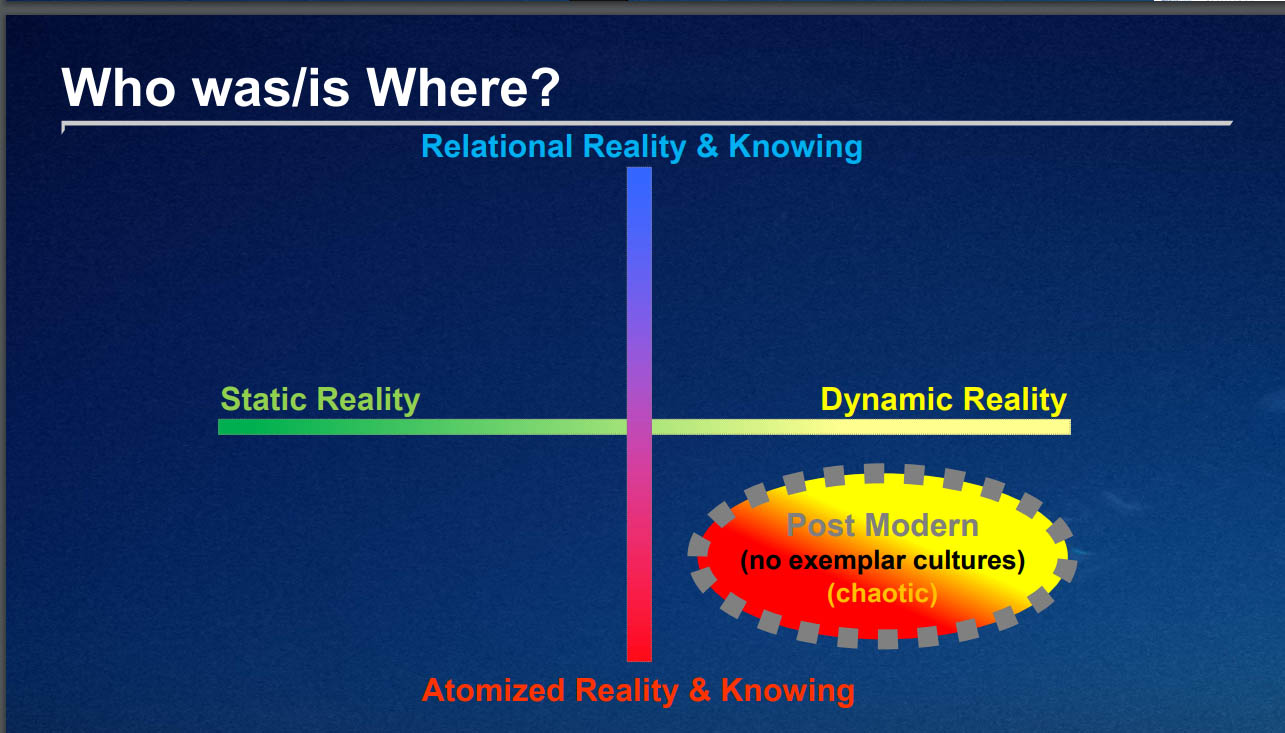

That last space is, the postmodern space, and you get no cultures there because in a genuine post modern space there's not a basis for authority that's strong enough to tradition even your children, let alone create a culture.

So then you apply these concepts, and what I'm suggesting is it literally changes the way, a fundamental way, that we tend to read history.

We tend to use the language of art or religion or science as if it's the same throughout history, whereas this is a reminder that if you're talking about art in the indigenous space, you're talking about a very different thing then you're talking about it even in settled agricultural space, let alone modern space. The same is true of religion or science or truth or authority or learning or what it is to be a person, and therefore if we don't have a model like this we systematically misread history.

Boom, and we're at one hour and we'll let you go on a little bit longer, and also ask people to please put questions in to the chat, so that we can have things ready for Ruben when we get to him, answer him, and answer them.

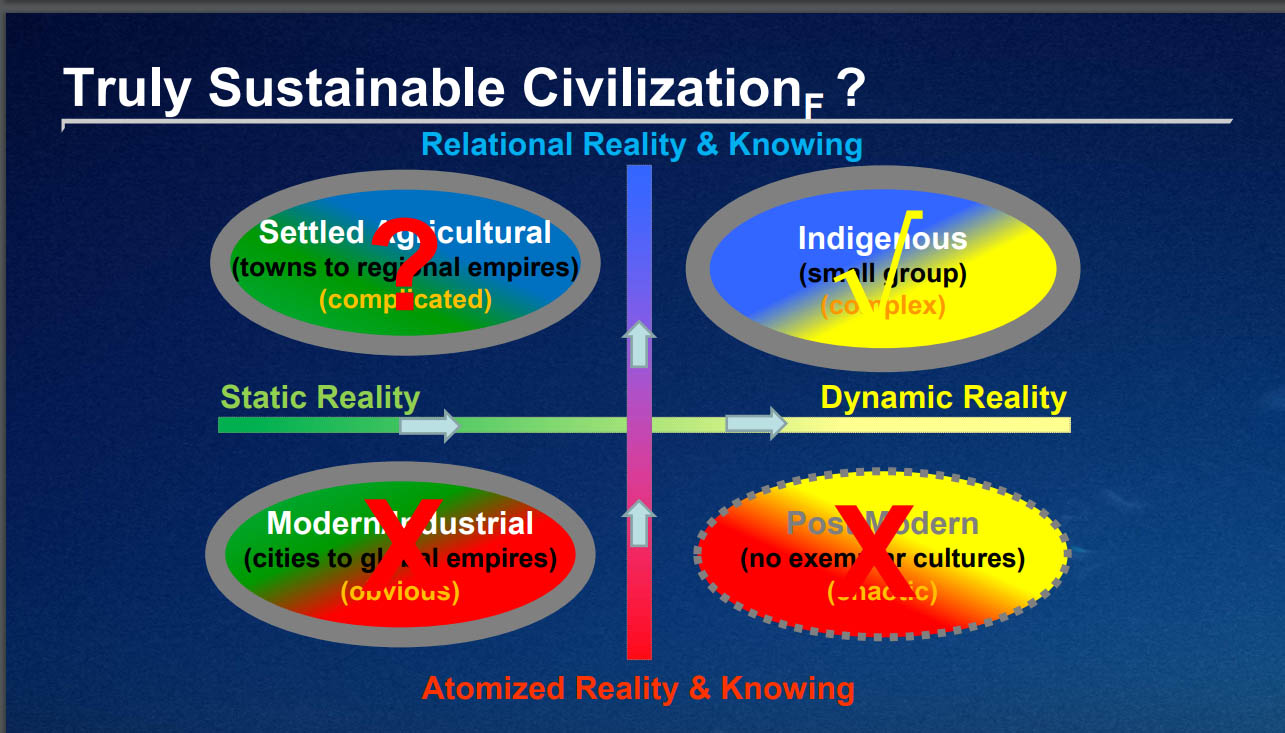

Yeah, we're almost there okay. Now if you ask which of these cultures is truly sustainable, obviously a post-modern culture isn't. You can have a most postmodern mentality, but it's interesting that most of the people who develop most potent thought have their feet squarely in the bottom left hand side, so they get a paycheck from the university. They are not postmodern in an integral sense, and it's even the case, as Bill Rees and increasing amounts of research tell us, that our, our modern way of living is not sustainable, and we should stop trying to make it sustainable.

The top left is a question mark because if you organize it, the way Putin, this can be a society that will be highly structured. There will be layers of authority very hierarchical and if the hierarchy is led by a tyrant, it may well be unstable enough that it's not sustainable, so Putin is in more trouble than the one of the Czars would have been who was more respectful of the Russian people, and of Russian culture. Putin claims to be, but he's really tied up with himself.

The place that is authentically sustainable is the top left space. That is, that's the ontological and epistemological framework you want to work in if what you're working towards is a form of civilization that is sustainable, but I want to remind you that that is about persons, and humans, which is why I find the language of an ecological civilization offensive, because it downgrades humanity, and to that extent it's still got some of the hangover of modernity, which also downgrades humanity.

So here's Brian Goodwin, one of the godfathers of complexity, reflecting on the significance of complexity theory, saying scientific knowledge originally seemed to make possible the prediction and manipulation of nature.

All true appears now to be pointing towards a new relationship with the natural world based on sensitive observation, on participation, rather than control, and my point is that if you read that in a normal modern frame of reference, you simply read it as kind of good advice: don't beat your dog. If you read it in the kind of framing that I've developed, you see Brian Goodwin in his own way coming to understand that we need a new form of that we need to learn to approach the whole of reality, the way we approach our child, or our lover, that is with acute observation, wanting participation rather than control.

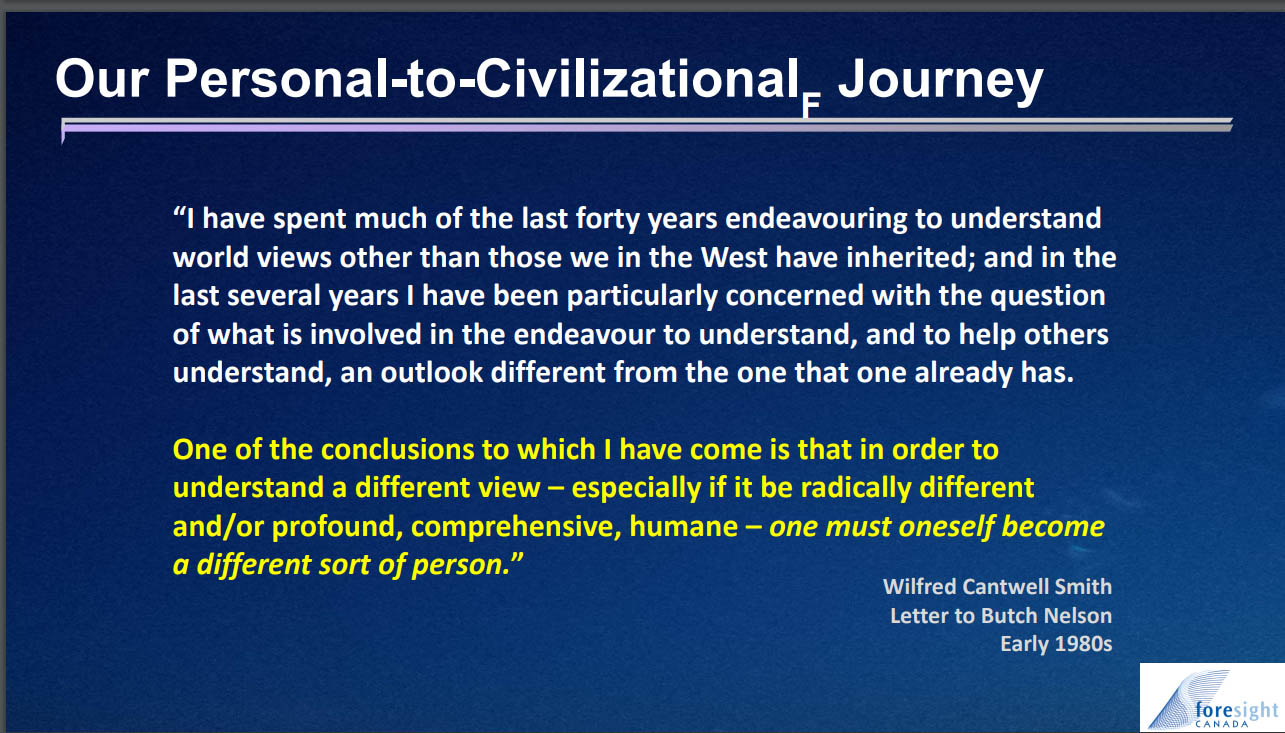

Wilfred Cantwell Smith, great historian of religion, Canadian, died in the year 2000, wrote me a letter in the early 1980s when he was the head of the founding head of the Harvard Institute of the Study of World Religions, saying, Butch, which is how he knew me, I've spent much of the last 40 years endeavoring to understand world views other than those that we in the West have inherited, and in the same, in the last several years, I've been particularly concerned with the question of what's involved in the endeavor to understand and help others understand an outlook different from the one one already has. And one of the conclusions to which I have come is that in order to understand a different view, especially radically different and or profound, comprehensive, humane, one must oneself become a different sort of human.

And I again invite you to hear that in light of the formal structures that I've laid out for you. It says that as long as we're doing the history of religions, as with a modern first enlightenment scientific mindset, we're going to get it wrong. It also means that if we need a new form of religion, a new form of civilization, that we are involved in this as persons up to our neck, and to in any way pretend that we're not will be not just personally offensive, it means that we'll be getting it wrong, and increasing the chances of death, so finally, then what else to do?

Cooperate with the reality of personal to civilizational, a personal to civilizational journey. If you look at what we're learning from science, and the arts, we are slowly being nudged left to right on that axis and bottom to top and if you look for it the evidence is overwhelming.

So the core work of the 21st century, I'm arguing, is literally to learn to know and imagine and think through and respond to the actual situation that we're in, and that is that our form of civilization has no long-term future, and that therefore, to consciously become consciously co-creative, and reflexive persons and cultures, so we're replacing MTI with CCR, so says he as if he knows what he's talking about. Thank you, and over to you.

Thank you very much, Ruben, if we don't have something to think about now, we are not listening. That was very, very challenging. I'm gonna start being the interlocutor. I get the first question and it's pretty hard to figure out which one would be most productive, but there's one before we go on to a very good list of questions emerging on the chat. It strikes me that it's got to be a real challenge to identify a not impossible future that we could all, in some way, get people to work together to achieve, and I, so I have two questions from that.

One is, is it therefore possible to define such a desirable outcome, and secondly, how the hell do we get people to actually try and move towards it? And those are pretty big questions. I'm sorry, but,

Yes, they are, and if the model amounts to anything, I should be able to say something other than gobbledygook, and I mean no offense, Ted, we've known each other a long time, so the offense, but the way opposing it is the perfectly normal way that modern people think about the future. Right, we know where we are and we have to have an image of what it is, not this, what if not, you know, when actually the model suggests that's not the way to do it. It's not the way it happens. Ihe model suggests learn to dig under and get a feel for, and there's a simulation game I've developed that we could do sometime that, literally, you can begin to get a better feel for the feel of what it is to be modern, and the feel of that top right hand corner, which is what I'm saying we're just stumbling towards.

It's not as if we just all are going to become like the Stoney-Nakota, and as their forefathers did, heat rocks and put them in a pot to boil water, but that's the epistemological and logical space, and if you understand that then what you're looking for is teaching people in their own life, in their own personal experience, in their own relationships, in the reading that they do, in the novels that they read, we're getting them to develop the cues to see the ways in which the modern world is really deeply modern, that it really does reflect the assumptions of that bottom left-hand corner, because that's comforting in a way that we're actually learning who we are, but we're also can see the way in which we're struggling towards so that people who talk about community, you see a lot of that, saying that community matters, that we have to go local for all kinds of reasons. If you know the model, you can help teach people that communities are inherently relational so that any move that is inherently relational, whether you're doing it in theoretical physics, whether you're doing it in terms of energy grids, whether you're doing it in terms of human relationships, any move that is more inherently relational is a good move, and so what we're going to be doing is journeying and getting better at doing the journey into space that is more relational and dynamic, and we won't know what it is in a sense until we've been there and live it for a while, to say, oh, this is what it is kind of writ large, but that's generations ahead of us

Thank you very much Ruben. I'm going to go next by the way I, we just tell you one thing we've been working on a Club of Rome thing several of us, some are here today, on the whole idea of how on earth we define what a survivable culture with well-being really looks like, and I'm not going to tell you about it now, but we are struggling to try and do either to both define it, and perhaps measure it, and at some point I would like to talk to you personally about that, but I'm going to turn you over now to Anitra Thor Hog who's next on our list. She's also one of the members of those of us struggling together to try and address this thing.

Anitra: Okay, I'm struck with the fact that the most adaptable, and the most conceptually changing, is if we saw ourselves as part of the array of the ecosystems of the globe that we live in, including the chemistry and physics of what propels the ecosystems, and I'm wondering if some kind of oscillations such as they have in atomic physics, between the top two, the agriculture and the nomad, wouldn't be a space in which, if we saw ourselves in terms of the ecosystem, we would be open and adaptable to finding new ways of living, and new systems, and what I particularly am asking about is, how does regeneration come into your model because we have gotten rid of 85 percent of the forests of the terrestrial area, and about 50 percent of the plants in the sea, and we haven't taken our responsibility for caring for the other parts of the ecosystem, and regenerating them, and I personally think that's a part of these final solutions, so I'd like your wisdom on this.

Well, it's a wonderful question, the, if you if you think technically, in that bottom left-hand corner, can you, what kind of a model do you have of regeneration if you're living in a mechanical universe, and the answer is you can't do regeneration in the bottom left-hand corner. That regeneration, insofar far as biologists are now talking about regeneration, they are no longer doing first enlightenment science. Insofar as people are talking about living systems, they're no longer doing first enlightenment science because first enlightenment science is about an objective world that's dead, and so regeneration is easiest done in the top right hand corner although you might get a version of it but it would be, not really regeneration, it would be more reconstruction. In the top left, in the top left hand corner where the pieces get reorganized, and you, and you would, you could do reconstruction in that sense in the modern space.

The place where you could do, where you can say authentically, as many people are trying to say, as a person, as a human animal, we who are animals need to understand that we're part of the biosphere, yes, if you say that in the top right hand corner it's easiest to say that and explore it more fully than in any other of those quadrants.

And can I ask you to put that, that slide up, because you've been referring to it, and I'm not sure if everybody could help if we could have that on for people to see, as you refer to it.

Sure, I'm sorry, I just wanted us to be able to, faces no that's fine, we can throw that one on that will help a lot, so I mean there you are, the metaphors of a modern industrial world turn out to be mechanical because, you're dealing with unchanging reality and, and it's in bits and pieces, so it's an objective world that you can examine under a microscope that the metaphors at the top left are dead biological, they're more biological they're because the top bar, the top two, you're a systems thinker because if you're a systems thinker, you think about relationships, but this is thinking, this is deep systems, where reality itself is a system. Reality isn't a system at the bottom, it's just arrangements of different pieces.

Thank you very much, Ruben. I have Dave Daugherty on next followed by Alan Betts and William Rees.

Now, do you want me to leave this up or take it down you could leave it up for a minute if you're going to refer to it again. We might as well leave it on, it's related to my question, Ruben, so if you'd leave it up, that'd be good.

Yeah, good afternoon and so let's make two assumptions. The first is that the current modern techno-industrial complex does not further degrade our ecosystems the second is that we can struggle our way into that indigenous area on the top right of the slide. How many people, how many humans do you think the world can support.

And that's a nice modern question, and I'm back to the place of saying modernity thinks in terms of planning, and in good planning you start with the end in mind where, here, the that we recognize the world, that in a sense, if you're going to make this journey, it helps to to as much as you can already, get into the space, and ask the questions about the journey from the space of the top right, and so every time you ask a question, you ask yourself, is that a well-formed question in the top right-hand space? Or how would that question be asked up there? And the question would be asked of, that's more about day by day learning to authentically, in other words, the top right hand space does not talk about unchanging truth. It talks about human beings and human relationships or other relationships being more or less truthful and authentic, and so what you're into is taking baby steps towards kind of growing up into that without knowing exactly how that will "turn out".

And you're willing to simply set aside the question of how many, but the question that's implicit in it, of absolutely yes, it is absolutely clear that, that the modern world cannot handle eight billion people.

And let me let me rephrase, then could we handle, could we handle more or fewer than 8 billion people if we make it into the indigenous space? My sense is that, that as modernity disintegrates, as Bill suggested in the thing that I quoted from him, Gaia, Gaia herself will deal with a lot of this question I mean my sense is over uh between now and 2000 in this century there will be hundreds of millions of in one sense needless deaths but they're not needless given the historic situation we're in, but they will be random and god-awful, and so I don't, I mean I genuinely don't know, and I think, and I wouldn't begin to say if we could all live in the top right-hand corner, that you have, because that's a question that comes out of the need to know the answer in a perfectly modern way, and one of the things that the elder indigenous elders will tell you in so far as you're thinking that way, you're thinking like a white man, and that's not what we do.

Well, but I think we've got a tough challenge to get anybody to not think like they now think, and having worked in planning and politics, so I think that's the one where we're always bumping our heads against the wall constantly.

Alan Betts has a as a question that follows well, well now, and then we'll go to Bill Rees, and to Debbie Casper, so Alan Ellen you are muted, Ellen you are still muted.

I'm now unmuted. My starting point is we really have to deal with the real world. My context for this was 50 years ago I saw disaster coming because I'm a climate scientist and I started to ask around, how do we merge science and wisdom because the mechanical view of science was clearly going to fail in relationship to the earth, and what I found along the way, quite soon in fact, I was just simply sent to India, and is that the living earth system is now consciously taking over the climate system because it's responsible for the earth and it's not doing it with respect to us. The human beings who are in charge of everything is doing it because it's responsibility, and our job is to really connect, which we can do to the living earth system and cooperate. Now, that's a radical change in perspective from we're in charge, but it is the step we have to make because it's really happening.

I couldn't agree more, it's why I use the language that we need to learn to cooperate with our own evolution.

We can do that of course, we refuse to do that, and we refuse to confront the objective, the difficulties in our society, to face it. For example, the fact that the religions dumped all the indigenous teachings are in Aramaic which are still there. You can read them and once you read them you can see it's obvious, but we refuse to confront them because they're all in charge, just as we refuse to confront our political and capitalist organizations who are content to destroy the earth for money.

If you remember the image that was there kind of, a visual image of modernity, with a big yellow square with all the pieces in it, the thing that's interesting is that within a modern techno-industrial sense, the place where there's genuine freedom is in the subjectivity of being persons, but the subjectivity of being persons counts for nothing in official space, so in official space we're just functions, not persons, but it does mean that one of the places that we can learn to cooperate with our own illusion is literally as individual persons that, just the same way Ontario has written that law recently that, that your job can only make certain demands on you if you're not at work, and that's part of modern mythology, and so there is space, and in fact you find lots of there are, there's a incredible numbers of people are learning to take more responsibility for their own life, their own aspirations, the formation of their own life in the space that modernity allows them, and bit by bit some of those people are now making that demand at work, and for me that demonstrates part of the disintegration of modernity we don't believe it like we used to, so one of the strategies I would use as a, as a formal strategy now we're advising the government of Canada today about social policy. I would say you're old enough. Allen's remember probably that in the 1970s the Trudeau government, the Pearson government had invented it. That the Trudeau government multiplied it. There were all kinds of federal grant programs, essentially for individual groups of people, there was New Horizons for older folks, there was the Company of Young Canadians, there were all kinds of community grants and others that the federal government had a strategy that by spreading all kinds of money around the place, people in small groups would be learning stuff that they needed to learn, that didn't have to be officially authorized, and my sense is, if we, what we lack is, are any leaders in the business community, and I, I mean I don't know of any. There may well be some there, but I know of no leader who's a public leader today in any institution, university president, or whatever who understands this enough to say that one of the strategies I'm going to use within my institution, so if I was a head of a corporation, 50,000 people around the world, that one of the things the HR department would do is fund people's personal growth, because without people who've gone through this to some extent themselves, who find their own voice in it, who then find other people to talk to.

It's what CACOR is about. CACOR is a community of people who have been egging each other on as they learn to do braver and braver things over the last 20 years, and it's working.

Thank you Ruben, and in fact we're going to bring Bill Rees on to respond because you've used his name in vain. It's his turn now. I'll give him the last word because we're getting that down to three o'clock. Bill, you want to have a last word, then we'll hand it over to Gene Doherty, and then we'll open it up so we can all talk off, talk offline, so that we don't end up being reported to the authorities.

Thanks very much, Ted, and thank you Ruben for just a sweeping assessment of the state of our current reality. I'm really enjoying enormously listening to you and roll once again listen.

I have a huge concern here. I think that the human mind is obsolete in the environment that we ourselves have created. The cultures we have created are obsolete in the environment that results from the creation of those cultures. Secondly, we have enormous momentum. You've several times mentioned how very few people even open the door to thinking this way, let alone entering the first room so we have a global culture. We have now another war underway which many think may unfold as the Third World War. We have absolutely no sense among industry or government or civil organizations that we need do anything, but improve our present way of being. You know what I call business as usual by alternative means, so my question is, given the enormity, enormous challenge confronting us, this transitional challenge and the apparently diminishing temporal window with climate change and, and so on, do you really have any real hope that we can survive modernity? Is there any sign whatever that anyone in position of authority or power is taking up your challenge?

Well, a quick answer to the last question, first I would never use your name in being second, your last question, no, I are our the hope is not that senior leaders are going to somehow become converts to the Bill and Ruben show, and act accordingly. I don't have any great hope for that. My experience with, and it's over most of my lifetime, with people who are deviant, it's this is about positive deviance, and how do you nurture positive deviance? And positive deviance is nurtured very personally in a community that is intellectually reliable, psychologically safe, so it's safe to learn things about yourself that are awkward and embarrassing and even at times distressing, and it's personally challenging, so those are the three criteria of the kind of communities we need to be building on small scales to do this work, because as modernity implodes, we're going to be left with, and some of those communities may then be strong enough to carry on as communities emerged in what we think of as the middle ages, the Dark Ages, when order, you know Catholic orders, began to to emerge and people gathered around an abbey, that, and had a small life for each other, so I don't have any hope that modernity can be saved from collapse. I don't have any hope that the institutions of the world will understand that and act accordingly. I think, I think therefore, the experience will be of a modernity collapsing with, our institutions collapsing as well, and the threats will be the kind of thing we have already seen, whether you're looking at Hungary or Donald Trump or Pierre Polyev or the Bill White movement, but you see people who are frightened and psychologically beyond their depth, who who unfortunately don't have any friends who are intellectually reliable, psychologically safe, and personally challenging to help them work out their anxiety with alternative understandings, so it will be a shit show to not use a other than a technical term as I talk about post-despair hope because there will be despair in degrees that we're not even imagining now.

Thank you very much, Ruben. That happy note we have definitely got a lot of questions on the panel today each of which I think could be the subject of a future debate deliberation because most of us are still here. That we wish to entertain the fact that hope exists, so, and I think that there is some in there we just have to think, and maybe that will get us there, so I will thank you personally for a very stimulating talk and the very interesting and positive and good comments and questions from others, and I would turn it over now to Gene, our president, to say thanks formally

Thank you Ted and Ruben. It is indeed my privilege, and my pleasure, to thank you on behalf of the Canadian Association for the Club of Rome. This has been again an absolutely phenomenal presentation that you've given us, both thought provoking and very provocative. I think, I think this is food for thought for so many of us, and by what I've seen on the chat line, it certainly shows that you've got people thinking, so thank you for that. For those of you who are not familiar with CACOR we are an organization, a not-for-profit organization, you are welcome to come and look at our website, canadiancore.com, you will find this particular presentation and all the other over 100 presentations that we have had since the beginning of the pandemic are available on our youtube. You can access that by looking at the stay informed section and signing up for the stadium forum section on our website. You can also find information about becoming a member of CACOR. If you're interested as well if you do go on to our youtube site, I would really strongly encourage you to subscribe to it so that you will be getting notifications for all of our things that we're doing, so again, thank you Ruben, this has just been wonderful, and with that, thank you very much.

Chat log:

14:26:34 From Thorhaug Anitra to Everyone: I have question about why scaleable regeneration cannot be built into this dynamic reality

14:30:32 From Dave Dougherty (CACOR) to Everyone: How many humans might be supported in the "indigenous" space?

14:31:20 From Alan Betts to Everyone: Living earth consciously taking over climate because responsible for the earth. Can surrender, connect and incorporate.

14:31:39 From William Rees to Everyone: Given the enormity of the transitional challenge and the apparently diminishing temporal window, do you have any real hope H. sapiens can survive modernity? Who is taking up your challenge?

14:36:03 From Debbie Kasper to Everyone: I’m with you on all of your (and Rees’) premises, and my work as a writer and teacher has always been geared toward the goals of helping people let go of MTI culture and cultivate a radically different culture. But this truly is the work of generations and we will likely not see the fruits of our efforts. What is YOUR sense of the practicalities of HOW to undertake such an enormous task?

14:38:25 From Peter MacKinnon to Everyone: Sorry I have to sign off. Thanks Ted for inviting Ruben. Thanks Ruben, good to see you. Cheers

14:53:47 From John Meyer to Everyone: Just to point out that indigenous worldviews can be very similar to those of biophysical economists but just use different language. Chief Sealth speech vs Dr. Lowdermilk - a soil expert/historian - their ethos is very similar.

14:58:38 From Zack Jacobson to Everyone: You've read "A Canticle for Leibowitz" ?

15:20:12 From William Rees to Everyone: Brilliant, Ruben. Thank you. Gotta go.

15:21:28 From Thorhaug Anitra to Everyone: Very profound which should inform us. Excellently expressed. Thank you, Ruben.